Defense Spending and COVID-19: Implications On Government Finance and National Security

COVID-19 has grown into what many observers saw as a worst-case scenario during the SARS (2002), MERS (2012) and Ebola (2014) outbreaks of recent memory.

As deadly as those epidemics were, they affected economies less than the most dire forecasts of the time. These outbreaks had limited effects on underlying economies and government expenditures. From the standpoint of global military spending and defense suppliers, the effects of these episodes were minimal compared with sectors like commercial aviation.

When COVID-19 was first detected in late 2019, it was briefly relegated to a second-tier news story in the West, seen as a crisis confined to a single provincial Chinese city. But it is clear now that COVID-19 will have extremely deep effects on global economies, employment, and government finances.

Combined with the concurrent plunge in oil prices stemming from disputes between Russia and Saudi Arabia, the current crisis has the potential to be one of the most wrenching events to affect global economics and government finance in decades.

Around the world, governments are struggling to account for a radically altered state of public finance. Saudi Arabia announced on March 20th it will double its debt ceiling to 50 percent of its GDP, whilst Italy expects to see its GDP decline by at least 6 percent.

In Spain, some predict GDP will shrink by 15 percent for calendar year 2020. The United States faces similar economic pressure, with the Congressional Budget Office forecasting a 7 percent decline in Q2 amidst rising unemployment.

The combination of the pandemic, the economic impact of quarantine measures needed to contain it, and the concurrent oil price war have put the defense ecosystem under strain in entirely new ways and to unheard of depths of severity.

In nearly every facet of supply and demand, the defense marketplace is being upended around the world. In many countries, armed forces are being used to back up healthcare, logistics and domestic security services on a 24/7 basis.

These operations will trigger a near-term increase in operations and maintenance (O&M) and military personnel spending.

Beyond their role in supporting public health efforts, the recent fate of the US aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt, which was forced to curtail its deployment in response to an outbreak among its crew, highlights the direct strain – and the costs – that the rapidly spreading virus is putting on operating forces.

A key question for defense planners and executives among defense firms is what the immediate and enduring repercussions will be on defense spending from this crisis?

At a time when threat perceptions continue to rise, the economics underpinning robust defense expenditure are entering a period of almost unprecedented strain. How will governments adjust to these new conditions, in which their financial resources are stretched to the breaking point, even as the need to support workforces, companies and military services grows in ways few observers ever imagined?

This white paper represents an effort by Avascent to address these questions. Avascent Analytics, a unit of the global consulting firm Avascent, analyzes supply and demand trends in the global defense market.

Our team helps clients in government and industry understand how defense markets are shaped by strategic, economic, political, and institutional forces. This paper is the first in a series that will explore how the COVID-19 crisis will impact defense markets.

Factors to Weigh in Forecasting Defense Expenditure

Avascent has begun to develop a framework to think about how defense spending may shift among countries with substantial military expenditures, particularly those that comprise the bulk of the western-accessible defense market.

It should be clear at this point that the situation is still very fluid and forecasting a single outcome is folly. For this reason, this paper will outline the key factors Avascent regards as likely to shape defense spending – and particularly defense acquisition spending – in the near- to mid-term. In coming editions of this series, our team will elaborate a range of estimates.

A critical input for these estimates is the level of economic growth in GDP that individual countries are likely to see in the near- and mid-term. As noted above, many countries and financial institutions around the world are scrambling to assess how deep and how long the impending global recession will affect various countries be.

Current estimates range from a short downturn with a recovery beginning in the second half of 2020 and others that foresee a downturn lasting into 2021. This uncertainty is another reason why Avascent will generate a range of potential outcomes.

To estimate future propensity to spend on defense modernization, it is critical to gauge a series of considerations, spanning economic, political, and strategic considerations.

Figure 1: Key Factors Shaping Decisions on Defense Spending Levels and Allocation

Economics

- Decline in tax receipts and government spending

- Ability to engage in deficit spending

- Impact of currency exchange rates

- Other sources of revenue (oil sales, foreign assistance)

Politics

- Defense vs. other public goods: Healthcare, Public safety, Income support, Economic stimulus

- Defense costs involving domestic spending vs. imported sources of supplies, equipment & services

Strategy

- Underlying threat perceptions

- Balance among force size, readiness, modernization

- Defense industrial base considerations

- Alliance obligations

Economic Growth:

GDP is a useful (if incomplete) metric for gauging a country’s expenditure on defense. A rise or fall in overall economic activity is a reasonable proxy for a central government’s tax revenue, and thus its wherewithal to spend on various public needs, including defense.

