Buying “New-Space-Smart”: Space Acquisition Advice for the Biden Administration

Summary

We are no longer waiting for the arrival of a New Space Era. It is already here.

The many changes brought by this New Space era are affecting governments worldwide and all sectors of the commercial space industry, but perhaps the greatest impact is on the US Government.

As the Biden Administration enters office in January, it will need to confront the fact that America’s once dominant and uncontested space leadership position has been eroding for years.

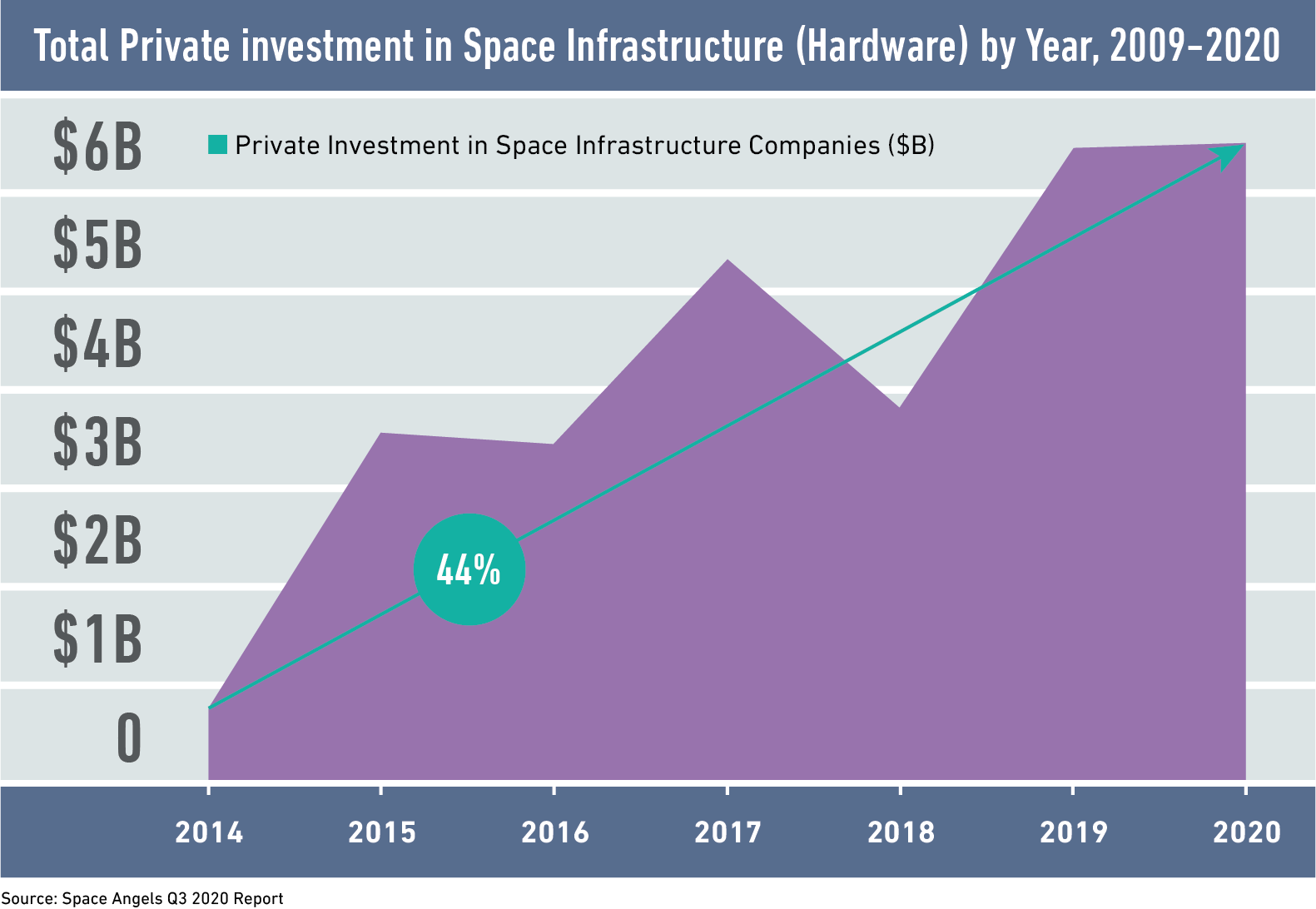

As America has begun to address these major changes, space budgets have increased in recent years with a focus on improving situational awareness, resiliency, defensive and counter-space capabilities, and space exploration and science.

