Space SPACs – Valuation in Zero-G

Avascent and Jefferies, leading strategic and financial advisors respectively in Aerospace, Space and Defense, collaborated on this edition of Avascent Apogee.

In September 2008, Iridium did something no space company had done to date – it announced a deal to raise $324M through a merger with GHL Acquisition company, and in doing so, became the first company to dawn the title “Space SPAC.”

Though the fundraising approach took over a decade to catch on, SPACs have since exploded in popularity, with more than $83 billion raised in 2020 compared to merely $14 billion in 2019.

Q1 2021 in particular saw a boom in Aerospace & Defense SPACs raising over $11 billion from space to eVTOL companies, behind Automobile components & Software sectors at over $20 billion with TMT (Tech, Media & Telecommunications) unsurprisingly leading overall transaction volumes. Much ink has already been spilled to explain the phenomenon, so how does this apply to the space industry?

SPACs are particularly suited to markets with long-term investment plans. Investor pitches can focus on projected future revenues and build hype around companies with limited current revenues that would typically not be able to go through the traditional IPO route.

Low interest rates have made longer-duration investments even more tenable, and the New Space industry checks all the boxes.

The SPAC market is increasingly pulling forward public offerings in place of late-stage venture capital raises, providing the pivotal tranche of investment that funds the final stage of cash burn in capital-intensive industries like space.

Notably, SPACs offer capital-intensive space businesses:

- Rapid access to highly sought-after liquidity;

- An alternative to late stage venture capital that accelerates progress towards achieving a first mover advantage, and;

- Exposure to retail investors (who up until now had a limited choice of publicly-listed “space” companies)

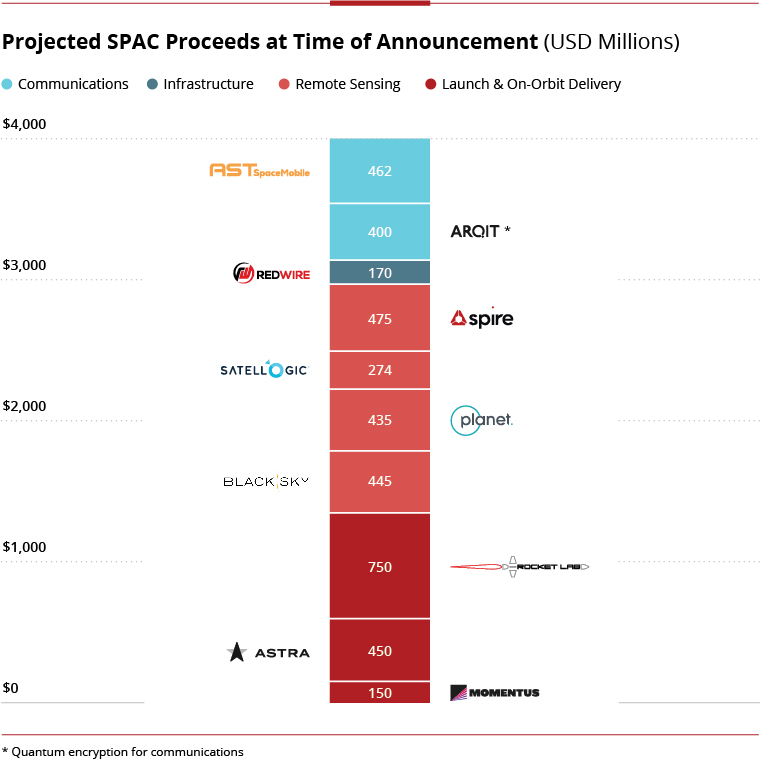

Recent high-profile “space SPACs” have been able to raise over $4 billion, based on aggressive growth projections and a rapidly expanding addressable market.

Only a few of them have “de-SPACd” and are currently listed (AST Space Mobile, Astra Space, and Spire) with most companies expected to do so by Q3 2021.

Pricing the Future for Space SPACs

There is no free lunch in capital markets. Given that space SPACs offer high return opportunities, they consequently carry notable risks:

- Will the technology work?

- Will the market materialize?

- Can management deliver on the business plan?

- Can the cost curve continue to come down as it has historically?

Other questions abound.

