Getting in on the Lab Floor: Industry Must Adapt to Pentagon RDT&E Shifts

After nearly two decades consumed by counter-insurgency campaigns, the Pentagon means what it says about elevating high-end conflict to the forefront of budget priorities.

After nearly two decades consumed by counter-insurgency campaigns, the Pentagon means what it says about elevating high-end conflict to the forefront of budget priorities.

As foreshadowed by the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), the 2020 budget request outlines a wide range of new priorities and record-setting Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding.

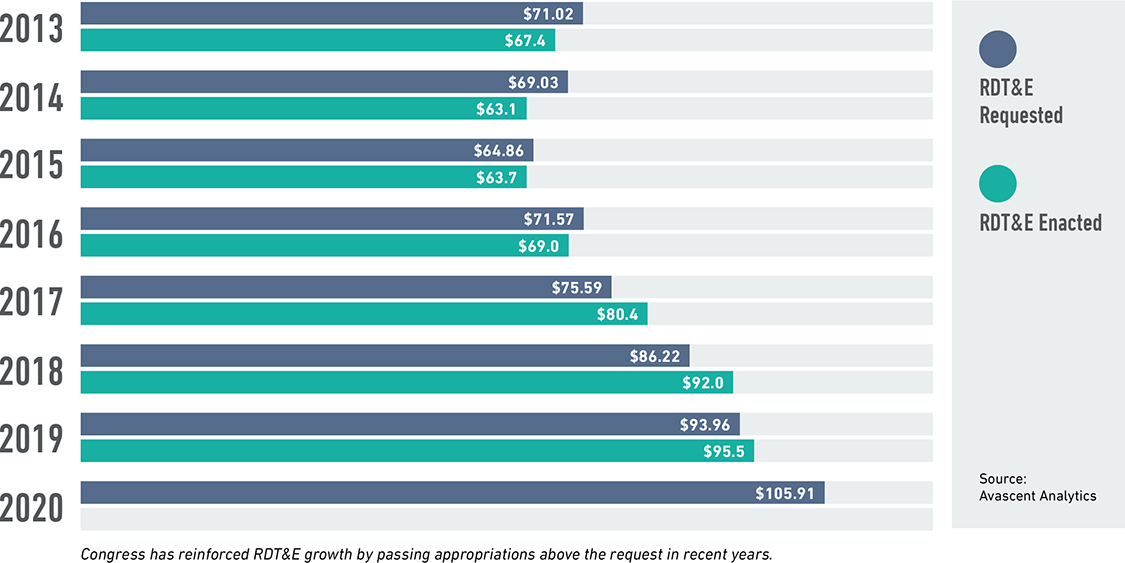

This expansion is part of a broader trend: from FY16 through FY19, RDT&E spending rose substantially by an 11 percent compound annual growth rate and has consistently outpaced the overall Department of Defense (DoD) budget. This funding will peak at over $100 billion in 2020 with the first budget request designed to fully reflect the priorities of the NDS.