A country’s share of GDP spent on defense has come to be a widespread metric for judging a country’s prioritization of national defense versus other priorities.

The NATO alliance uses share of GDP spent on defense as a key metric for military preparedness among member states. The official NATO objective of 2 percent is, of course, a standard that has caused great friction between the United States and many of its allies.

To be sure, estimating countries’ military spending purely on the basis of the percentage of GDP allocated to defense is potentially problematic. For many countries, there simply is not a fixed linkage between growth or decline in GDP and expenditure on defense.

Many countries have the wherewithal to supplement normal revenue flows in times of economic downturn, either via extended deficit spending or with other means (e.g., oil revenue).

In a period of very low interest rates, the former maybe highly appealing in those countries benefitting from the financial flight to quality. Some of these measures are likely to be used in the impending COVID-19 crisis.

But as we will discuss below, a decision to draw on these measures will be taken in light of competing demands for government funding, which will be substantial.

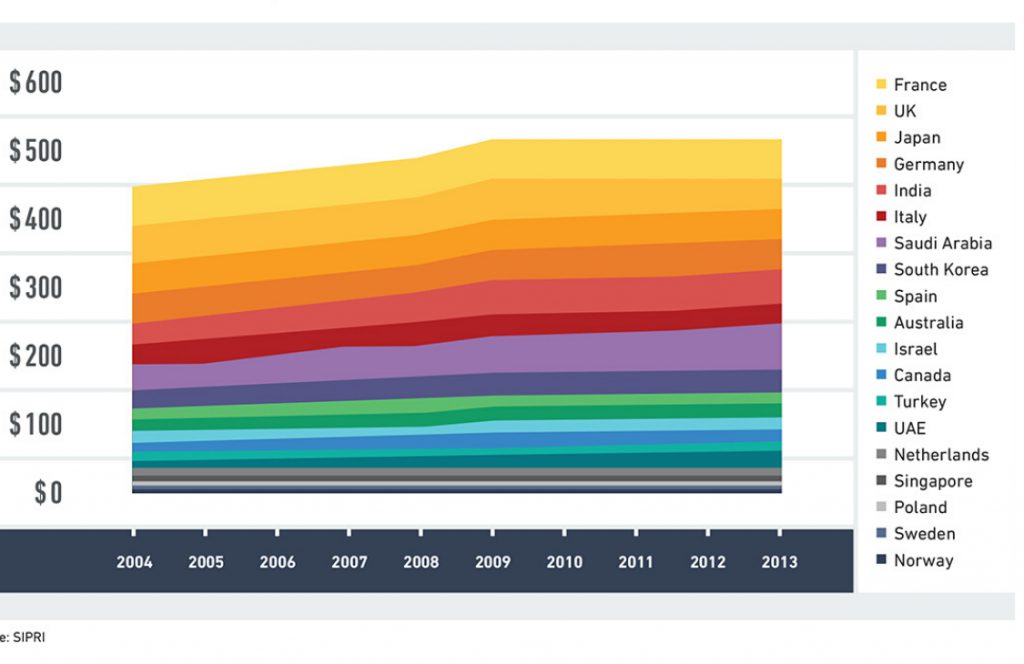

As figure 2 shows below, a serious enough economic shock can have drastic effects on defense spending. The 2008-09 global financial crisis had the effect of flattening what had been a period of significant growth in global defense spending.

In many countries, the share of GDP spent on defense actually increased during and immediately following 2009. But real growth in spending came to a halt in many countries.

Figure 2: Defense Spending Among Selected Countries Before and After the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis (Constant 2018 US Dollars in Billions)

Currency Exchange Rates:

Many countries will see their purchasing power eroded as their local currency depreciates against the US dollar or other global reference currencies.