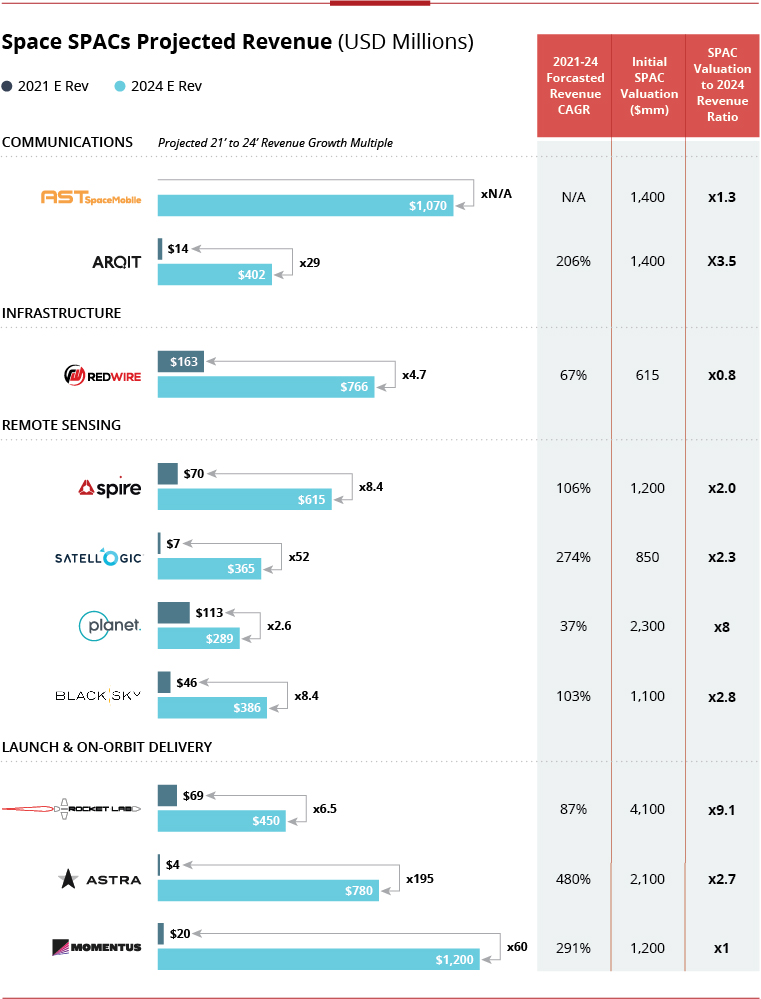

And with many space companies still pre-revenue but with potentially parabolic growth curves, traditional valuation methods (trailing EBITDA multiples and DCF) rarely apply. Instead, valuations are largely anchored on forward year multiples of revenue and EBITDA.

By anchoring on these forward metrics, space SPACS offer a deal to investors – “if we hit our projections we’re a bargain, but you have to trust us.”

For instance, BlackSky’s deal with Osprey Technology Acquisition Corp. was struck at a $1.1 billion, or roughly 6.3x 2024E EBITDA. Compare that with Maxar, which recently traded as high as~12x 2021E EBITDA.

If BlackSky’s forecasts are realized it’s a steal at the current value, even if it appears rich based on next year’s financials.

As the number of publicly traded pure-play space companies proliferate and successfully de-SPAC, they begin to establish public market values for subsectors where none existed before (e.g. small launch, proliferated constellations, infrastructure, and payloads).

RockletLab’s announced deal value of $4.1 Billion is 9.1x 2024 revenue – that may feel heady until you compare it with Virgin Galactic at 19.4x. The “right” multiple isn’t obvious.

One of the pillars of valuation is comparable companies analysis (“comps”) – and we are witnessing entirely new comp sets being built across the new space ecosystem.

Finally, private, late-stage venture funding rounds can also serve both as a reference valuation for SPAC deals and as a competitor to SPAC exits (e.g. Firefly and Relativity, two emerging launch companies that recently chose attractive private financings rather than accessing the public markets).

The aforementioned valuations, based on projected future revenue – and often immature markets – represent significant year-over-year growth.

For many, this will look like the old “if you build it they will come” adage. But to answer one adage with another, “not all SPACs are created equal.”

Different Paths to Value for Space SPACs

The space value chain encompasses a host of overlapping business models. Space SPACs range from B2B satellite component manufacturers and B2G satellite integrators, to B2C communications and human spaceflight providers. Each offering its own addressable market, competitive dynamics, and value proposition.

Historically, B2G space companies – especially integrators – have seen relatively low EBITDA margins in the 10-13% range, while successful B2B component providers can see margins in the 15-30% range. And new models continue to emerge.

Space infrastructure as a service is one that aspires to apply the SaaS business model to space in order to reduce customer friction and achieve higher margins.

One notable example is on the ground side where companies such as AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Atlas Space are marrying ground infrastructure and data backhaul with cloud storage and processing.

Launch has always been delivered “as a service,” but considering that the vehicle was discarded after each launch, it was more akin to a product sale.

But with reusable launch now a reality, it too is falling into the infrastructure as a service model, with launch vehicles no longer booked as COGS, but as depreciable assets.

The current Space SPACs are not only pursuing different business models, many are targeting different markets entirely.

Most of Redwire’s portfolio companies sell components to traditional space primes and the US Government, but they also have innovative in-space 3D printing capabilities that could help push the boundaries of in-space manufacturing.

Spire sells data solutions to global governments and commercial customers and has recently expanded into space infrastructure as a service. AST, taking yet another approach, is targeting Telcos to extend mobile phone service to the end-user.

Asking the Right Questions

Given the degree of variation, it is no surprise to see a wide range of valuations across companies. Yet they all have one thing in common – dramatic growth projections.

With more space SPAC announcements seemingly inevitable, and so much of their valuations tied to expectations, it is crucial for investors to be able answer the following questions before placing bets:

- How is the target market(s) currently served, i.e., is there an established industrial base, or is this a new market?

- Is the target market(s) large enough (or growing fast enough) to support the company’s growth projections?

- Are there reliable anchor customers (such as the US Government) who can underwrite the development risk and bridge the gap to broader market maturity?

- Does the offering address multiple user communities, e.g., national security, civil or commercial?

- Does the target’s business model support its EBITDA margin projections when benchmarked against peer industries?

- Is the company’s solution truly differentiated from established or in-development peers?

- How well positioned is the management team to execute its business plan?

Subscribe to the Avascent Apogee

We invite you to subscribe to the Avascent Apogee – Insights delivered to your inbox on critical issues shaping the Space industry’s future.