New Customers for Chinese Weapons: Opportunities for Chinese Arms Exports in the Western Defense Marketplace

As the People’s Republic of China celebrated 70 years of Communist rule on October 1, 2019, many were fixated on the military parade showcasing the advanced military equipment of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Versions of these advanced systems will likely soon be sold worldwide, as Chinese arms exports have expanded alongside China’s global political and economic interests.

The increasing sophistication of Chinese weapons presents potential competition to Western arms makers, especially as some customers who have traditionally bought Western arms face budgetary and political pressures.

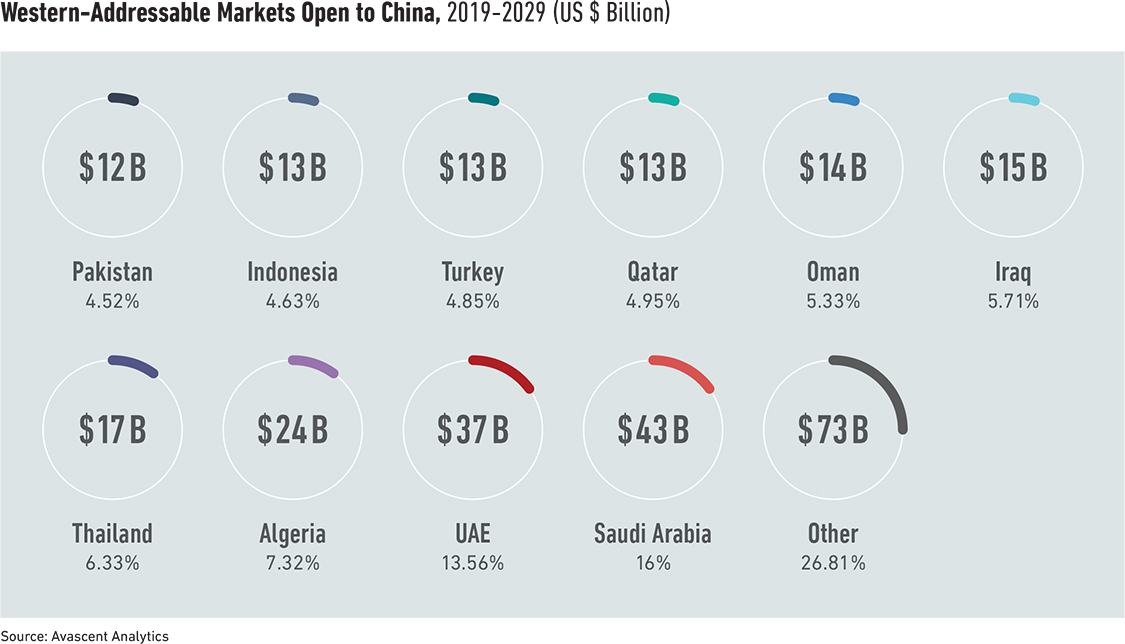

Avascent estimates that over the next 10 years Chinese firms could compete for $275 billion of the Western-addressable defense marketplace.

Expanding Chinese Arms Exports Among Traditionally Western Customers

Prior to 2010, the annual value of Chinese arms exports struggled to reach even $700 million. Since then, annual exports have been consistently above $1 billion, sometimes breaching $2 billion.[1]

Where Chinese firms before could only offer inexpensive or low-end equipment, these same firms are now offering sophisticated, high-value systems.

Yet, customer national security and politics will influence Chinese market addressability more than technology. The ability to expand Chinese arms exports among traditionally Western customers will rely on four major market factors:

- Budget limitations,

- Support of local defense industrial interests,

- Supplier diversification, and

- Immediate security needs

Budget Limitations

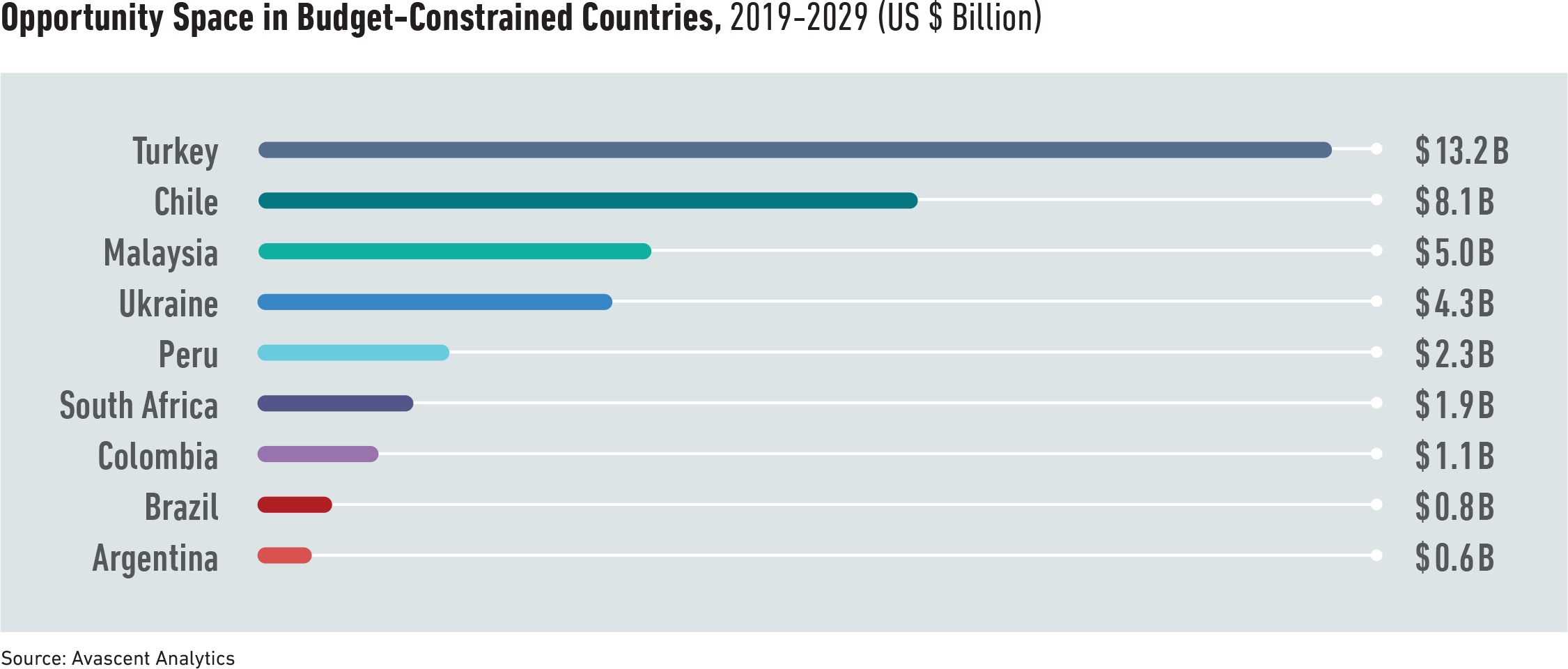

Catering to customers with limited budgets has been the forte of Chinese arms exports for decades. Customers that fall into this category include

- Argentina,

- Brazil,

- Chile,

- Colombia,

- Malaysia,

- Peru,

- South Africa,

- Turkey, and

- Ukraine.

Opportunities that China can address in these countries alone add up to more than $37 billion over the next decade.

South American countries Chile, Peru, Brazil, Colombia and Argentina feature heavily here due to the relatively low regional threat environment, which primarily consists of enforcing internal security and addressing transnational threats such as smuggling and drug trafficking.

Fiscal pressures and unfavorable exchange rates, issues which are particularly significant in Brazil and Argentina, further dampen defense budget growth and purchasing power.

defense budget constriction and a potential opportunity

for Chinese defense firms."