But clearly more needs to be done, and fast. That’s why the US Government must adapt quickly as new threats and mission needs arise across all aspects of its space enterprise:

- Civil,

- Defense, and

- the Intelligence Community

The Biden Administration’s new space leaders have a lot on their plate. To better understand the real-world dynamics of government space innovation and acquisition, and to generate ideas to help guide future space R&D and acquisition plans, Avascent worked with three former senior US space officials.

ROBERT CARDILLO

Former NGA Director

LORI GARVER

Former NASA Deputy Administrator

DEBORAH JAMES

Former Secretary of the Air Force

The good news is that, in many ways, the US Government has already begun to respond well to its new space challenges:

- The Department of Defense has adapted its space acquisition and governance structures (standing up the new US Space Force and Space Development Agency) and

- NASA and the Intelligence Community have used more creative contract mechanisms to acquire commercial services (NASA’s acquisition of “services” in its Commercial Crew and Cargo programs; NGA and NRO’s commercial purchases of space imagery).

However, most US Government space programs remain expensive, slow to deploy and vulnerable to both kinetic threats from adversaries and technology obsolescence.

Moreover, the ongoing pandemic crisis and its aftermath will undoubtedly create new budgetary challenges, putting increased pressure on space innovation and acquisition.

Below we share some perspective from those conversations on how the new Administration can learn from the past to better navigate space challenges.

Key Space Acquisition Challenges

1. Integrating Innovation – Bridging the ‘Space Valley of Death’

It is always hard for governments to deploy innovative concepts and technologies at large scale.

US Government rules, oversight and procedures create friction at every step of the innovation process; moving great new technology into “programs of record” can take many years – time that we may no longer have.

The “valley of death” between innovative research and development and usefully-deployed capability has been a problem across the US Government for years, and is just as true for space programs as it is for military aircraft or fighting vehicles.

The Space “Valley of Death”

The Space “Valley of Death”

Both the US Government and the private sector have been interested in deploying new constellations of satellites into low earth orbit (LEO) for years.

In 2015, the US Missile Defense Agency initiated an analysis of how to use space-based sensors to track conventional and hypersonic missiles.

Around the same time, SpaceX announced that it was considering deploying Starlink, a large constellation of communications satellites.

Five years later—and with no satellites launched—Congress is still debating which organization should lead LEO deployments. Conversely, SpaceX has now launched over 800 operational Starlink satellites (with broadband speeds over 100Mbps), has developed and sold hundreds of ground terminals, and has announced business deals with major customers, including Microsoft.

Photo Credit: OneWeb

2. Re-Balancing Risk

The US Government developed an acquisition model for space that prioritized safety, reliance and mission assurance (i.e., lowest technical risk) over speed and cost (i.e., schedule and budget risk).