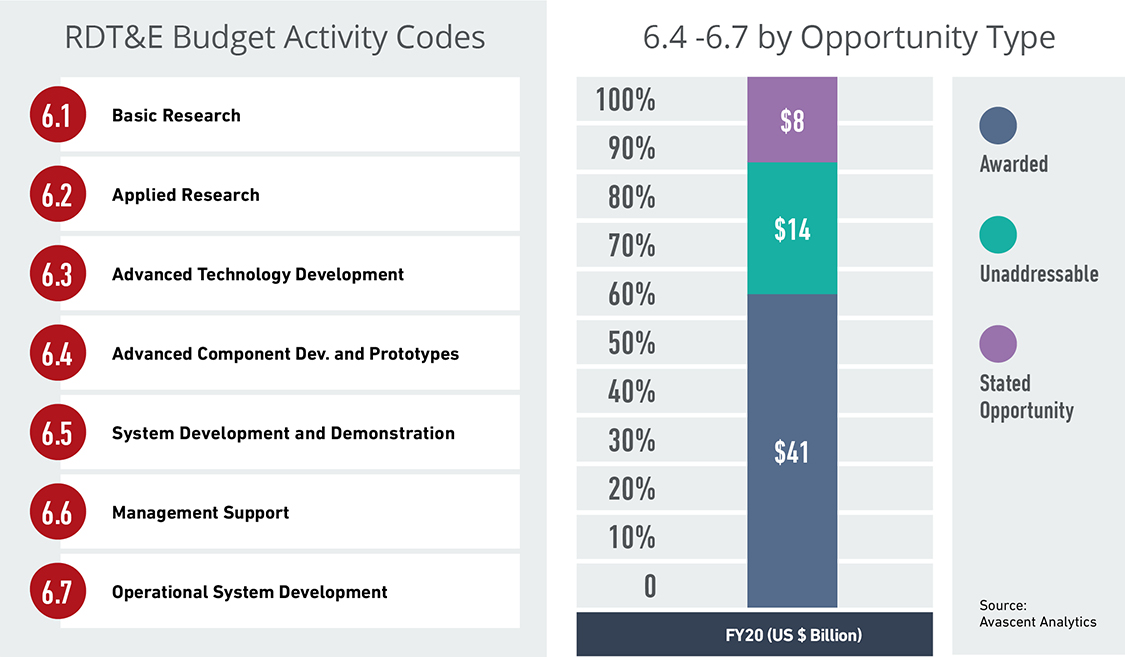

Yet despite the growth, there are expected to be fewer new development programs than in the past. Nearly 90 percent of the later stage research and development funding is already effectively spoken for by a handful of programs. These programs will offer opportunity for some industry players, but they are competitive and limited in number.

Alternatively, future-oriented Science and Technology (S&T) – which is in essence early stage RDT&E – will be increasingly critical to shape outcomes, requirements, and program choices.

Standing at nearly $16 billion overall in FY20, S&T funding is substantial, and there are many points of entry across the Services, as well as DARPA. Yet, in years past it has been difficult to find many clear-cut cases of this S&T translating into acquisition programs.

With DoD’s emphasis on using new development models to bring promising technologies rapidly into the force, industry should now start to see a more direct benefit from S&T contracts.

Today many Pentagon leaders are advocating a different innovation and procurement approach, in which new technologies are more quickly and frequently developed and inserted into platforms and programs – then upgraded regularly thereafter (not necessarily by the original prime contractor).

This shift suggests that promising technologies generated at the S&T phase will be fast-tracked through (or around) the acquisition system to be integrated into existing programs (or become their own).

RDT&E Requested vs. Enacted, 2013-2020 (US $ Billion)

Rising Defense Tide Lifts RDT&E

RDT&E has outperformed overall DoD topline growth since the Budget Control Act-driven downturn in defense spending. The difference in growth reached its peak in 2017, signaling a shift of DoD priorities toward next-generation capabilities that persists today.

DoD Topline vs. RDT&E Growth, 2013-2020

Budget activities 6.4 to 6.7 account for the majority (85 percent) of RDT&E spending, as programs of record mature towards production and procurement. At the top of the list is the B-21 Long-Range Strike Bomber which, at $3 billion, receives three times as much late-stage funding as the next largest program (consistent with the ambitious goal of achieving the first flight of the B-21 by FY21).

Nearly 90 percent of the latter-stage unclassified funding is already under contract or represents work being performed by the government through the military labs or Office of Development Test & Evaluation.

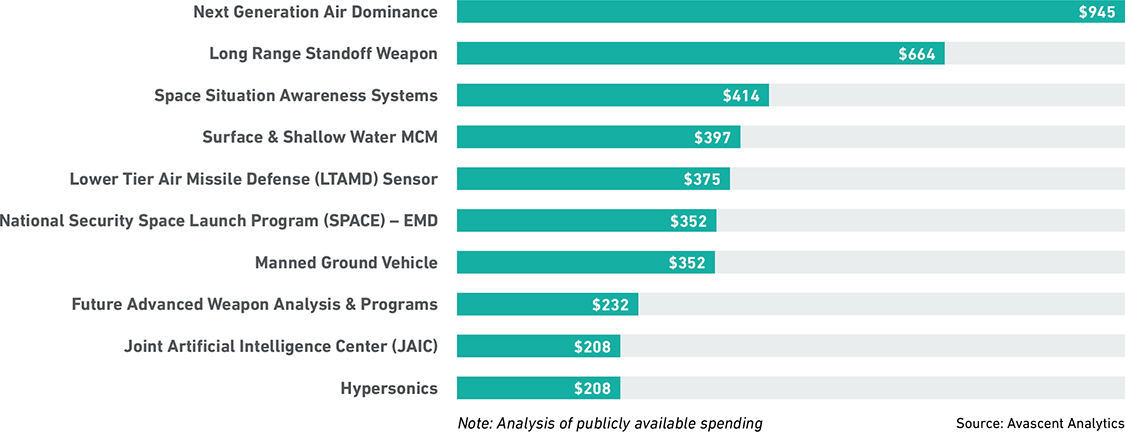

The roughly $8 billion remaining – which, in principle, are available for new bids – are weighted toward major programs, such as Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) and Long Range Stand Off (LRSO).

