Poland’s Balancing Act: A Briefing for the Defense Sector

This white paper was originally published as a two-part piece in Defense Industry Daily.

Russia’s troubling regional ambitions have added urgency to Poland’s $44 billion military modernization and efforts to build a more capable indigenous defense industry.

Against that backdrop, the nationality of the winners of three key upcoming procurements, to be decided in the next 12 months, will set the tone for Poland’s defense relations with the US and Europe over the remainder of its 10-year modernization program.

This is a pivotal year for the Polish defense market. Russia’s actions in Ukraine have underscored the urgency of Poland’s $44 billion military modernization program, and accelerated planned purchases. Critical defense procurement decisions will be made in 2014, testing the government’s ability to successfully manage big international tenders that pit Americans against Europeans. This year will also see the implementation of the country’s highly ambitious plans to consolidate most of its domestic industrial base under one roof, with significant implications for foreign suppliers seeking industrial arrangements with local partners.

Naturally, foreign companies are eager to secure a share in Europe’s most promising defense market. To compete effectively, defense primes and their subcontractors need to understand the financial, industrial, and political landscape they face in Poland.

The Polish Opportunity

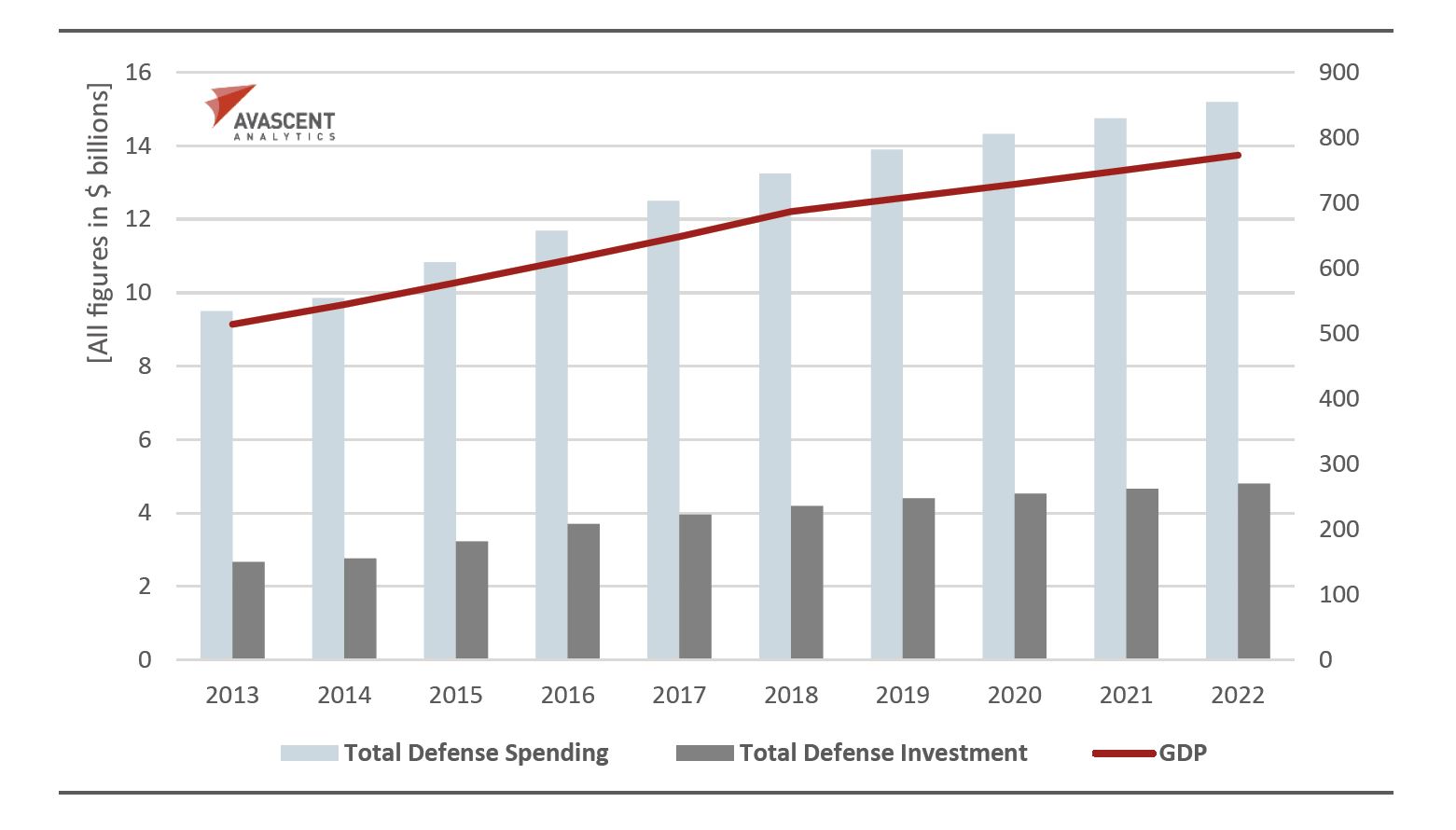

At PLN 32 billion ($10 billion), Poland’s current defense budget is a fraction of Europe’s biggest spenders, but outlays are set to grow faster than in any other country on the continent. Poland is on a path to overtake Spain and the Netherlands in total defense spending in the next two years. (In terms of pure defense investment, Poland already ranks fifth behind the UK, France, Germany, and Italy.) Poland has committed to maintaining its defense budget at no less than 1.95% of the previous year’s GDP, a level currently met or exceeded by only two other European NATO members: the UK and Greece. The Polish economy, now the sixth-largest in the EU, is also among the healthiest. It survived the global financial crisis and eurozone recession remarkably well, and GDP is estimated to grow in real terms by 3.4 percent next year, compared to the EU’s 2-percent average. Poland’s long-term growth is underwritten by the country’s growing exports, strong foreign investment, and some €106 billion in EU funds to be allocated in 2014-2020.

