2020 MSPO Previews: Defense in the Time of the Coronavirus Pandemic

Between Aspirations and Reality in the Execution of the Defense Modernization Agenda under the Limitations of the Pandemic

This year’s edition of the International Defense Industry Exhibition ‘MSPO’ in Kielce, if it is able to take place according to plan, will be the biggest defense-orientated trade event in Europe with in-person meeting opportunities.

Although the organizers do not expect another record-level of attendance due to the overall epidemiologic situation, nevertheless the organization and healthy execution of the event will be seen as a success by itself.

The exhibition is taking place just after the centenary anniversary of the Battle of Warsaw, one of the top twenty most important battles in history, which saved Poland and Western Europe from Soviet invasion in 1920.

From a strategic point of view, today’s situation in Poland is completely different than it was a century ago. At that time, the newly reborn country, which had regained sovereignty only in 1918 after a hundred and twenty-three years of occupation under a partition between Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

This new nation had to fight with Soviet Russia with almost no ally support and almost no indigenous defense industrial capabilities.

Today, Poland is a member of both the EU and NATO, with firm ties with the United States[1] and up to about 5,500 strong US troops present on the ground.

Poland is an active regional player, an advocate of the Three Seas[2] Initiative, it fulfills its NATO’s objective to spend 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) on defense and has an ambitious defense modernization agenda.

advocate of the Three Seas Initiative, it

fulfills its NATO’s objective to spend 2% of

gross domestic product (GDP) on defense

and has an ambitious defense modernization

agenda. "

However, its location on the Eastern flank of NATO combined with Russia’s on-going military build-up, destabilizing activities in Ukraine, and the intense situation in Belarus create a regional security environment that is very challenging.

Additionally, President Trump’s decision to shift nearly 12,000 troops out of Germany may also negatively impact the efforts focused on the enhancement of the deterrence measures against Russia.

On top of that, China is a growing player in the region. Poland is a vital country for the Chinese strategic One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. Since 2011, cargo trains have been delivering goods through the Silk Road Railway from China through Poland to Germany and Western Europe.

The OBOR project, combined with 5G infrastructure, may also have a substantial strategic dimension to further strengthen China’s position and the competitiveness of Chinese entities on the global market.

In this already complex environment, the pandemic brought a new unknown factor whose final consequences, including a potential second wave, are very hard to predict. Nevertheless, with 67,372 cases of COVID-19 reported by the end of August, Poland has been handling the pandemic relatively well so far.

COVID-19 and Financial Implications

Poland entered the pandemic with a balanced state budget and an overall healthy financial situation which allowed for manoeuvre during the first critical weeks of struggle against COVID-19.

Although the final impact of the pandemic on the economy is still unknown, it is predicted that GDP will shrink between 4 and 5% in 2020, which is a relatively minor drop compared to other European countries more harshly impacted by COVID-19. In the following year, the GDP should jump up by about 4%.

However, it is also worth mentioning that in the upcoming years, in addition to COVID-19 burdens, the Polish economy will struggle with a slowing GDP. According to the Ministry of Finance’s forecast,[3] the GDP growth will steadily decrease to below 3% in 2029.

The trend will continue in the following years. The EU funds within the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MMF) 2021-2027 may temporarily provide an additional boost to the economy but does not resolve the structural challenges Poland faces, such as unfavorable demographic trends or an under-financed and unreformed healthcare system.

Poland is one of the fastest aging societies within the European Union. This causes growing budget pressure from the pension system and the social assistance system.

The drop in GDP growth will negatively impact the defense budget. Due to the complex nature of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the precise scope of economic shock is unknown.