This effect will be particularly insidious for defense investment accounts, where substantial materiel may be imported from abroad. But it will also affect more workaday expenses involving goods or services acquired from outside a country’s borders, such as:

- Fuel,

- Foodstuffs, or

- The nearly infinite variety of supplies and equipment needed to operate even a basic military force

Oil Prices:

Were it not for the COVID-19 pandemic, the recent plunge in global oil prices would be a bigger front-page story around the world. Assuming its holds, this trend will mix with broader economic dislocation in various ways.

Middle Eastern and Persian Gulf countries are obviously highly dependent on revenue from oil & gas to support government spending, including on defense.

Saudi Arabia and UAE have been not only critical buyers of defense equipment, but also have helped to subsidize the purchases of other Arab states, including Egypt.

Oil prices – which in March reached their lowest point in over 20 years – also affect the economies of other countries in the global defense market, including the United States, Canada, and Norway.

For many defense customers, including the US Department of Defense, which spent over $9.6 billion on petroleum products in fiscal year 2018, an extended trough in oil prices will relieve some pressure on operations & maintenance budgets.

Competing Demands on the Public Purse: Given the dire health and economic conditions we are seeing in 2020, there is a good chance that concern for military preparedness will rank low among the priorities of many governments in the near-term. The cost of providing health care, income security, and economic stimulus will increase as a share of public spending in many countries.

We have already seen this effect start to unfold. Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš announced on the 17th of March that military acquisitions are under threat by austerity measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the $2 billion Infantry Fighting Vehicles program, stating that “today we probably do not need the IFVs, but we need other things for this war.”

Similarly, the Spanish budget has already been impacted by months of prorogated funding, and governmental crisis has led to key program cancellations even prior to COVID-19. Given the devastating impact of the virus in Spain it is expected that further cuts are highly likely and will disrupt the modernization and life extension programs currently underway.

Among countries that have experienced truly severe impacts from COVID-19 – either in mortality or in economic contraction – Avascent may assume a correspondingly strong shift from defense to other spending.

As noted above, where countries can draw on deficit spending, they may partly blunt the impact on defense or other discretionary accounts. To the extent that interest rates begin to rise in the near-term, however, this path will become untenable for many countries.

widen a separation between the US & European

defense industrial bases & supply chains."

Strategic Considerations and Threat Perceptions:

Many countries that make up the bulk of the global defense market do not have the luxury of sidelining defense spending in favor of public health and economic support.

In its development of forward-looking defense spending scenarios, Avascent has been grouping countries in part on the basis of their proximity to potentially hostile neighbors. India, Israel, Poland, South Korea, Turkey and others loom large in this regard. These countries will try to protect defense spending against serious reductions to pay for other public costs.

Beyond simple geography, other considerations play into threat perceptions and a willingness to protect defense spending from cuts. The United States, particularly, but also France and the United Kingdom, sustain varying degrees of forward-based military posture and high operating tempo.

These are difficult to draw down rapidly. And while the COVID-19 outbreak began in China, and that country will sustain economic costs like all others, it seems feasible that Beijing will emerge from this crisis relatively stronger than its adversaries.

This could heighten the US and some other countries’ resolve to avoid deep cuts in defense spending.

Defense Budget Allocation:

How countries allocate reductions in topline defense budgets to personnel, operating, and investment costs will also vary. As noted above, many countries will rely on their military forces to assist with domestic health care, logistics and security operations.

We are likely to see a near-term increase in military personnel and operating budgets for these reasons. Indeed, making rapid cuts in costs related to personnel and operating forces can be difficult. By contrast, defense modernization funding often looms as the pool of funding most amenable to reprioritization and delay.

While these steps are undesirable and can yield serious complications in terms of long-term growth in costs and an erosion in military capability and readiness, they can be hard to avoid in the crush of near-term priorities.

Having said that, in a period of sudden and deep unemployment, many countries could look to protect parts of their materiel acquisition budgets in order to sustain domestic manufacturing and associated jobs.

This could shape decisions about which programs proceed and which get shoved to the back burner. Shifts in exchange rates among global currencies could also have an important impact on national decisions on defense investment priority.

For many countries around the world, defense transactions denominated in US dollars will seem steeply more expensive than they would have just a few months ago. The temptation to prioritize contracts in local currencies could further trump long-term capability requirements in near-term decision making.