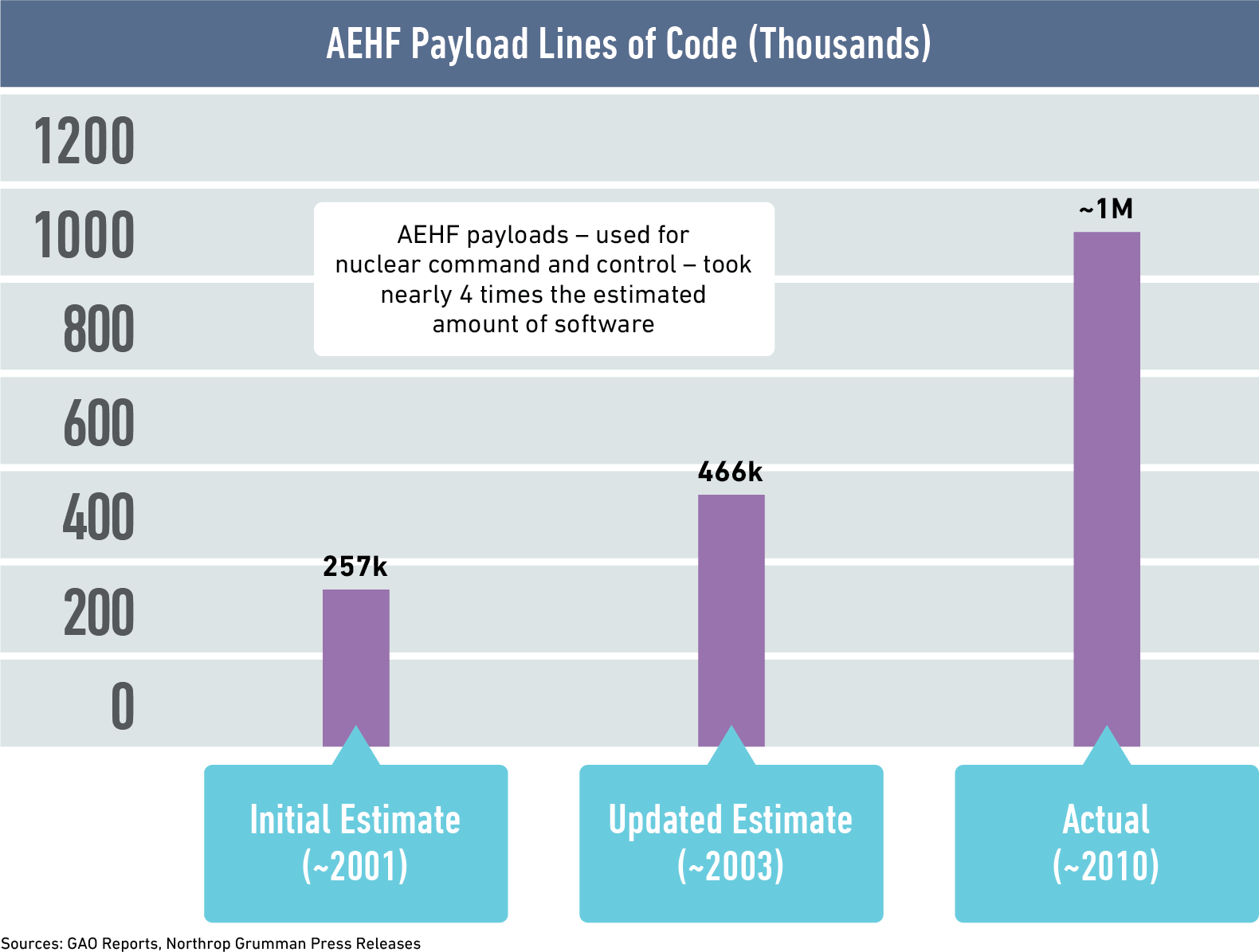

This model can work very well, as with the highly successful GPS constellation that underpins so much of the world’s economy. But it can also result in multi-year delays and billion-dollar-plus cost overruns, for example with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and the Air Force’s AEHF satellite network.

To succeed in an era of contested space and constrained budgets, the USG will need to re-balance schedule and budget risk with technical risk in every space acquisition.

Does the government need the “perfect” capability at the lowest risk (and the costs and schedules that go with that), or is there a “good enough” option which can be deployed faster and cheaper?

3. “Space Software – Harder Than Rocket Science?”

The engineering and physics required to control the millions of pounds of thrust created by rocket engines and manage 3,500-degree-temperatures in atmospheric re-entry are truly hard technical parts of space.

Yet the “invisible” digital aspects of space technology often are just as challenging, or more so, in this New Space era.

For example, poorly developed and inadequately tested software code caused a near-catastrophic failure during the Boeing Starliner astronaut vehicle test flight for NASA earlier this year; and software development problems have cost the Air Force years of delay (and billons in cost overruns) on its new GPS ground network, OCX (see case study below).

Whether used for NASA’s deep space exploration, the NRO and NGA’s sensing and analytics, or software-defined payloads for Space Force communications satellites, the role of software will only grow.

Managing the software innovation and complexity of the New Space era will require the US Government to continue to break down bureaucratic barriers and old habits of acquisition and testing to ensure space needs are met on time and on budget.

This means putting the right people in the right jobs, empowering them to make good decisions, and rewarding those calculated risks.

Learning from the Past for a Wiser Space Acquisition Future

Deborah James, Robert Cardillo and Lori Garver all agreed that the Biden Administration must use the lessons learned from our space acquisition past to help chart a wiser course for the future. As current and new space leaders grapple with institutional, technological, and budgetary constraints, three main lessons point toward a smoother, more efficient and New-Space-friendly acquisition future.

1. More Commercial Sourcing, More Often

The Biden Administration must better harness commercial space capabilities and innovation expanding upon recent successes at NASA, especially, at the NGA and NRO, and most-recently in the DoD.

NGA/NRO Imagery

NGA/NRO Imagery

Robert Cardillo noted how commercial capabilities changed the thinking of the intelligence community about space sensing.

One of the key challenges faced by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency in the early 2010s was the proliferation of high-quality commercially owned space-based Earth sensing capability.

This was a big deal for a “closed” Intelligence Community that was used to relying exclusively on its own assets and analysis, Cardillo explains. “The real introduction of commercial imagery was one of the biggest challenges [NGA/NRO] faced this past decade.”