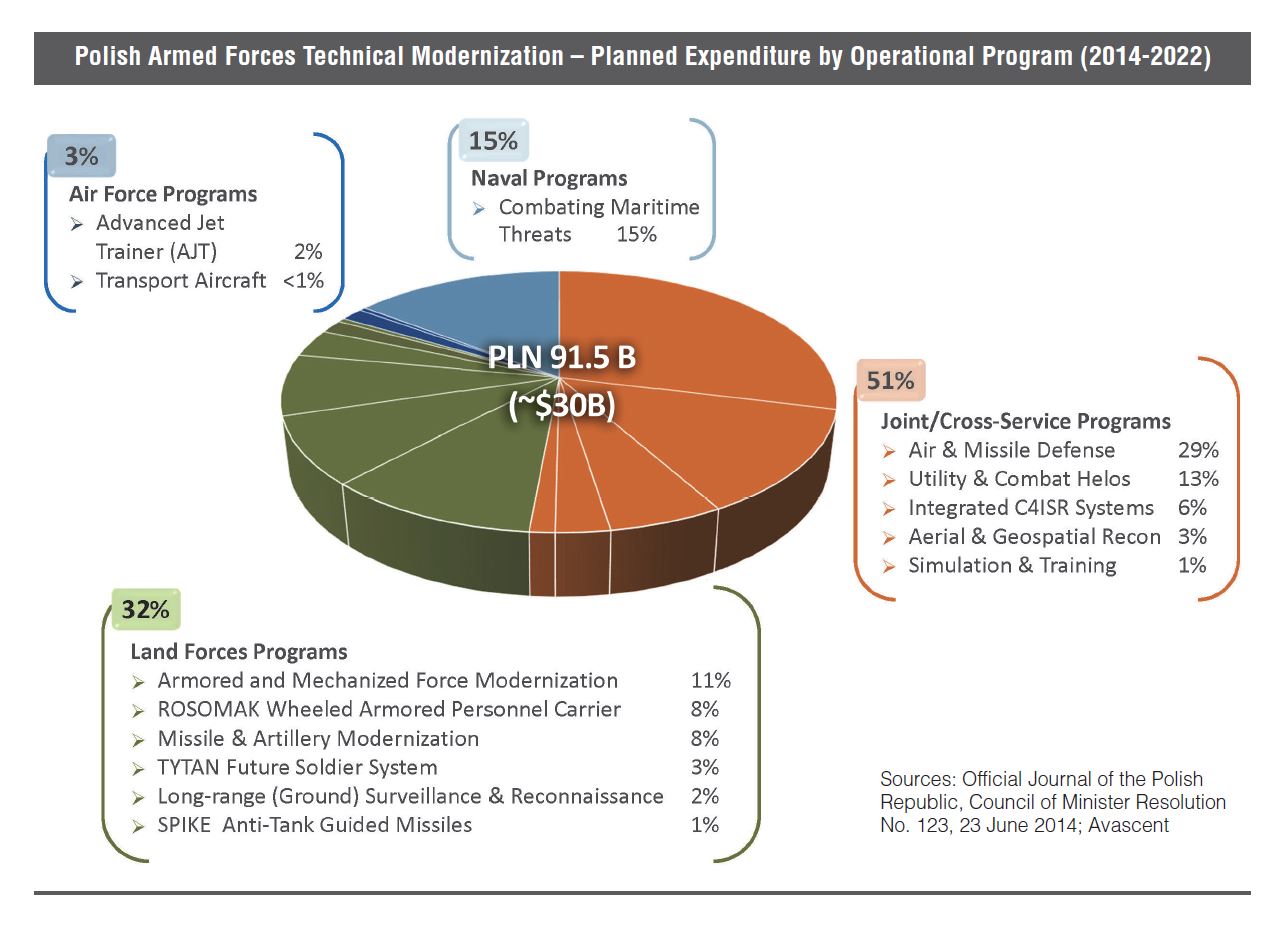

Poland’s TMP is highly ambitious in both scale and scope. Valued at about PLN 131.2 billion ($44 billion), the ten-year program touches on every aspect of the country’s defense apparatus.

Poland’s 2013-2022 Technical Modernization Program (TMP) is highly ambitious in both scale and scope. Valued at about PLN 131.2 billion ($44 billion), the ten-year program touches on every aspect of the country’s defense apparatus. Weapons procurement accounts for 70% of the total, comprising 14 different operational areas. At the beginning of the TMP, Avascent estimates that the Polish defense market was worth some $2.7 billion. This annual figure, which comprises all defense investment and excludes spending on personnel and ongoing operations, is expected to grow to $4.8 billion by 2022. While the Ukraine crisis is unlikely to prompt any further boost for Polish defense spending, it should ensure the planned modernization is kept largely on schedule, and even hastened in select capability areas like attack helicopters.

In sum, the size of the opportunity, combined with solid economic fundamentals and an enabling security environment, makes Poland one of the most attractive defense markets for firms looking to improve their top line with exports.

Polish Partners: The Industrial Angle

Poland’s military modernization program is closely intertwined with the government’s bold plans for developing its defense industrial base. While open competition and formal tenders have become the standard in large-scale contracts, industrial participation has become a key criterion in the selection of foreign bidders.

