Breaking Bad or Good: Dawn of a New Era for the Defense Sector?

Consolidation among government services businesses has set in motion deal-making that positions the entire federal contracting industry for what could be a fundamental restructuring.

Introduction

Less than a week after Engility closed its $1.3 billion purchase of TASC in late February, news of another major deal broke. SAIC announced it would buy intelligence services contractor Scitor in a $790 million acquisition that will strengthen a highly capable player in one of the US government’s most demanding markets.

Beyond the intelligence sector, these recent transactions are the latest sign of increasing pressure throughout the independent federal services industry for firms to scale up or get out of the market. Facing other newly formed rivals that have rising technical expertise along with low costs, many leading services players now have the mantra “go big or go home.”

For those players at the largest end of the services revenue spectrum, the services divisions of Tier 1 and Tier 2 defense firms, the pressure for growth creates a more challenging strategic decision on the ‘go large’ debate. For the sub $5B Tier 2 service arms, the chosen strategic path has been clearly divest (L-3 Communications – Engility, Exelis – Vectrus). However, for the $5B plus Tier 1 business units (General Dynamics IS&T, Northrop Grumman IS, etc) who are finding scaled growth harder to achieve, and potentially negative to bottom-line company-wide performance—yet complexly beholden to their overhead absorption, the choice is much more difficult.

For competitors of all sizes, the reality of a flat market outlook has created a clear new reality for the federal services sector: eat or be eaten.

Corporate Dynamics: Tough Choices as the Strong get Stronger

Although many await a clear market signal like Defense Secretary William Perry’s infamous “Last Supper” of the 1990s, the government has already made several choices reshaping the federal services segment—and perhaps the broader defense industrial base.

A combination of forces has spurred corporate leadership and boards of directors to pursue significant portfolio changes. These include: Organizational Conflict of Interest (OCI) policy shifts at the Defense Department; budget cuts and caps under the Budget Control Act; preference for fewer but larger contracting vehicles; and a shift to Lowest Price Technically Acceptable (LPTA) contracting.

Broader changes in the industry’s evolving composition actually began as early as 2009 when the Department of Defense began to more carefully monitor Organizational Conflicts of Interest (OCI) issues.

Of course, the biggest drivers of change in the industry has been the decrease in federal spending. With spending peaking around the “surge” in Afghanistan in 2010 and then compounded by fiscal austerity and the Budget Control Act spending caps, the market has since seen a rapid decline in contractor-addressable spending across both the federal services and products markets. Over these past few years, industry has largely coped with a smaller addressable market through aggressive cost cutting of overhead and indirect expenses while pursuing adjacent markets and campaigns to steal market share from competitors.

In addition to reduced budget spending, however, the broader changes in the industry’s evolving composition actually began as early as 2009 when the Department of Defense began to more carefully monitor Organizational Conflicts of Interest (OCI) issues. The result were the parting of ways of some business units from the large diversified contractors, namely in the spin-off of TASC from Northrop Grumman and The SI Organization (now Vencore) from Lockheed Martin. As the government’s fervor for monitoring OCI issues has waned, these moves represent a relatively small shift in the industry’s overall portfolio. However, the creation of a new set of standalone corporate entities free of their former parent’s overhead structure, and focused on the federal services market, is a trend that the market should expect will continue.

Moving into the Sequestration-era of 2011 to 2013, the market saw the creation of additional standalone services firms with the spin out of Engility from L-3 Communications as well as the IPO of Booz Allen and the creation of a number of private equity-backed services platform entities, including PAE. Furthermore, as the Lowest-Price Technically Acceptable (LPTA) contracting wave occurred across most of the federal services market, it became increasingly clear that these new lower overhead companies could compete more effectively in a market that favors lower cost. LPTA has been incredibly disruptive because it largely neutralized the technical and scale advantage that the largest government contractors had spent years developing in the services market.

LPTA has been incredibly disruptive because it largely neutralized the technical and scale advantage that the largest government contractors had spent years developing in the services market.

