The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle East Defense Spending

Projecting the impact of COVID-19 on Middle East defense spending in the near- and mid-term is made challenging by the diversity of countries found in the region.

This includes not just the wide disparities in economic and social makeup of countries that stretch from North Africa to the Iranian border, but also the strategic circumstances they face. While the coronavirus makes little difference in whom it infects, the ways in which governments across this turbulent region will respond and recover may vary widely.

This paper is the latest in a series by Avascent Analytics that explores how the COVID-19 pandemic will reshape the global defense market. To be sure, the public health and economic effects of the crisis are not yet fully understood. The pandemic remains ongoing, and no one yet knows precisely how deep an economic shock it will have. This makes projecting outcomes a highly fraught project.

Nevertheless, the following aspects and associated questions have been considered in this series, such as:

COVID-19 Across Multiple Regions of the Middle East and North Africa

With over 300,000 cases of COVID-19 reported by late May, the Persian Gulf has been one of the hardest hit regions in the global pandemic.

As a share of total population, the infection rate among Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar exceeds those even of countries like Italy, Spain and the United States, which have characterized the worst of the coronavirus pandemic. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) seem to have fared better than many of their neighbors but have still seen over 100,000 COVID-19 cases as of May 25, 2020.

Countries on the Arabian Peninsula already had experience in dealing with flu-like epidemics. In 2012 the coronavirus Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) appeared in Saudi Arabia.

While people in 27 countries were ultimately contaminated with MERS, 80% of cases were concentrated in Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom registered the highest death toll, with more than 500 fatalities.

When reports emerged of fast-spreading COVID-19 in early 2020, Saudi Arabia, followed by others, was among the first to close its borders, even in the absence of in-country confirmed cases. Across the region, strict lockdowns, curfews, and drone patrols were quickly put into place.

Conversely, countries in the Levant and North Africa appear to have been affected to lesser degrees by the COVID-19 pandemic. Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, most with larger populations than the major Arab states of the Persian Gulf, have thus far seen infection rates well below those in the Persian Gulf.

The same has been true of Israel, Jordan and Lebanon. In Libya, Syria and Yemen, gauging the state of the COVID-19 pandemic is made challenging by the limits of data transparency that accompany active conflict zones. (Indeed, beyond COVID-19, data limitations due to low government transparency are nowhere more challenging for defense spending analysis than in the region under review here.)

A notable social and demographic feature of the Persian Gulf is the heavy presence of foreign nationals among the workforce. More than 70% of UAE’s population is comprised foreign citizens, from workers employed in mega-infrastructure projects and tourism, to expatriates working in the financial and energy sectors.

Qatar, Kuwait and Oman draw on non-citizens for more than half their workforces. The intensity of the coronavirus outbreak among crowded worker dormitories in Singapore illustrated the great risk that this population could bring for further development of the pandemic in the Persian Gulf.

The relatively light impact of the coronavirus on public health (so far, anyway) implies that public finances across much of the Middle East may be spared the worst effects of an economic downturn. This, in turn, suggests that the impact of COVID-19 on Middle East defense spending may be relatively unaffected.

Some aspects Middle Eastern economies may feel the effects of COVID-19 well after the outbreak is well under control. For example, many countries in the region rely heavily on tourism.

Discretionary travel seems likely to be depressed for some time to come, perhaps even for the devout making the pilgrimage to Mecca. However, the role of energy exports in public finance is hard to exaggerate, and oil prices have fallen sharply just as the pandemic has swept the globe.

Energy Exports and Economic Prospects

In early March, just as many jurisdictions around the world were starting to impose restrictions on travel and gathering, Russia and members of OPEC met in Vienna to resolve a dispute over oil production. But the group largely failed to staunch a drop in prices that was larger than any since the 1991 Gulf War.

The battle for global market share, principally between Russia and Saudi Arabia, came as the worldwide economic lockdown sharply curtailed energy demand.

For Saudi Arabia, edging out Russia for market share seemed to justify the “short term pain for long term gain” approach, with the expectation that crude oil prices would eventually rise.

In the interim, Saudi Arabia’s government expects its financial reserves to be capable of sustaining the country’s economy for a couple of years. While Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman aims to reduce the Kingdom’s dependence on hydrocarbon exports under his Vision 2030 initiative, the sudden collapse in oil prices came long before the country had truly diversified its economy.