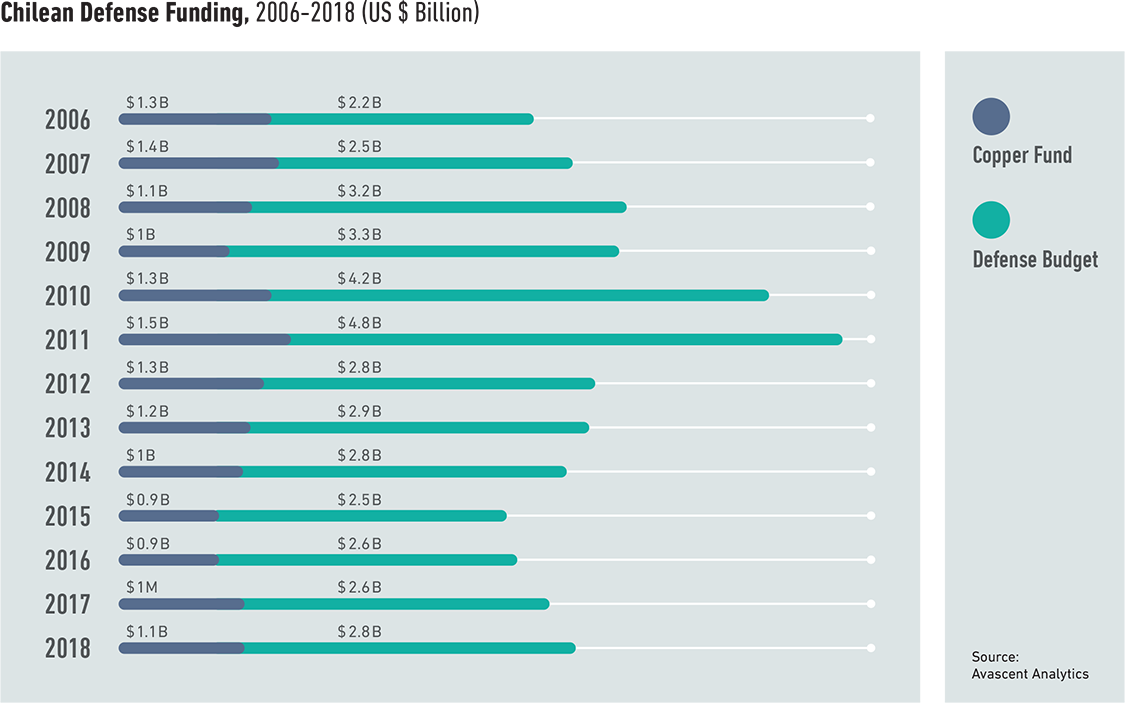

Chile in particular presents a good example of future defense budget constriction and a potential opportunity for Chinese defense firms.

Chile’s defense spending has been supported by the Restricted Law on Copper, which has routed more than $12 billion in natural resource revenues to defense spending over the past decade, accounting for more than 27% of Chilean defense spending during the same period.

But this policy was reversed earlier in 2019, which will eventually eliminate this source of funding by 2029. This, combined with a low threat environment, may lead the Chilean Ministry of Defense to prioritize cost effectiveness with its limited funds, moving away from high-end Western platforms.

Chinese offerings could be competitive in major future acquisitions such as new armored vehicles to address internal security and UN peacekeeping missions, and new fighters to replace Chile’s F-16s.

Argentina, Brazil, and Turkey are also potential markets of interest for Chinese arms exports in part because of their weakening currencies, which degrades dollar purchasing power.

As an example, at the start of 2018, the Argentinian peso was valued at about 20 pesos to the US dollar. Since capital controls were imposed this September, the peso has plummeted to 56 to the dollar.

US wariness of Chinese arms sales in the Western Hemisphere may deter some Latin American customers from large Chinese purchases.

However, unless more affordable and cost-effective solutions can be put forward by other providers, Chinese equipment is likely to proliferate, become increasingly attractive out of financial necessity.

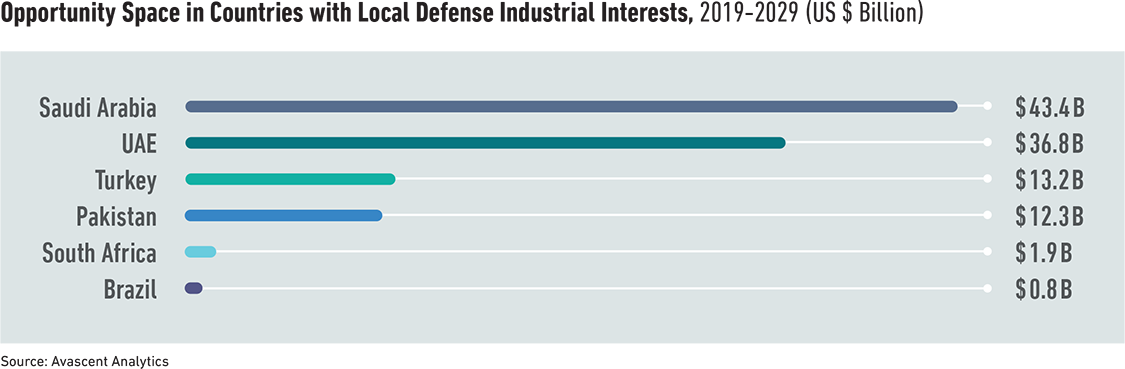

Local Defense Industrial Interests

For many countries, support for the local economy drives decision making, as local defense industrial bases are national assets that provide jobs as well as the potential for future exports.