While it is too early to tell, the aftereffects of the COVID-19 crisis could widen a separation between the US and European defense industrial bases and supply chains.

Initial Impressions of Defense Spending Impact

The Avascent Analytics team is developing a framework based on these concepts for forecasting a range of outcomes for the depth of impact on defense spending. These vary in severity, based mainly on the degree to which economic conditions decline in the coming years.

The most pessimistic scenarios estimate a worst-case set of conditions that could emerge as countries register spiraling costs for health care and social support amid deepening job losses (almost 900,000 in Spain as of early April).

Under these scenarios, governments will be forced to make progressively more severe reallocations of public finances from defense to other purposes in light of the terrible ripple effect of COVID-19.

To provide some sense of scale, our initial estimate for defense spending cuts in Europe[1] range between $20.6 to $55.9 billion in 2020, depending on the scenario.

This represents a reduction of between 7.8 percent and 21.1 percent of previous estimates, which assumed that European countries would spend $265.4 billion on defense in 2020.

In even our most optimistic scenarios, COVID-19 seems highly likely to trigger a suspension in the recent trend of defense spending growth in Europe.

The scale of European (and Canadian) spending on defense has been a source of strife within the alliance, particularly under the Trump Administration in the United States.

It remains to be seen whether President Trump (or a future Biden administration) will sustain this criticism of other NATO states’ defense spending trends amid this unprecedented crisis.

One thing to monitor is whether these events will further the efforts of some in NATO to define “defense” more broadly, to include costs beyond military forces and operations. Governments in Germany and elsewhere have sought to portray other costs, such as intelligence, public safety and international assistance as being relevant to security expenditures.

The increasing cognizance of public health – surveillance, preparedness, and response – promises to complicate this debate further. Defense budgets, strictly defined, will almost certainly jockey increasingly with other activities under the broad heading of “national security.”

Avascent’s initial estimates suggest that Procurement and R&D allocations will take the largest hits, with many acquisition programs threatened by early termination, suspension, delay or procurement in quantities that lead to higher unit prices.

While our analysis remains ongoing, Avascent projects that European modernization expenditures could face cuts of between $4.9 to $12.1 billion this year depending on the final COVID-19 crisis outcome.

The estimates are based on expected reductions in GDP, which translate into lower defense budgets and the quicker appreciation of USD against the euro and other currencies.

Impact on the Defense Industrial Ecosystem

The impact of all this on the defense industrial base could vary widely, depending on the severity of reductions and how they are apportioned among various priorities. In addition, the resilience of individual companies will be also part of the equation.

Those with heavy commercial aviation exposure will come under much greater strain than those mainly serving defense or other sectors that may fare better in the near-term.

While larger firms may be able to weather the storm on the strength of big balance sheets, powerful lobbying, and durable backlog, smaller providers could be hard-pressed to outlast the downturn.

This could drive how the EU and various national governments structure economic support measures that impact defense investment.

The impending downturn has the potential to accelerate a reshaping of the defense technology ecosystem. Governments will be pulled in multiple directions as traditional firms seek protection and advantage, but new defense suppliers offer the promise of innovation, efficiency, and long-term commercial advantage that could redound to the benefit of the underlying economy.

While this is not a novel tension, the need to preserve employment will be enormously appealing to political decisionmakers seeking to blunt the effects of a downturn induced by COVID-19.

The field of alternative defense suppliers could become even more varied, to include companies with exposure to healthcare supplies, services and information. The potential impact of COVID-19 on the defense supply base will be a subject of further exploration in subsequent papers in this series.

Path Forward

In the light of this multidimensional and still developing crisis, Avascent will continue to refine its estimates for shifts in defense spending and their impact on the global industrial base in the coming weeks.

A series of papers will assess military spending based among individual countries and the sustainability of key modernization programs. We will also look at:

- Spending on operations and combat readiness,

- Potential new opportunities for military suppliers, and

- Measuring the impact on the defense industry ecosystem of economic damage caused by containing the virus.

Avascent’s aim is to help our clients in government and industry consider how a global security crisis from this most unexpected vector will reshape the defense industrial base.