All government procurements must comply with the country’s Public Procurement Law (PPL) as amended in 2013 and consistent with EU regulations. Where procurement is exempt from the PPL because of national security interests, offsets under the New Offset Act of June 2014 may apply (formally the EU bans all types of offsets because they contravene internal market rules). In reality, however, industrial participation known as “Polonization” has supplanted offset rules, with 25 percent often seen as the minimum threshold for Polish participation in the production process—be it in the form of significant subcontractor work, local footprint, or working through a local partner.

In the land systems sector, Polish industry typically takes the lead, sometimes working under license (e.g., the Rosomak APC, produced by WZM under license from Finland’s Patria) or in close collaboration with a foreign supplier (e.g., PHO and BAE Systems partnering on the development of a tracked platform based on the Swedish CV90 IFV design). Polish industry was upset when the government opted to buy 119 Leopard 2A5 tanks from the German army, instead of paying for a new-design Polish option, but Germany’s extremely low price was an offer they could not refuse. In the air, missile and naval domains, by necessity, foreign primes remain in the lead, but local industrial content can be the determining factor in procurement selections.

Polonization is designed to strengthen the country’s defense industrial capabilities and key competencies in areas consistent with the TMP. This is not unlike the implicit or explicit policies of other European countries. The UK’s 2005 Defense Industrial Strategy identified 12 sectors where the government seeks to retain sovereignty and “operational independence.” However, contrary to the UK and other countries in Europe, Poland’s defense industrial base remains both fragmented and largely inefficient.