Governments under pressure to keep their defense industrial bases alive, or those with ambitions to become significant defense exporters, include

- Brazil,

- Pakistan,

- Saudi Arabia,

- South Africa,

- Turkey, and

- the UAE.

In South Africa, national defense industrial champion Denel has been in dire financial straits for the past few years, and last August received a 1.8 billion rand ($120.4 million) government bailout.[2]

South African defense spending is unlikely to grow significantly, compelling Denel to find international customers in addition to securing the home market.

South Africa’s modest defense procurement spending is not sufficient to support Denel, and much of that spending goes toward higher-end systems that Denel lacks the resources and expertise to address.

Partnering with Chinese firms on development projects may present an intriguing, if not ideal, option for Denel. The company acknowledged its need for outside help when it signed a memorandum of understanding with Poly Technologies for naval shipbuilding three years ago, attracting scrutiny shortly thereafter.

Such cooperation may help the company develop higher-end offerings with lower research and development costs, while injecting advanced Chinese expertise and technology into the company.

For the South African government, this could make for procurements that are easier on its limited budget, while still supporting local industry.

Turkish defense firms, on the other hand, do not appear to have financial troubles of such scale. Rather, they have been building an impressive portfolio of weapons, and the government aspires to expand weapons exports significantly.

Yet recent tensions between Turkey and the rest of NATO, highlighted by its expulsion from the F-35 program, bring into question whether Turkish firms can continue to access key subsystems from the West.

Given a weakening Turkish lira and immediate security needs along the Syrian and Iraqi borders, Turkey may see a need to diversify its supply chain not only to equip its own forces but also to continue importing foreign expertise and components to support the local defense industry.

China already has some history with the Turkish defense industry, as Roketsan’s T-300, Bora, and Yıldırım missiles are based on Chinese systems.

Defense Supplier Diversification

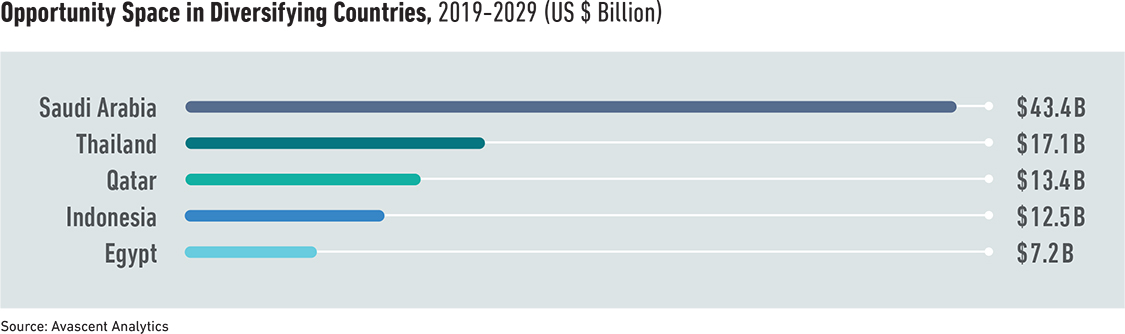

Countries that have relied heavily on Western equipment in the past, including Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and Indonesia, are increasingly diversifying their defense suppliers.

Qatar’s notable acquisition of F-15’s, Eurofighter Typhoons, and Rafales, which increased the size of its fighter fleet from around 12 to 92, is a prime example.

Leaders in other Gulf and Mideast states are wary of Western willingness for rapprochement with Iran, and German export restrictions portend increased difficulty for future imports of weapons from the West. Conversely, customer changes affect sales as well.

Canada barred export of helicopters to the Philippines, due to serious human rights violations linked to Philippine President Duterte and his anti-narcotics campaign.

Regardless of the concerns and merit of such policies, these developments highlight the geopolitical vulnerabilities of dependence on a narrow set of suppliers. Diversification ensures a constant supply of equipment.