Due to Sequestration and this paradigm shift to LPTA, competitions emerged as the go-to choice for procurement officials searching for an option that worked with the shifting policy and political landscape. As an example of the growth, the Defense Department used LPTA contracting for 36% of overall contract awards over $1 million in fiscal year 2013, according to the Government Accountability Office, up from 26% in fiscal 2009.

One result from this shift to LPTA was that services-focused operating units within the large prime contractors have since struggled to maintain competitiveness in key services markets. Their higher overhead structure reduced the competitiveness of their pursuits and reinforced corporate leadership’s existing strategy to focus more on returning the cash they had accumulated to shareholders rather than continuing to “invest” in their services lines of business in the face of difficult market conditions. Moreover, the languishing margins in an LPTA environment have made growth a dangerous strategic imperative as it can be non-accretive yet important to overhead absorption.

So why are independent services firms continuing to invest large amounts of capital? The answer is both simple and complex. The simplest explanation is that services companies are rationally focusing on their core market. The more complex discussion however, centers on the importance of achieving scale, capturing positions with adjacent customers, securing positions on key contract vehicles, as well as the influence of private equity-backed investment.

For example, despite the uncertainty caused by Sequestration, CACI acquired Six3 in 2013 (the largest acquisition in the company’s history at over $800M) to add scale and to gain access to new customers across the Intelligence Community (IC) and the defense services market space. Likewise, in late 2012 the newly public Booz Allen Hamilton acquired the Defense Systems Engineering & Support (DSES) division of ARINC, broadening the company’s access to new services market arenas as well as providing access to a pool of lower labor rates. As mentioned above, private equity (PE) firms also continue to show interest in consolidating federal services firms into larger, more scalable players. PAE, backed by Lindsay Goldberg, has grown significantly through the acquisition of CSC’s Applied Technology Division and USIS. Additional deals of note among services firms include, the aforementioned Engility acquisition of TASC and the pending acquisition of Scitor by SAIC.

The rise of these larger, leaner, and more focused independent services firms is creating intense pressure on the services entities within the large diversified primes.

As this trend of additional services company consolidation should be expected to continue in the near future, it should not be considered in isolation. The rise of these larger, leaner, and more focused independent services firms is creating intense pressure on the services entities within the large diversified primes. These business areas, which have traditionally been lower margin than the rest of the prime’s portfolios, are no longer the top-line revenue growth engines that they were throughout the 2000s.

As these pressures mount and the dividend increase and share buyback capital strategies of the primes wind down, they will be forced to deal with this part of their portfolio in ways that go beyond internal cost cutting rounds.

This new phase could result in an acceleration of change across both the services industry as well as the broader defense industry market. Simply put, the sale or spin-out of significant portions of these underperforming business areas from the prime contractors is increasingly likely. Past deals such as L-3’s spin-out of Engility and the Exelis spin-out of Vectrus offer a template, albeit still on a smaller scale than what could ultimately happen. The result is twofold: diversified primes will likely carry a much smaller and focused services line of business in the future, and the creation of even more large and lean services-focused businesses due to divestiture activity by the primes would further reshape the market’s competitive dynamics.