Starting with the large NextView / EnhancedView contracts with Digital Globe, then expanding commercial sourcing through contracts with Planet and other commercial companies, the NGA and now NRO have sought to open their architecture, increasingly drawing upon commercial innovation.

“For a long time it was a closed system, only [government-owned] classified input leading to classified, closed output, even while the world became more open and transparent,” reminding us that space acquisition authorities need to improve their agility in harnessing commercial innovation.

Photo Credit: BlackSky

Looking to the future, the NRO and the NGA must continue their initiatives to diverse imagery sourcing and analytics from commercial providers.

DoD’s initiatives, including the still-unproven Space Development Agency and Space RCO, will be critical to determining whether and how the Space Force stand-up accelerates use of commercial capabilities, or if it defaults back the pre-Space Force habits.

NASA continues to lead the way in utilization of commercially-adapted capabilities, as it applies lessons from its Commercial Crew and Cargo acquisition models to its Moon-to-Mars Artemis programs.

For example, its Commercial Lunar Landing Programs (CLPS) that is buying Moon landings “as a service” from more than a dozen qualified providers.

was one of the biggest challenges

[NGA/NRO] faced this past decade.”

– Robert Cardillo

2. "Good Enough” Outcomes Over “Perfect” Capabilities

Military and civil space organizations have long prioritized an acquisition strategy for specific, highly prescribed space capabilities and assets.

Traditional space procurement processes rely on government entities to design, develop and oversee the building, testing, deployment and operations of space assets.

Government contractors in turn respond to these highly specific needs and build what is asked of them, down to the last detailed requirements, changing production plans and schedule (and increasing cost) as the government customer amends its requirements.

Moreover, these space assets are often bought separately under discrete programs. Not surprisingly, these programs don’t always align: satellites wait in storage for launch vehicles to be ready, or vice versa, and then once on-orbit, satellites can wait months or years for ground systems to come online.

NASA Commercial Crew and Cargo Programs

NASA Commercial Crew and Cargo Programs

The traditional space acquisition model can still be best in many cases but is less effective in others.

The concept of leveraging the private sector for International Space Station transportation was first envisioned decades ago at NASA under the leadership of Administrator Dan Goldin.

Several early programs were seeded in the 1990s with a goal to “turn over the keys to low earth orbit.”

Administrator Mike Griffin developed the concept further by creating the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program in 2006 and the Obama Administration initiated a formal commercial crew program in 2009.

Purchasing outcome-based “services” from commercial companies instead of buying assets and integrating them within NASA, as it had with Apollo and the Space Shuttle, allowed the government to take advantage of advances in private sector capabilities to grow non-government markets and reduce costs to tax-payers.

NASA has awarded contracts to SpaceX, Boeing, Orbital Sciences (now Northrop Grumman) and Sierra Nevada to deliver cargo and now astronaut transport “missions” commercially, overseen but not operated by NASA.

While this has proven successful, changing the acquisition model for something as important as astronaut travel was not simple, Lori Garver explains. “Transporting astronauts to and from ISS was seen as a government responsibility and there was a natural reluctance to make changes that could increase risks.”

Launching satellites was already a commercial endeavor, but having a single US operator had eliminated commercial competition and driven up costs significantly.

The first acquisition under the new construct, the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program to the space station, was awarded for cargo only and viewed as a low-cost and low-risk way to incent a more competitive industry.

When problems were uncovered with the vehicle being developed to replace the Space Shuttle, it was determined that private sector capability was also sufficiently mature to develop crew transportation with less government oversight.

“Determining which programs are best suited for different acquisition models requires detailed assessment of technology readiness, opportunity for innovation, potential for leverage of non-government markets and of private sector capabilities and interest.”

The successful service-based procurement paradigm that guides Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) missions and the Commercial Crew Program that has already led to SpaceX’s May and November 2020 successful missions to the International Space Station has saved the tax-payers more than $20 billion dollars because it was a mature technology with a robust potential market and significant private sector capability and interest.

Photo Credit: NASA

Upcoming Human Landing System (HLS) awards are expected to continue pushing us towards an outcome-centric approach to acquisition. Although Garver warns us that “while this worked well, it shouldn’t be a cookie cutter approach.”

Space acquisition authorities ought to critically ask themselves whether and how this type of procurement architecture would leverage competitive dynamics to achieve agility and cost benefits that help them execute their critical missions.

3. Embrace Digital Complexity – and Digital Talent...

The challenges brought on from the increasing software complexity in the launch systems, ground infrastructure, spacecraft, and space robotics must be better-addressed in next-generation space acquisition.