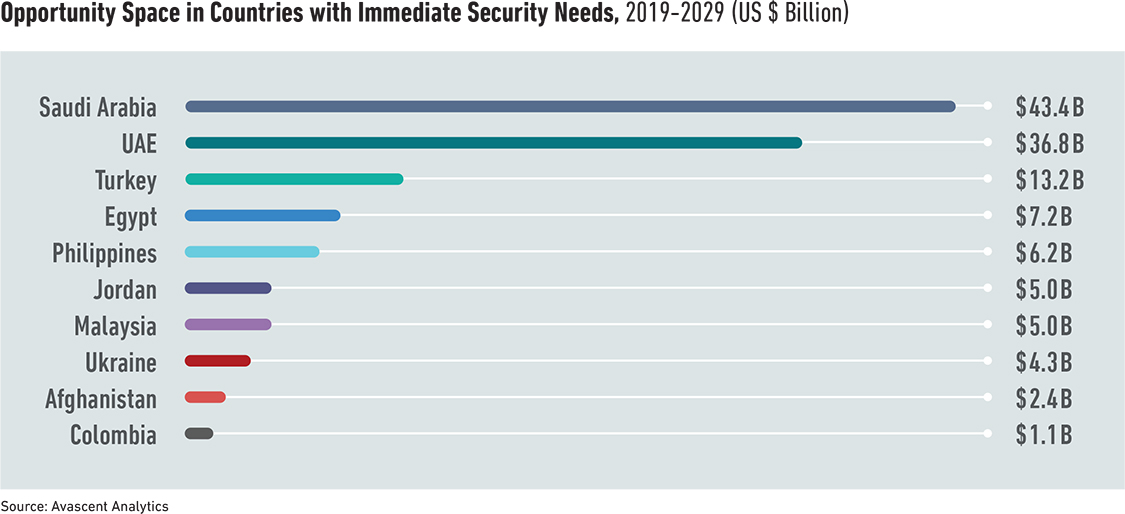

Immediate Security Needs

The worst-case scenario for any military would be a failure to resupply during hostilities. Indeed difficulties in procuring drones from the US created an opening for Chinese CH-4 drones to enter the Middle Eastern defense market and support operations against ISIL and Houthi rebels.

Though exact figures are not openly available, Avascent estimates almost $1.2 billion has been spent by Middle Eastern and North African countries on Chinese drones and associated weapons.

This includes a significant Saudi purchase estimated at $700 million, encompassing extra costs for technology transfer and local production.

Such openings in the market can have long-standing effects, as demonstrated in Indonesia. Western countries largely supplied the Indonesian military (TNI) under President Suharto. In 1999, the US imposed an arms embargo on Indonesia after human rights abuses in the 1999 East Timor Crisis.

The timing could not have been worse, as an insurgency in Aceh province intensified following Suharto’s fall the previous year. A few years after the embargo was imposed, the TNI ordered its first fighter aircraft from Russia’s Sukhoi in 2003.

Even though the embargo was lifted in 2005, the TNI continued to order Sukhoi fighters, which now form a significant portion of the Indonesian Air Force.

Other countries with immediate security needs include Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, Ukraine, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Colombia.

Countries do not usually change arms suppliers overnight, but when faced with ongoing operations or instability, governments under pressure choose to procure equipment quickly.

For China, which places no restrictions on end use of its equipment, filling orders that stem from immediate security needs presents opportunities for valuable follow-on contracts for support and munitions.