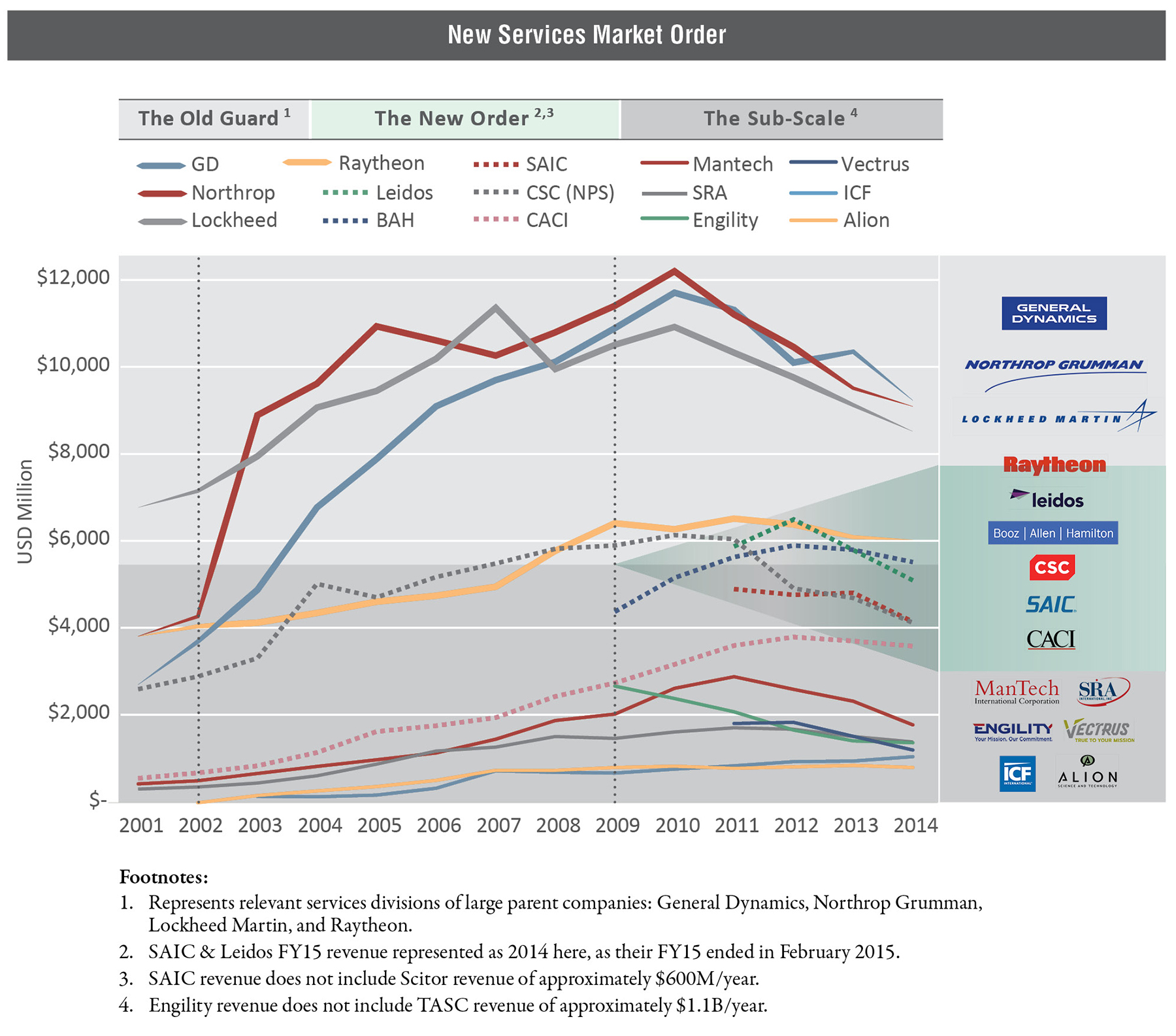

Another way to look at this emerging development is to examine revenue trends across a sample of leading services organizations over the past decade.

