Rebalancing Your Organization: Small Adjustments Can Make Big Differences

Leaders of all organizations – companies, government agencies and non-profits – must constantly decide when and how to adapt their organizations to shifting environments. External market changes, such as evolving customer demands, disruptive competitive threats, and new regulation are regularly buffeting established organizational models. Similarly, internal developments, such as aging workforces or ever-changing employee expectations, can render previous organizational structures, processes, and norms progressively less effective.

And, with new forms of communication and information sharing, these shifts are often happening faster and more frequently than in the past – forcing leaders to be ever more agile.

Keeping on top of this dynamic environment is hard enough. Knowing when and how to take action is even harder. The natural response for some leaders is to put off difficult actions that affect how their organization operates, soldiering on even when they know that they are performing less effectively than they could. In many cases, this reticence to change arises because “organizational change” has too often become synonymous with large, disruptive, and often painful reorganizations that many times yield only modest results. Given this, it is not surprising that leaders are often reluctant to quickly address organizational challenges, and can lack conviction when they do.

Organizational change” has too often become synonymous with large, disruptive, and often painful reorganizations.

While there is no silver bullet for keeping organizations agile and effective, there must be a better way to adjust and adapt rather than waiting until only a major overhaul will suffice. Our work across dozens of diverse organizations (from Fortune 100 companies to small businesses, government agencies and non-profits) suggests that adaptive change need not be disruptive and painful. Leaders can keep their organizations balanced and effective by understanding specific enabling components and how they are responding to market and environmental shifts – and then taking relatively targeted, incremental actions to rebalance.

Three simple guiding principles can help:

- Be self-aware and specific: Recognize how and to what degree individual enabling components of your organization are adapting, or not adapting, to shifts in the internal and external environments.

- Maintain a running conversation: Regularly engage a range of stakeholders to understand changes affecting your organization, and get their perspective on implications for the organization as a whole, as well as the specific enabling components.

- Rebalance before you reorganize: Identify those key components of your organization where small adjustments will bring the greatest value. Then start with relatively small, high-impact modifications long before you feel forced to embark on more painful, comprehensive reorganizations.

Building a Balanced Organization

Regardless of the type of organization they lead, executives face a common root cause of underperformance: organizational imbalance. Organizations that possess the right mix of people, processes, tools, structure and communication forums achieve balance and can deliver exceptional performance. However, when these enablers of performance are unevenly developed, the overall organization becomes out of balance. Imbalance can manifest itself as “process creep” that bogs down decision-making; as eroding communication between employees in a growing organization; or as shortages of key skills needed to meet new customer needs.

Our experience suggests many of the best leaders frequently take a systematic and comprehensive look at their organizations to understand how change is affecting, or will affect, them. They look at the specific dimensions of their organization and ask questions such as:

- Have we adjusted our strategy and mission to address the internal and external challenges we face?

- Are we structured appropriately?

- Do we have the right people with the right experience, skills and knowledge?

- How effective are our key processes? Are there too many? Or too few?

- Are we communicating – both formally and informally – effectively with each other?

- Do employees have the tools and infrastructure they need?

- Do our organizational metrics and incentive systems align with our strategic objectives?

Regularly taking this structured approach enables leaders to gain a consistent picture of how the organization is performing. While it can highlight problems early, it can also identify unexpected opportunities. For example, leaders at one public sector organization believed that many of their organizational challenges were a result of ineffective processes. After taking a comprehensive look at the situation on the ground, however, they realized the root issue was not process, but ineffective communication among employees and the lack of some basic tools. The fix was smaller, quicker and had far wider benefits than anticipated.

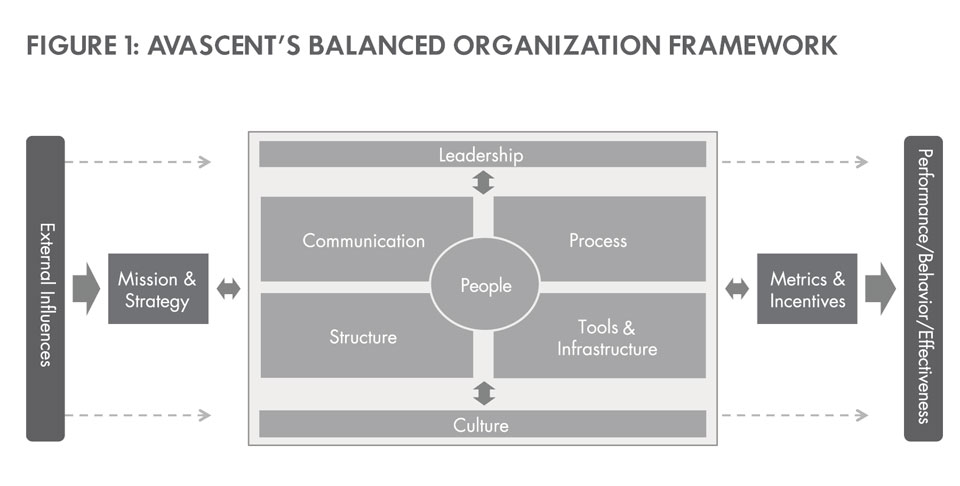

Avascent’s Balanced Organization framework (Figure 1) was derived from decades of experience advising leaders on such structured examinations of their organization’s effectiveness.