Defense Market Opportunity Space for Chinese Arms Exports

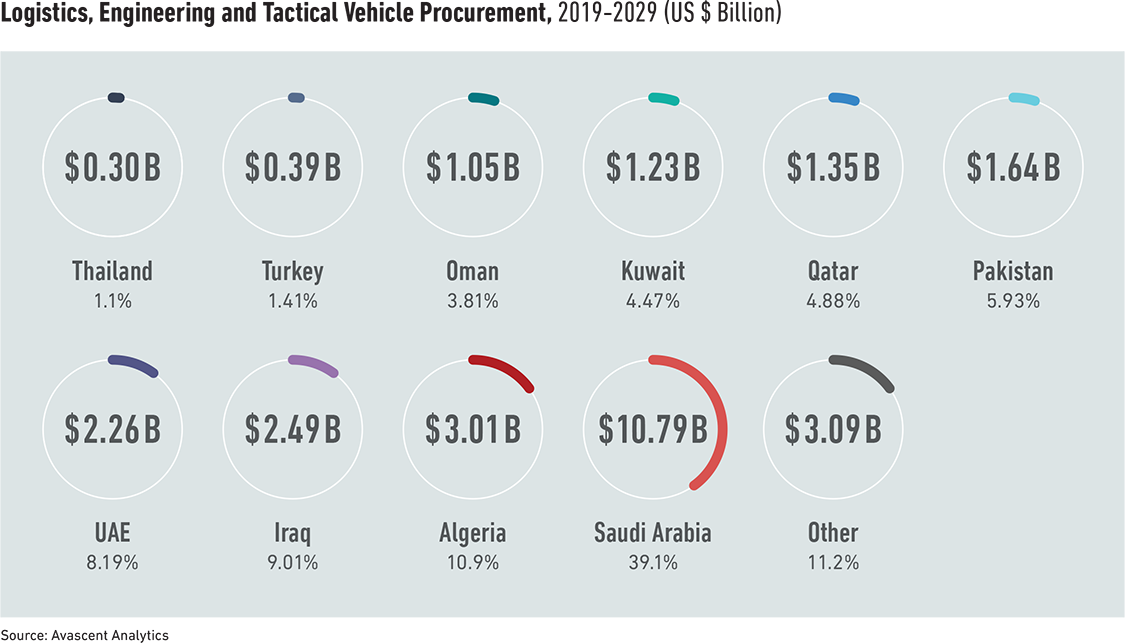

While it is easy to focus on the sale of high-end weaponry, militaries require more than just firepower and cutting-edge technology.

Less glamorous systems such as logistics vehicles and supply vessels have the benefits of being both necessary parts of any force, and devoid of the integration, interoperability, and operational security obstacles that trail higher-end systems.

These market segments, when combined with Belt and Road Initiative deals, may be some of the easier ways for China to break into the European and NATO market.

While such sales individually represent small parts of the market, they are part of a broader foreign policy strategy linked to other economic deals like the Belt and Road Initiative.

The sheer volume of logistics vehicles and equipment alone represents $26 billion of opportunity space over the next decade.

Chinese C2, communications, or weapon systems,

eliminating a major interoperability barrier"

Some NATO members face fiscal issues and defense budget limitations, but still need lower-end capabilities to ensure continued performance of daily operations.

Such lower-end offerings would not necessarily rely on Chinese C2, communications, or weapon systems, eliminating a major interoperability barrier. NATO members who are facing limited budgets but have been amenable to the Belt and Road Initiative include Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania.

Limited funds directed toward procurement and maintenance of more expensive high-end systems like the F-16V crowds out spending on lower-end systems like logistics and tactical vehicles, making less expensive Chinese arms exports more attractive.

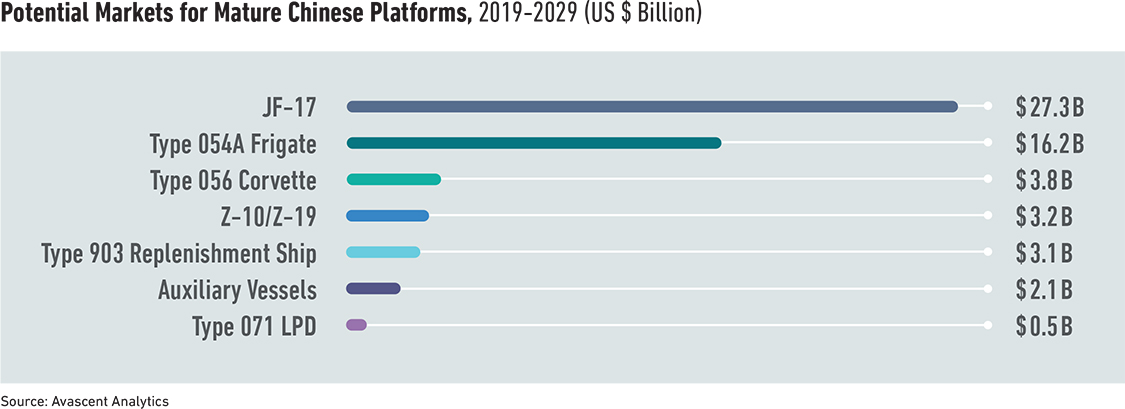

As the PLA modernizes and introduces increasingly advanced systems, Chinese arms exports will include more advanced products. Several long-established platforms with export versions that have not yet won many orders but could be competitive include the

- Z-10 attack helicopter,

- the Z-19 reconnaissance/light attack helicopter,

- Type 903 replenishment ship,

- Type 054A frigate, and

- the Type 071 landing platform dock.

Future acquisitions that these platforms could compete for add up to more than $60 billion over the next decade.