These kinds of programs have been longer-term priorities for prime contractors that have already invested substantial Independent Research & Development funds or received initial technology maturation contracts from the government.

Some, like NGAD, will grow aggressively over the next decade and provide more opportunities to other firms for sub-systems development.

FY20 Top Opportunities in 6.4-6.7, (US $ Million)

New Opportunities in S&T

The earliest stage RDT&E budget categories (6.1-6.3) that make up the Science & Technology budget can provide a more promising area for those seeking to influence, and ultimately benefit from, the next major programs.

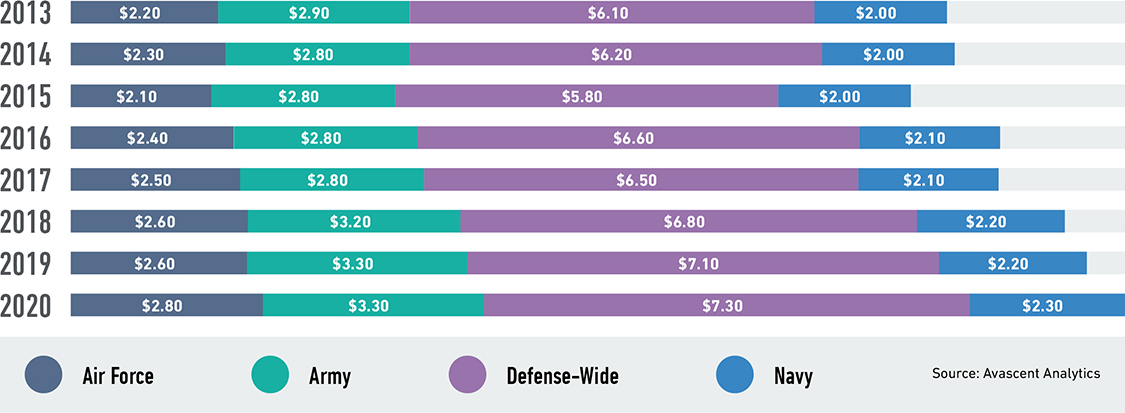

Over the past decade, S&T spending has averaged between two to three percent of the total DoD base budget and 12 to 14 percent of RDT&E requests. Defense strategy documents, non-governmental reports, and Congressional legislation have consistently called for S&T to receive a higher share of defense spending.

In fact, Congress habitually builds significantly on top of DoD’s requests for S&T, which is why year-to-year increases in budget requests can appear as spending decreases when compared with the prior year’s enacted level.

The largest sources of S&T funding are defense-wide (DW) agencies led by OSD & DARPA, followed by the Air Force, Navy, then Army.

S&T Spending by Customers, 2013-2020 (US $ Billion)

In FY17 and FY18, industry received more than 40 percent of that funding, more than any other recipient. The next largest recipients were other government entities (called “intramural”), followed by universities and FFRDCs.[1] Across the DoD, DARPA spent the highest percentage of S&T funds on industry, while the Navy spent the lowest.

Inside the S&T Black Box

Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (R&E) Dr. Michael D. Griffin has listed five priority areas for his division and RDT&E spending generally: autonomy, cyber, directed energy, hypersonics, and next generation space.[2]

Key S&T Categories in the FY20 Request, (US $ Billion)

The stated top priorities will lead headlines and make up a significant portion of the FY20 S&T request. A closer look at S&T spending, however, suggests that funding exists in many other places.

It is critical to investigate labs closely to uncover not only their current work but also their future unmet needs. There is ample leeway for industry to shape future programs and align its own RDT&E portfolios with military priorities and gaps.

Avascent analysis of FY19-20 S&T coded programs provides examples of where DoD and the Services are probing for breakthroughs that could potentially transform warfare.