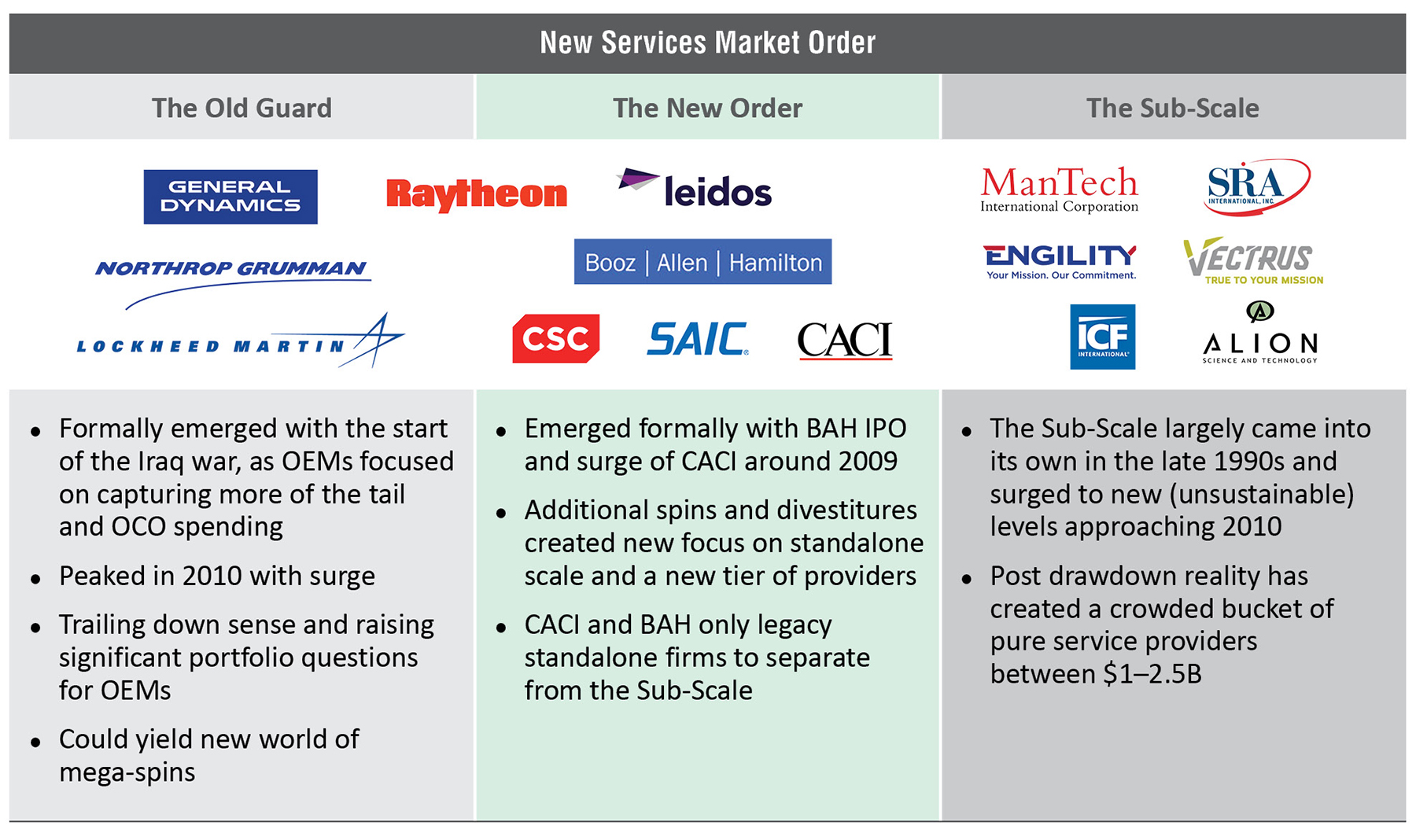

This information reveals an emergent taxonomy of players that will shape the future of the services market: 1) “The Old Guard,” consisting of the appropriate services divisions within the leading prime contractors; 2) “The New Order,” or large services firms that have driven growth over time through continued investment (largely through acquisitions) in their core services markets as well as the first wave of diversified players; and 3) “The Sub-Scale,” consisting of large services firms whose growth has stalled and hasn’t yet begun to reach the scale of either the larger standalone firms or the services business areas within the primes.

As the Old Guard can no longer look to their services business to generate revenue growth, it is logical that corporate leadership will focus elsewhere. As the market has experienced, this involves returning cash to shareholders and investing in core businesses rather than seeking to bolster their services divisions. For all categories of companies, focusing on core market areas during tough market conditions is often the appropriate strategic move which helps create a stark contrast between the Old Guard and the New Order class of companies.