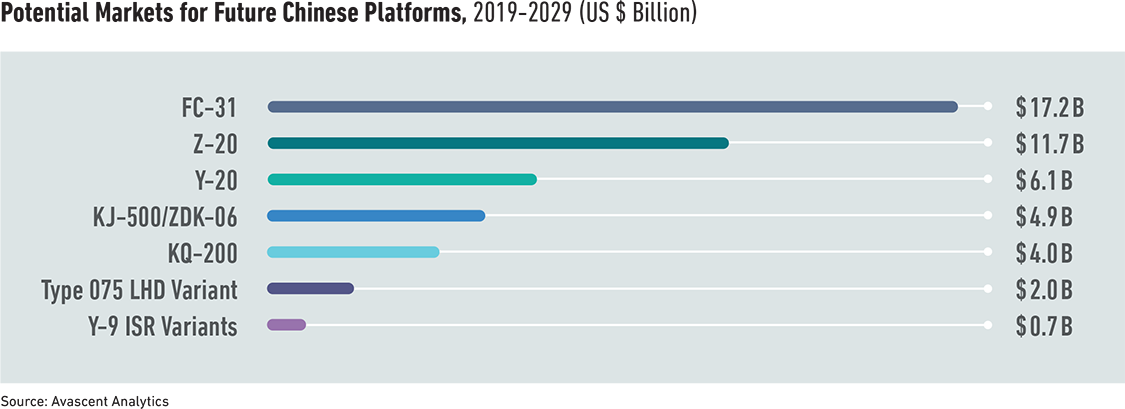

Newer platforms that have either very recently entered service, or have yet to enter service, that could potentially see export versions within the next 10 years include smaller variants of the

- Type 075 LHD,

- the Soaring Dragon HALE reconnaissance drone,

- the Y-20 strategic transport,

- the Z-20 utility helicopter, and

- the FC-31 stealth fighter.

These platforms open another $46 billion over the next decade in future defense acquisitions, allowing China to compete in new segments of the defense marketplace and broaden the competition to traditional arms exporters.

Future Market Footholds for Chinese Arms Exports

The 70th anniversary PLA parade brought into focus an array of systems recently fielded or currently in development, providing a glimpse into what the Chinese defense industry may be capable of offering in the future.

Of particular interest were advanced unmanned systems, the DF-17 hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, a number of long-range cruise and ballistic missiles, and several types of electronic warfare (EW) vehicles.

While China has exported long-range missiles and unmanned systems in the past, the potential export of EW systems represents a relatively new set of markets that China can now serve, presenting a significant opportunity for countries that may not be able to afford expensive Western EW systems, or who cannot import them due to Western unwillingness to sell such sensitive equipment.

Exporting systems with such advanced capabilities to friendly countries would certainly raise China’s technological profile globally, but it would also present significant threats to any countries that stand against one of China’s partners.

The market clearly exists for long-range strike capability, whether that takes the form of long-range land-attack cruise missiles or ballistic missiles. Countries like Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt maintain ballistic missile forces, while other regional powers such as Qatar and the UAE prepare for potential conflict with their neighbors through the purchase of long-range land attack cruise missiles.

The emergence of the DF-17 and other hypersonic weapons raises the prospect that countries currently possessing long-range cruise and ballistic missiles would replace them with more advanced hypersonic weapons in the future.

As for unmanned systems, China has already expressed willingness to transfer the technology needed for other countries to begin building their own.

While Chinese arms exports will not include the most advanced and sensitive systems, even downgraded versions of some of the unmanned systems on parade, like the ASN-301 loitering munition or the FX500 high speed reconnaissance UAV, would provide a major technological boost to a recipient country’s armed forces and industrial base.

In the coming decade, Western and Russian defense suppliers are likely to remain the dominant players in the global defense market.

However, budget and fiscal pressures, local defense industrial interests, defense supplier diversification, and immediate security needs can open sectors of the defense market that have been historically dominated by Western firms to increasingly capable Chinese competitors.

Western defense firms should remain mindful of the unfavorable budgetary and political factors at play within customer countries.

While countries rarely switch defense suppliers for a single reason, recent history suggests that there are many countries that face a range of budgetary and political issues that can combine to make Chinese arms exports more attractive.

Failure to offer cost-competitive solutions or sufficient local defense industrial incentives can open footholds in the Western-addressable defense market for Chinese firms.