Often delays and hurdles start at the very onset of a program, as requirements, schedules and testing regimens are established, but are sometimes divorced from the realities of delivery.

Software is increasingly part of the biggest challenge. For example, the US Air Force’s AEHF’s payload was originally estimated to need ~257,000 lines of software code – just one quarter of the 1 million lines that were actually required.

Now, on AEHF’s successor, Evolved Strategic SATCOM (ESS), currently under a study contract, the government should put software complexity front-and-center to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past

The GPS Ground System (OCX)

The GPS Ground System (OCX)

As the Air Force deployed its next generation GPS satellites, it also designed a new GPS Ground Network: The Operational Control System (OCX).

This was a major effort, as it had to control and integrate with all legacy GPS satellites and capabilities, as well as the next-generations system.

Deborah James, Secretary of the Air Force, was front and center in dealing with the problems of OCX acquisition and deployment.

Navigating the OCX program, “the government handed out poor requirements, and then proceeded to change them often,” says Secretary James. “Sometimes in government the quest for perfection by procurement officials means that good-enough suggestions are held up.”

One of the key challenges on programs with significant digital components is that at times leaders with limited software program management qualifications remain in charge, or they don’t know where to reach within their own organizations.

There are two priorities she sees: “Make sure that software-smart talent is in the room for big decisions – this may mean having staff in torn jeans and t-shirts at the table with leaders in nice suits and uniforms.”

Secretary James also added it is critical to “get the right leaders in and don’t be afraid to swap them out, but keep good procurement managers in for longer terms of service, rotating less.”

To do this, acquisition authorities must rely on the right kind of people. “We need to educate our acquisition workforce better. Senior leaders say a lot, but the rubber ultimately needs to hit the road with execution staff.”

Similar to comments made by Lori Garver about NASA, she adds: “People need to believe they are not going to be penalized for taking risk when appropriate.”

Photo Credit: Raytheon

While recognizing and prioritizing software complexity in space acquisition is critical, perhaps the government’s biggest challenge is establishing digital literacy among its workforce.

Proficiency with the digital elements of space is going to be an increasingly important requisite for our acquisition workforces, and the government will need to prioritize hiring software engineers as much as it does mechanical, electrical and systems engineers.

People with the right skillsets both in the government and among commercial partners and suppliers need to be empowered to manage the digital complexity of space and to do it on time and on budget. This will require rethinking hiring of staff, training, and prioritizing software knowledge over seniority or titles.

the room for big decisions – this may mean

having staff in torn jeans and t-shirts at the

table with leaders in nice suits and uniforms.”

– Deborah James

Concluding Questions for the New Biden Administration

Secretary James, Director Cardillo and Deputy Administrator Garver stressed that the incoming Biden Administration will need to accelerate the current momentum in adapting US Government space acquisition to the New Space era. The most critical changes and underlying questions must include:

More Commercial Space, More Quickly

The USG must require that readily-available “commercial” capabilities be incorporated into USG space acquisition more often, ensuring that innovative technology gets used quickly, as opposed to designing and re-designing architectures over years and decades.

- Are the right (or any) guidelines in place for rapidly identifying which missions stand to benefit from commercial cost/speed and can they accept the associated risk?

- Who is in charge of monitoring commercial capabilities to ensure they are considered and well-understood in mission and acquisition design?

- Are flexible contract mechanisms to bring in commercial capabilities (e.g., OTAs) being used to maximum effect?

Buy Space Outcomes, Not Just Technologies

Encouraging (and championing successes of) acquiring mission outcomes, e.g., building off and learning from the ongoing success of NASA Commercial Crew and Cargo programs.

- Are the desired program and mission outcomes clear to all acquisition staff?

- Is there a requirement to consider the viability of outcome-based acquisition in every acquisition? Who is in charge of the assessment?

- What is the optimal way to structure and incentivize outcome-based procurements and contracts?

Add Digital Talent for the New ‘‘Digital Rocket Science”

Re-align, re-train and creatively hire digitally-oriented, software-familiar staff for Government space acquisition and oversight teams, incorporating more commercially-experienced talent, especially software engineers.

- Can the US Government compete for the digital talent it needs in space acquisition?

- Do USG customers have the right organizational structure in place to on-board and integrate non-traditional/commercial talent?

- Can OPM pilot a broader government experiment whereby government and industry can exchange talent on a periodic basis?

- Does the government have the flexibility to deploy non-traditional staff most effectively on space acquisitions?