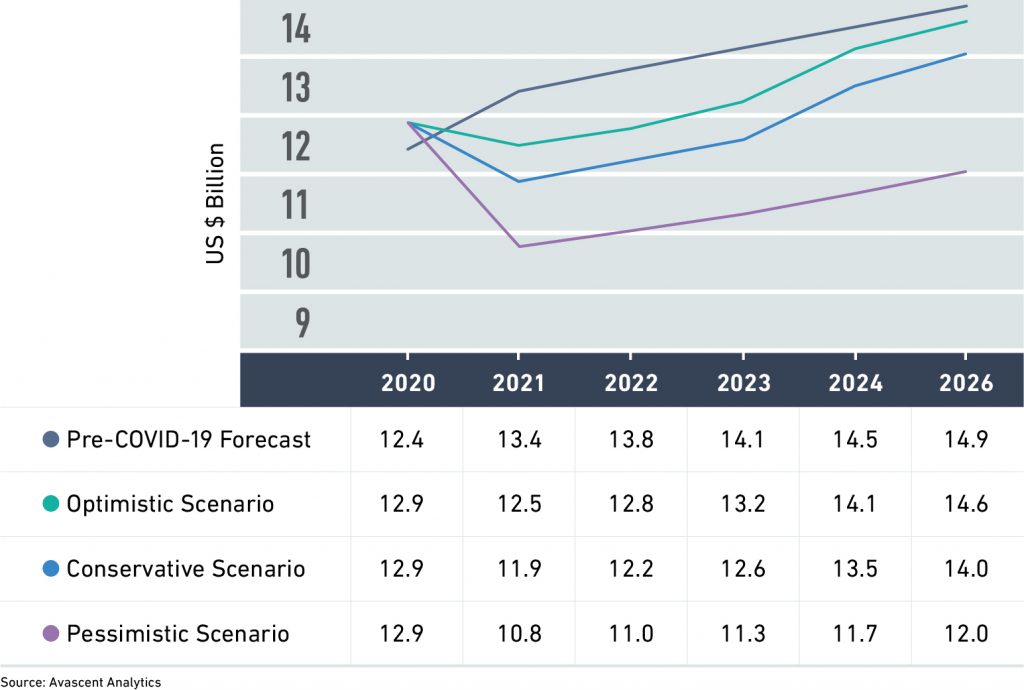

Therefore, it seems appropriate to envision a series of scenarios for how defense spending may differ from pre-COVID-19 expectations. In this regard, figure 1 is an initial Avascent estimate of three scenarios for how Poland may see defense spending reductions in the midterm.

Figure 1: Poland Defense Spending Scenarios 2020-2025

Cumulative defense spending, which according to the pre-COVID-19 forecast should reach $83.0 billion by 2025, may decrease by $2.9 billion in an optimistic scenario, through $5.9 billion in a conservative outcome to even $13.3 billion in the most adverse scenario.

The allocation on defense investment, typically regarded as procurement and development activities, will also be trimmed.

Assuming that a quarter of the defense budget is allocated towards procurement, the cumulative defense investment gap may reach from $0.7 billion in an optimistic scenario to $1.5 billion in a conservative scenario, and up to $3.3 billion in a pessimistic one.

Overly Ambitious Defense Agenda

The gap in defense spending will have consequences for the scope and pace of the defense modernization agenda.

To meet the military’s extensive modernization requirements, Poland has planned to increase its defense spending from 2.1% of GDP in 2020 to 2.5% of GDP by 2030 although President Andrzej Duda encouraged the government to reach this goal as soon as 2024.

The new Technical Modernization Plan (TMP) 2021-2035, which was announced in 2019, covers about 2,000 modernization programs. According to the Ministry of National Defense’s (MND) declarations, about $133 billion will be allocated via TMP implementation by 2035.

However, the implementation of such an ambitious agenda seems to be challenging in the coming years. Setting aside the feasibility of GDP growth on defense (which is in question due to GDP drop, pandemic burden, healthcare, and welfare costs), the lesson from the implementation of TMP 2013-2022 is not very encouraging.