The pending far-reaching consolidation of the Polish defense industry under PGZ (the Polish acronym for “Polish Armaments Group”) is intended to address these shortcomings—a move fraught with uncertainties for both local players and foreign partners.

Registered formally in late 2013, PGZ obtained control of 17 entities in May and is now entering the critical second stage of the consolidation process. By the end of the year, PGZ should see the transfer of shares from companies belonging to PHO, or Polish Defence Holding, the country’s largest defense company and itself the recent result of a merger of some 40 entities. PGZ will ultimately comprise at least 30 companies, previously controlled by the MND, the State Treasury and the Industrial Development Agency, a joint stock company owned by the Treasury and responsible for implementing state industrial policy. To be sure, greater scale will not make Polish industry more competitive overseas nor will integration automatically ensure improved efficiency at home. The integration of so many disparate state-run firms presents an organizational, and political, nightmare.

The greatest risk lies in the execution of such an ambitious industrial restructuring, even one based on a sound underlying strategy. Recent history makes this clear. The government’s previous plans to partially consolidate and privatize the defense sector (under its Strategy of Consolidation and Support of Development of Polish Defence Industry in 2007-2012) proved impractical within the original timeframe, and plans to merge Bumar (since renamed PHO) with Huta Stalowa Wola had to be scrapped. Why should setting up PGZ be any easier or more successful? It also remains to be seen how the transfer of PHO minority shares to PGZ will affect other companies, notably Gdynia-based radar company Radmor, controlled by Poland’s largest privately held group, WB Electronics.

The government’s evolving thinking on industrial consolidation has significant implications for foreign players and international partnerships.

The government’s evolving thinking on industrial consolidation has significant implications for foreign players and international partnerships. It is unclear how PGZ will operate as a whole, particularly given historical rivalries among some of its constituent elements, what degree of autonomy will be left to individual entities, or how consolidation of capabilities within the group and the creation of centers of competence across the broader industrial base will occur over time.

Given the requirements for Polonization and industrial participation, foreign suppliers can ill afford ignoring these ongoing developments within the Polish defense industry. Even the most tactical pursuit, let alone long-term success, in the Polish defense market requires proper due diligence in the selection of partners and close monitoring of the government’s evolving defense industrial plans.

No Simple Choices: Purchases as Geo-Strategy

For the past decade, Poland has thought about its future as a nation aligned with both America (through NATO) and Europe (through the EU). Yet Poland’s defense modernization may now force it to pick sides, in a sense, between American and European defense industrial partnerships. These industrial choices will force them to consider near-term jobs and investment, long-term opportunities that can help Poland maintain a strong national defense sector, and the uncertain quality of security guarantees on both sides of the Atlantic.

Poland sees the European strategic environment through a unique perspective. Historically, the scars of the 20th century linger. Geographically, it is the largest border country in the eastern part of the EU. Vladimir Putin’s ambitions add urgency to Poland’s modernization plans, and indeed validated the country’s often-alleged “paranoia” about Russia. As Poles often like to say, echoing Joseph Heller’s memorable phrase in Catch-22, “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you.

In that kind of environment, outside events and near-term decisions may have long-term consequences.

US responses to the crisis in Ukraine, including the dispatch of US F-16s to Poland shortly after Russia’s intervention in early March, and the $1 billion European Reassurance Initiative announced by President Barack Obama in early June, have been predictably faster and more forceful than Europe’s. That doesn’t change the revelations that senior Polish officials have lost a great deal of trust in the United States, but it may help.

Poland will have to juggle military capability requirements, industrial imperatives, and geo-strategic considerations as it seeks to complete three of the largest defense purchases under its modernization program in the coming 18 months.

Meanwhile, the EU sanctions on Russia that took effect on August 1 are far more extensive than previous restrictions. On the other hand, it took the EU fully five months to reach this modest point, following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, and events continue to unfold in the Ukraine. France’s dogged refusal to cancel delivery of the first of two Vladivostok Class amphibious assault ships sold to Russia (first delivery is expected in October) could ultimately harm French industry in Poland, despite strengthened bilateral ties over the past couple of years.