While the Old Guard focus on returning cash to shareholders, the New Order class of companies is grabbing market share through aggressive pricing on core services work and the acquisition of companies that provide scale, new customers, and valuable positions on key contract vehicles. Lastly, one can also identify a set of significant services players that have been unable or unwilling to seek greater scale through inorganic investment, whose revenue streams have gone largely sideways to slightly negative since the peak of the market. Like the Old Guard firm, which is unable to invest in its services business, the Sub-Scale will either have to cut fees in order to maintain revenue or seek strategic alternatives to those New Order firms that are economically positioned for future acquisitions.

These changes have the potential to ripple throughout the entire industry if they occur. In the services market, newly divested standalone services entities would bring a lower overhead/leaner cost approach along with scale and engineering expertise that exceeds most of the existing independent services players. Likewise, on the other side of the prime contractors’ portfolio, once free of underperforming units and armed with the proceeds from a sale or a spinoff, they could become aggressive acquirers within their own core products and solutions markets. It may even facilitate consolidation among the “Top Ten” government contractors that, to date, has been seen as unlikely.

With a balance-sheet boost from a service division sale or spin-off, boards of directors will have new options. This could lead to a swap-out phase, where even commercial or international holdings replace services in a corporate portfolio. Certainly, mid-tier firms such as Cubic, Rockwell Collins, ViaSat and FLIR would become even more attractive acquisition targets of the largest primes. Within the industrials sector, a similar portfolio refining could take place with their defense units, as United Technologies’ exploration of a sale of Sikorsky shows. Similarly, Textron’s defense business could be a factor or UTC might make additional divestitures of Pratt & Whitney and Goodrich. There are many compelling strategic options for those larger primes looking to exit the services market and focus on core aerospace and defense businesses.

There are many compelling strategic options for those larger primes looking to exit the services market and focus on core aerospace and defense businesses

Conclusion

Spurred by changes across the services sector, the federal contracting industry may be reaching a point where reorganization is likely to continue, if not accelerate. As these changes unfold, current management, investors and boards of directors should consider the following:

Small/Mid-Scale Services Firms

Focus on core customers and defend/invest in areas of technical expertise. This approach will help maintain market share, fight the increasing scale and low-cost offerings of an emerging class of large services companies, and create attractive exit alternatives to new tier of players. If the corporate portfolio lacks differentiated revenue, consider strategic alternatives.

Small Businesses Overall

Avoid low-cost/undifferentiated areas of the market in exchange for developing strength in customer relationships and critical skill sets. This approach will either increase valuation to would-be acquirers or allow a company to develop long-term strategies to weather this current round of reorganization.

Mid-tier Defense Players

Select companies have commercial- and defense-market exposure. This should be used to their advantage by leveraging defense-oriented capabilities into the commercial markets. This requires thinking about, and investing in more than core government customer requirements. Instead, focus on next-generation technology, advanced manufacturing methods, and other key differentiators that will allow you to provide value to government customers and defense primes.

Large/Stand-Alone Services Firms

Despite current first-mover advantage, prepare for the creation of additional lower overhead peer competitors through the spin-out or private equity placement of a major line of business from the diversified prime. Position on large contract vehicles will become even more critical, but so will the development of key technical offerings that can compete against these new potential competitors.

Diversified Prime Contractors

Build robust shareholder value models comparing current structures to one that returns value to shareholders, possibly through a tax-free spin-off of a significant portion of a company’s current services business. Should a spin-off of a new services entity make sense, ask – and answer – the question of what additional value can be created with a leaner corporate structure and additional cash on the balance sheet.

The restructuring of the services market will continue, and likely become even more dynamic as company leaders and boards of directors have new strategic options. The question for the broader government contracting industry is then: what impact will these changes have on corporate strategy? Currently, there is the potential to trigger major shifts in the industry’s structure through divestitures and spin-offs, an accelerated M&A deal flow and a growing need to satisfying growth-seeking investors. When the SAIC and Scitor deal closes this May, do not be surprised to see more new deals taking the spotlight through the rest of 2015 and into 2016.