Maintaining organizational balance requires a constant effort. Even the best organizations will fall out of balance over time. The key is to catch these imbalances early – before they become larger and more painful to solve. To ensure that their organizations stay balanced, leaders can follow three simple principles:

1. Be self-aware and specific.

The Balanced Organization framework highlights a proven way that leaders can keep track of specific, inter-related “performance enablers” and understand how each is contributing to overall effectiveness. This goes beyond checking on how Finance, Sales, Marketing, and HR are performing. Instead it requires looking at the foundational enablers of performance in an ordered way (see Figure 1): Mission & Strategy, Leadership, Structure, Communication (internal and external), Process, People, Culture, Tools & Infrastructure, and Metrics & Incentives. Assessing these enablers in a well-thought-out way helps define where specific changes will have the greatest impact – and just as importantly, those areas where change is not needed.

The best leaders constantly seek information about internal and external shifts and how they are affecting specific components of their organizations.

Problems are rarely solved only through changes in reporting and management structures or simply the deployment of some new tool. These can provide a short-term fix, but the root causes of issues will almost always re-surface.

By viewing the organization through the lens of the Balanced Organization framework, leaders can see the interrelationships between the critical enablers of performance, identifying problems and opportunities early and focusing attention on where change is most needed.

2. Maintain a running conversation.

Some change is predictable – the founder of a fast-growing start-up has to decide when and how to “formalize” employee roles and customer management. Other developments come as surprises – a competitor introduces a truly disruptive product or steals a strategic customer. And some changes are slow and subtle – erosion of staff morale, obsolescence of a key product – and can go largely unnoticed until the situation becomes critical.

The best leaders constantly seek information about internal and external shifts and how they are affecting specific components of their organizations. But, more importantly, they also discuss these developments frequently – both understanding the implications and building a shared sense of where the challenges for the organization may lie.

Running conversations that are formal, as in a strategic planning process, are valuable. But less formal conversations can be equally important. The give and take during staff meetings, lunch rooms, online forums, or on the road can all help leaders stay current and in tune with how the organization is operating.

These conversations should engage the full range of stakeholders, both inside and outside the company and address the central issues affecting the organization: What are your toughest competitors doing? How are you responding? How do your best customers and stakeholders feel about your performance? How is staff morale and retention? What’s the status of major internal initiatives? The answers to these questions provide a means for ongoing identification of organizational imbalance, as well as potential solutions for rebalance.

3. Rebalance before you reorganize.

A current, comprehensive perspective on how components of an organization are performing and reacting to change enables leaders to pursue more focused efforts aimed at rebalancing the key enablers of performance rather than undertaking titanic overhauls.

While large-scale reorganizations can be necessary in some situations (e.g., in the wake of a bankruptcy, divestiture, or a “bet the company” shift in strategy), they can also be disruptive and less productive than leaders hope at the outset. For example, the US Postal Service implemented a major reorganization in 2008, only to be followed by another one less than three years later when it became obvious that the first did not yield the promised improvement. Given the trauma of such undertakings, the natural tendency for many leaders and their staffs once a major reorganization is done is to put further thought about how to calibrate the organization’s performance on the back burner. This only sets them up for another major reshuffling as the organizational impact of subsequent internal and external changes accumulate.

Avascent’s work suggests that often the most appropriate (and least disruptive) method to keep organizations agile and responsive in the face of change is to undertake targeted adjustments – and to do so relatively frequently.

The Balanced Organization Framework in Action

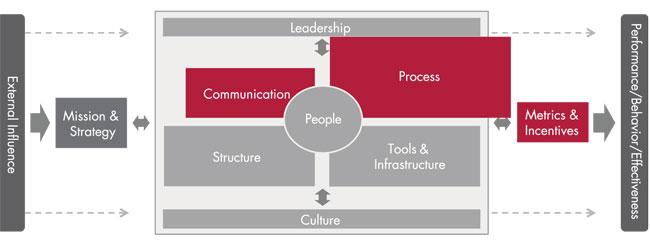

The value of the Balanced Organization framework becomes clearest in its application. For example, a mid-sized government organization was unable to effectively implement its new strategy to engage with a wider range of public and private sector partners. Interviews with staff at various levels suggested that support for a new strategic initiative was uneven due to a sense of inertia and a long history of poor communication among stakeholders. As a result, the organization had overbuilt its processes to serve as a substitute for more effective internal communications, creating a lengthy series of reviews that stymied even the best initiatives. Complicating it all was an incentive system that offered no reward for success (see Figure 2).

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Fortunately, senior leadership was fully engaged, both in articulating the strategy and discussing the challenges the organization was facing in implementation. Most importantly, they were keenly focused on the enablers of organizational performance, seeking to diagnose precisely where the impediments were and how they could be addressed.

To make sure change would succeed, leaders zeroed in on the biggest problem areas: simplifying accumulated processes, improving both formal and informal communications and adapting metrics and incentives to clearly link to organizational objectives. Implementing these changes was still challenging, but far easier, faster and more impactful than taking on a large scale reorganization (or simply doing nothing). These changes allow the agency to successfully execute its new strategy of actively engaging with a wider range of new external partners.

Concluding Summary

Leading any organization is a constant challenge, with the toughest decisions being when and how to make changes in the organization itself. Avascent’s experience suggests frequent and open dialogue about environmental change, taking a structured and comprehensive look at the organization’s strengths and challenges and biasing toward regular, targeted adjustments can help all leaders keep their organizations agile and effective.