None of this eliminates the need to buy the best military capability, even if other considerations sometimes relegate it to one factor among many. Polish history does not suggest a tremendous margin for error, and Poland’s terrain, geography, and plausible threats will make some platforms better than others at meeting the country’s needs.

In sum, Poland will have to juggle military capability requirements, industrial imperatives, and geo-strategic considerations as it seeks to complete three of the largest defense purchases under its modernization program in the coming 18 months. The bad news is that those considerations sometimes work at cross-purposes.

A Looming Transatlantic Battle

Up to PLN 3.5 billion ($1.2 billion) are to be spent this year on military equipment approved under the multi-year TMP. According to the latest government estimates, this figure will increase to PLN 7 billion by 2016, with the remaining PLN 75.6 billion to be spent in 2017-2022. Of the PLN 91.5 billion allocated for 2014-2022, three procurements to be decided within the next several months will consume some 40 percent of the total.

All three will pit major US and European companies against each other, creating something more than a typical industry showdown. The contracts will be viewed as Poland shifting its defense posture toward European industry and its attendant alliances – or away from it.

US-European rivalry for the Polish market will be most intense within the broader air and missile domain. Poland’s military modernization also features several programs in the land and naval domains, but individual competitions tend to be smaller in value, or offer fewer inroads for American firms. Naval competitions primarily draw European bidders, while land systems programs typically involve leading roles for Polish industry.

Medium-range air defense system

The PLN 16 billion “Wisła” (or Vistula) program is part of a PLN 26.6 billion ($8.5 billion) multilayered “Shield of Poland” air defense system, and stands as the single largest near-term program. It will be decided in coming months between the two remaining bidders: Raytheon and Eurosam (a Thales/MBDA consortium). Wisła involves 6 batteries of missile systems with a range of over 100km, with deliveries scheduled in 2017-2022.

Out of a total of 14 potential contractors from seven countries, four were initially invited to engage in talks: one US (Raytheon), one European (Eurosam), one involving US-European cooperation (MEADS International, led by MBDA Germany in partnership with Lockheed), and the Israeli government representing various Israeli companies. The MND’s June 30, 2014, announcement that it had down-selected Raytheon and Eurosam surprised many observers. This was a near-complete reversal of fortunes from earlier this year, when Raytheon was thought to be in a losing position against the MBDA-backed MEADS and Eurosam SAMP/T teams.

In announcing its decision, the MND decided to prioritize project risk and time to deployment. It adopted three main criteria: the system had to be operational; it had to have been adopted by a NATO country; and it had to offer significant participation for Polish industry. Raytheon’s offering is now seen as a lower-risk, quickly deployable solution that easily meets the first two criteria, after their adoption effectively excluded both MEADS and David’s Sling.

Industrial participation remains an important factor, possibly the most important. Eurosam’s comprehensive offer is balanced against Raytheon’s ability to offer export opportunities within its wide customer set. Both bidders will have an opportunity to improve their offers, and up to half of the contract’s value could wind up with Polish firms.

The choice of Poland’s newly consolidated PGZ as a partner is a given for both Wisla bidders, and PGZ is also expected to play a prominent role in the medium-range Narew air defense program. Engagement across the broader Polish defense industry, such as the recent LOI signed between Raytheon and TELDAT, should further strengthen each side’s industrial offer. Raytheon has focused its cooperation on radars and command and control systems. Eurosam’s focus remains to be seen.

Operationally, integration into NATO’s Active Layered Theatre Ballistic Missile Defense (ALTBMD) is guaranteed with both bids, but cost and access to future upgrades could prove critical in the Polish government’s decision. That decision’s scheduling ensures that it will land in conjunction with key upcoming missile defense procurements by two other NATO members, Germany and Turkey. Taken together, these three decisions have the potential to substantially reshape NATO’s missile defense architecture.

Medium-lift utility helicopters

The other major transatlantic contest, worth about $3 billion, involves the procurement of 70 helicopters (48 multi-role transport, 16 Search and Rescue/Combat SAR, 6 anti-submarine) to be deployed throughout the Polish military. A winner will be selected by the end of the year, ahead of the announcement on the missile defense competition, with the first aircraft due to enter service in 2015.