So far, the MND has procured comparatively small quantities of modern weapon systems relative to the vast modernization requirements. Poland procured thirty-two F-35A combat aircraft under the Harpia program, just two out of eight planned mid-range air and missile defense batteries within the Wisla program, one out of three divisions of rocket artillery systems under the Homar program, and mere eight (four S-70i Black Hawk and four AW101) out of about 100 required helicopters.

Additionally, the overcomplicated and inefficient defense procurement system, which badly needs comprehensive reform, will not make the case easier and has not shown signs of improvement.

On top of that, the pandemic adds an additional, high-risk factor into the implementation of an already complex modernization agenda. However, COVID-19 also provides a good excuse for decision-makers to review and transform the defense wish list into a realistic and executable plan of objectives in terms of defense modernization and the final shape of the armed forces.

Consequently, the MND should focus in the mid-term on a few urgent capability gaps such as space and drone ISR, SHORAD and mid-range air defense systems, and on the restoration of naval surface and submerge capabilities.

urgent capability gaps such as space and drone ISR,

SHORAD and mid-range air defense systems, and

on the restoration of naval surface and submerge

capabilities. "

It would also be reasonable to rethink the plans on the final size of the army. Due to challenges to national security, the MND decided to double the size of the armed forces to 200,000 soldiers and is in the process of forming a new mechanized division.

However, doubling the size of the armed forces, if even feasible, will lead to substantially higher spending on military personnel, infrastructure, and operational and maintenance outlays.

These risks cutting into spending allocated to hardware procurement. From an operational and capability point of view, a slimmer but more technically advanced armed forces would be more efficient on the battlefield than a large but technically vintage army.

In this context, it is also worth mentioning that, as part of a new security cooperation agreement with the US, the MND will also have to pay the cost of the US troops presence, which is initially estimated to be at least $125 million annually.

Therefore, the allocation of limited MND’s financial resources should be very carefully contemplated to achieve the best cost/effect ratio.

Last Opportunity for the Reform of the Polish Defense Industry

The government constantly declares that one of the key goals is the development of sovereign defense industrial capabilities and the integration of the local providers into the supply chains of global defense contractors. However, the implementation of that goal in practice has been rather moderate so far.

This is a peculiar situation considering that the MND has allocated a substantial amount of money on defense investment, but the local, mainly state-owned, defense sector is still largely unreformed with no substantial export successes.

Furthermore, the downturn due to the pandemic has the potential to accelerate a reshaping of the global defense industry ecosystem. Therefore, it is imperative that the Polish MND and the Ministry of State Assets understand their goals for the Polish defense industry and its current place on the global map.

The government, together with the defense sector, could proactively embrace the challenge by providing an emergency plan tailored for the defense sector following the French or Spanish solutions to rebuild and prepare the sector for the post-COVID-19 world.

However, so far, the sector can only apply for the instruments dedicated to other sectors of the economy within the so-called Anti-crisis Shield[4]. The time is running out to adapt the sector to a new environment and the market challenges these firms face.

Race Against the Clock

The pandemic itself brought a totally new risk factor to an already complex defense and security environment in Poland. Officials must make decisions to both fight against the pandemic and continue to implement a vast defense modernization agenda while keeping in mind the decreasing GDP growth and very unfavorable demographic trends.

Today’s decisions will determine the military potential of the nation’s armed forces and the capabilities of the local defense industry for the next decades. It is likely that the impact of COVID-19 on Poland’s defense spending will take the form of some spending cuts and budget reallocations to fulfill social and healthcare priorities.

Additionally, it is expected to grow spending on operational and maintenance and military personnel, therefore, it seems safe to assume that Poland will continue to invest in military hardware but at a slower pace in the midterm.

Footnotes:

[1] The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) was signed 15 of August 2020.

[2] The Three Seas Initiative gathers twelve countries in central Europe between the Baltic Sea, the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea. The initiative is a forum focused on both political dialogue and energy and infrastructure projects.

[3] Guidelines on the macroeconomic indicators, July 2020.

[4] The Polish government allocated $82 billion on emergency measures to keep running the national economy.