Biotechnology

- There are more than 30 bio-tech labeled programs across the services and DARPA

- DARPA will focus its Bio-Security program on developing new ways to detect emerging pathogens and other biological threats ($15M)

- The Navy will study “bio-inspired autonomous systems” ($20M)

Human Enhancement

- The Navy will explore human decision making to improve human-machine teaming ($19M); the Air Force is pursuing a

- similar but separate effort ($20M)

- The Air Force Human Effectiveness Program will explore augmentation techniques for physical and cognitive performance optimization ($14M)

Super-Computing

- The Army will continue maturing its High Performance Computing Modernization program, which builds supercomputers

- that performed 31 trillion floating point operations per second last year and will target 51 trillion this year ($97M)

- The Army’s CREATE project ($54M) will continue to pursue supercomputer-based modeling in support of rapid prototyping and acquisition

- The Air Force’s game Changing Computing Power ($5M) will seek to enhance computing power for autonomous systems and other applications

- DARPA’s CHESS program ($20M) will develop software that will help computers and humans analyze code to identify and mitigate vulnerabilities

- DARPA’s Beyond Scaling initiative will allocate $40M to produce software to automate and optimize chip and board design

Electronic Warfare

- The Air Force will invest over $50M in its RF Sensors and Countermeasures Technologies research project through

- four funded lines of effort that span sensor development, beam forming technology, and model and simulation

- The Navy’s Electromagnetic Systems Advanced Technologies project will see $10M in funding in 2020, over half of which will be dedicated to developing jam-resistant positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) systems

- The Air Force’s EW Quick Reaction Capabilities program will rapidly prototype technologies across electo-optical, radio

- frequency, and space-based aspects of electronics warfare ($30M)

S&T’s Evolving Role

Industry has always had a stake in defense S&T given its role as the “seed corn” of future military modernization programs – though it was seen often as a double-edged sword. On the positive side, the S&T contracts funded firms’ labs and technology divisions, and fostered relations with DARPA and the military labs.

However, if industry produced a technological breakthrough via an S&T contract, it has no assurance that it would be able to capitalize on it later if that innovation became part of (or was the basis of) a new program. The government owned the intellectual property and would award the subsequent development and production contracts according to its requirements and preferences.

Clear cases of a firm’s S&T work leading to substantial revenue-generating programs were elusive. As such, industry often considered S&T projects with the military labs largely as an afterthought – or, at minimum, a productive and prestigious activity for corporate technology divisions – but not a business development priority.

In line with the NDS guidance, many Pentagon leaders are now advocating a different innovation and procurement model. For example, the Army’s Future Vertical Lift (FVL) will separate procurement of the helicopter airframe from the mission systems inside, requiring the platform to have “plug and play” built into the design from the outset.

The emphasis will be on rapid funding and prototyping of multiple smaller programs under a “fail fast” model, a process US Air Force Assistant Secretary for Acquisitions Will Roper said was “like running naked through briar patch.” This mindset is increasingly becoming the norm for defense leaders and acquisitions experts across the political spectrum, suggesting that it is here to stay.

The commercial sector intends to be a promising source of rapid innovation, but there will naturally be limits to what those “non-traditional” companies can or will do. Faced with the uncertainties and limitations of widely adopting commercial technology, the Pentagon will still need to ensure that its own S&T pipeline plays a central role in building the future force.

utilize defense S&T successes to shape new

acquisition programs or disrupt existing ones."

Implications & Challenges for Industry

Given this new reality, industry must increasingly utilize defense S&T successes to shape new acquisition programs or disrupt existing ones. Just as DoD is adopting more of a portfolio approach to RDT&E, so too should industry assess product investments collectively from an enterprise level, rather than as independent and unrelated initiatives.

This means industry will need to:

- Align for the technologies of tomorrow, not the programs of yesterday:

- Coordinate among internal business development, technology, and strategy organizations. Establish an enterprise-wide strategy for S&T, as well as RDT&E more broadly.

- Unlock the black box: Develop a comprehensive understanding of how lab priorities align with the existing portfolio and pursuits. This should inform lab engagement and internal investments.

- Know the customer: Send “boots on the ground” to the labs and prioritize relationships with customers. Or consider strategic partnerships with companies that have strong lab relationships.

To be sure, the perennial challenges in defense acquisitions remain. Despite the many initiatives underway – including use of Other Transaction Authorities (OTA) – to bring new technology directly into the force faster, the proverbial “valley of death” is still wide and deep.

Nonetheless, in this new acquisition environment industry cannot afford to maintain an arms-length and episodic approach to S&T projects and the labs. As the timeline from drawing board to lab to battlefield shortens, defense firms risk being left behind. Those companies that adapt to these new realities will be best positioned to reap the benefits.

[1] https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/fedfunds/2017/html/ffs17-dt-tab010.html

[2] Estimates based on text analysis of approximately 2,500 S&T cost element descriptions in the FY2020 request