Three bidders are competing: two European and one American. Airbus Helicopters’ EC725 Caracal (Super Cougar), AgustaWestland’s AW149, and Sikorsky’s S-70i Black Hawk have until September 30 to respond to the RFP issued in early June.

The S-70i would seem to have the advantage both operationally (in meeting the anti-submarine capability requirement) and in terms of industrial footprint (leveraging its PZL Mielec subsidiary, which serves as the global final assembly center for the S-70i). AgustaWestland will match Sikorky’s in-country presence by leveraging its own PZL Swidnik subsidiary, and Airbus Helicopters plans to use a teaming arrangement with Heli Invest/WZL-1 to make up for its weaker local footprint.

Any shortcomings in current capability by either European bidder will have to be offset by a better price offer, and a more expansive industrial partnership package.

Attack helicopters

The tender for the “Kruk” (Raven) program was originally scheduled to be launched in 2018, with delivery starting in 2020. In response to recent developments in Ukraine, the Polish government has decided to accelerate the timeline. The procurement of 40 attack helicopters, up from 32 at the start of the TMP, will replace the Polish land force’s fleet of 29 Mil Mi-24D/Vs. Poland’s military views this program as particularly critical to the nation’s defense, given the country’s wide open, rolling landscape from East to West.

Ten bidders have reportedly responded to the August 1 RFI deadline, and once again US and European suppliers appear to be the strongest contenders for this $1.5 billion buy. Boeing (AH-64E Apache) and Bell/Textron (AH-1Z Viper) represent the US side, while AgustaWestland/Turkish Aerospace Industries (T129 ATAK) and Airbus Helicopters (EC665 Tiger HAD external link) are leading on the European front. It is unclear whether Sikorsky has offered a S-70i with their Level 2 or 3 Battlehawk kits, but the number of respondents and Sikorsky’s bids elsewhere indicate that this is possible. The bidders’ Polonization approaches are also unknown, with key industrial partnerships likely to become known in coming months.

An award decision is expected sometime in 2015, most likely after the Wisla program’s winner is announced, making this the last pick of the three tenders. That could make Poland’s Raven a more politically charged competition than might normally be the case.

What Now, What Next?

Poland faces a significant challenge as it moves ahead with its next three big-ticket purchases. All three programs are critical to the country’s national security, but Polish doctrine and threat assessment should dictate different strategic weightings.

The need to stay within the TMP’s fixed budget may also shape the government’s options. An earlier competition this year for advanced jet trainer (AJT) aircraft was awarded to Alenia Aermacchi (like AgustaWestland, a subsidiary of Italy’s Finmeccanica), who offered eight of its M346 jets and support at the bargain price of PLN 1.186B ($390M). The bids for BAE’s Hawk and LM/KAI’s T-50 were 46% higher and 50% higher than the MND’s PLN 1.2 billion cap, respectively. Many outside observers saw this cap as a highly unrealistic target, given the inclusion of 30-year sustainment support in the bid request. A repeat of this scenario for a strategically important buy would have much more serious consequences.

We believe that the most likely outcome of the three upcoming competitions will be a 2:1 split in favor of one side, rather than a sweep. One plausible scenario would see Poland buy a mix of US and European helicopters, and a US air and missile defense system.

One plausible scenario would see Poland buy a mix of US and European helicopters, and a US air and missile defense system.

Within Europe, a parallel game of musical chairs is underway across the TMP, although even here the spoils (spread across air, land, and naval requirements) should be shared, however unevenly, among Europe’s four largest national industrial bases, plus the Scandinavian countries.

While in theory these upcoming Polish military acquisitions are not linked, their combined outcome will send a political signal to both sides of the Atlantic. The decisions will also determine the degree of the country’s integration into, and acceptance by, the rest of Europe’s defense industry. Under these circumstances, we believe that integrated management would offer Poland clear benefits. The Polish government could afford to make trade-offs among programs to facilitate planning across the entire TMP, while remaining within the total allocated budget. In addition to stretching the delivery period for certain systems, for example, the MND can opt to invest less in one area to pay for additional capability in a more strategic area.

All this should set the stage for other medium-term procurements that will further test Poland’s relative penchant for weighing US and European systems against each other, including medium-heavy lift aerial transports, various C4ISR programs, and, even further down the road beyond the TMP, next-generation fighters.