If Saudi Arabia and UAE have the currency reserves to endure a brief period low oil prices, many other countries across the region may be more vulnerable.

Around the Persian Gulf, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, and Oman are heavily dependent on energy exports to fuel their national economies. In North Africa, the same can be said of Algeria and Libya. (The latter, of course, is locked in a violent civil war.)

Dependence on oil exports for economic growth and government budgets has a direct impact on these countries’ ability to modernize their military forces. Indeed, where many countries’ spending on defense generally tracks with the ebb and flow of GDP as a whole, among oil-rich countries, the price of oil is a far better indicator of their propensity to spend on defense.

Figure 1: Change in the Price of Oil and Change in Defense Spending: Algeria and Saudi Arabia

Figure 1 illustrates that while Saudi Arabia has been able to sustain spending in the face of global economic downturns (as in the 2008-09 financial crisis that arose from the US housing market), its defense spending has been highly sensitive to longer-term ebb and flow in energy prices.

The same should be expected of the rest of the Persian Gulf oil exporters, including:

- Bahrain,

- Kuwait,

- Oman, and

- Iraq

Algeria, also shown in Figure 1, features a defense budget that is similarly linked to oil prices.

Other Sources of Government (and Defense) Finance

Not all countries in the greater Middle East region, of course, are oil exporters. But a few rely on financial support from major oil exporters like Saudi Arabia and UAE.

Egypt, in particular, has benefitted from aid in the form of oil, in-kind assistance, as well as financial grants and loans from Saudi Arabia, UAE, and other Arab states in the Gulf. Belt tightening in Riyadh and other Gulf capitals seems likely to factor into defense planning in Cairo.

But the largest provider of military aid to the Middle East has been the United States. Israel and Egypt are the largest recipients of US military aid. But Iraq and Jordan have also boosted their defense procurement activities with US Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funding.

Figure 2: US Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Support to Middle East Countries

For the most part, this funding seems fairly secure. There are no signs that the United States plans to rethink its longstanding support to these countries. This funding is seen in Washington as key to sustaining an uneasy peace between Israel and its neighbors.

With respect to Iraq, continued FMF funding hinges on continued good relations between the United States and the Iraqi government of the day. Washington has a keen interest in keeping Iraq able to act as an independent check on Iranian regional power.

But it is increasingly clear that politics in Baghdad are strongly influenced by Teheran. Relations between the United States and Iraq have been rocky in the wake of the 2019 US air strike that killed Maj. Gen. Qasem Suleimani, commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

While there is no clear sign of it yet, it seems conceivable that a formal breech between Washington and Baghdad could bring all manner of effects, including a suspension in FMF funding.

East defense spending will take the form of

spending cuts & budget reallocations to fulfill

social & healthcare priorities among a number

of Middle East countries."

The Cost of COVID-19 Response

It is likely that the impact of COVID-19 on Middle East defense spending will take the form of spending cuts and budget reallocations to fulfill social and healthcare priorities among a number of Middle East countries.

As an example, King Mohammed VI of Morocco in March 2020 announced the creation of a $3.2 billion emergency fund to help people thrown out of work by the outbreak. The Egyptian government also set up a multi-million dollar fund to financially support some sectors (healthcare, welfare benefits).

UAE has put into place a rescue plan with tax exemptions and other stimulus to keep the local economy moving. Launched in March 2020, the Dh50.0 billion Targeted Economic Support Scheme (TESS) is aimed at keeping the national economy strong.

This follows financial disturbances in the wake of the 2008 crisis and the UAE government’s bailout of the Emirate of Dubai with an extended loan of $5.0 billion due to high exposures to financial services and debt burden.

As large as these programs sound, it would appear that the cost of coping with COVID-19 among most Middle East countries will be relatively manageable.

To be sure, the public health and economic costs of COVID-19 will be significant, particularly if the global economic downturn persists into 2021 and beyond. But it seems that oil prices will have a more substantial effect on the defense budgets of those countries that spend the most in the region.

The Potential Impact of COVID-19 on Middle East Defense Spending?

From a strictly economic perspective, several alternative hypotheses can be drawn about how this will impact defense spending. At this stage, no one can yet know how dramatic the impact of COVID-19 on Middle East defense spending will be in each country, or the depth and duration of the economic downturn.

Therefore, it seems appropriate to envision a series of scenarios for how defense spending in Middle East and North Africa may differ from our current expectations.

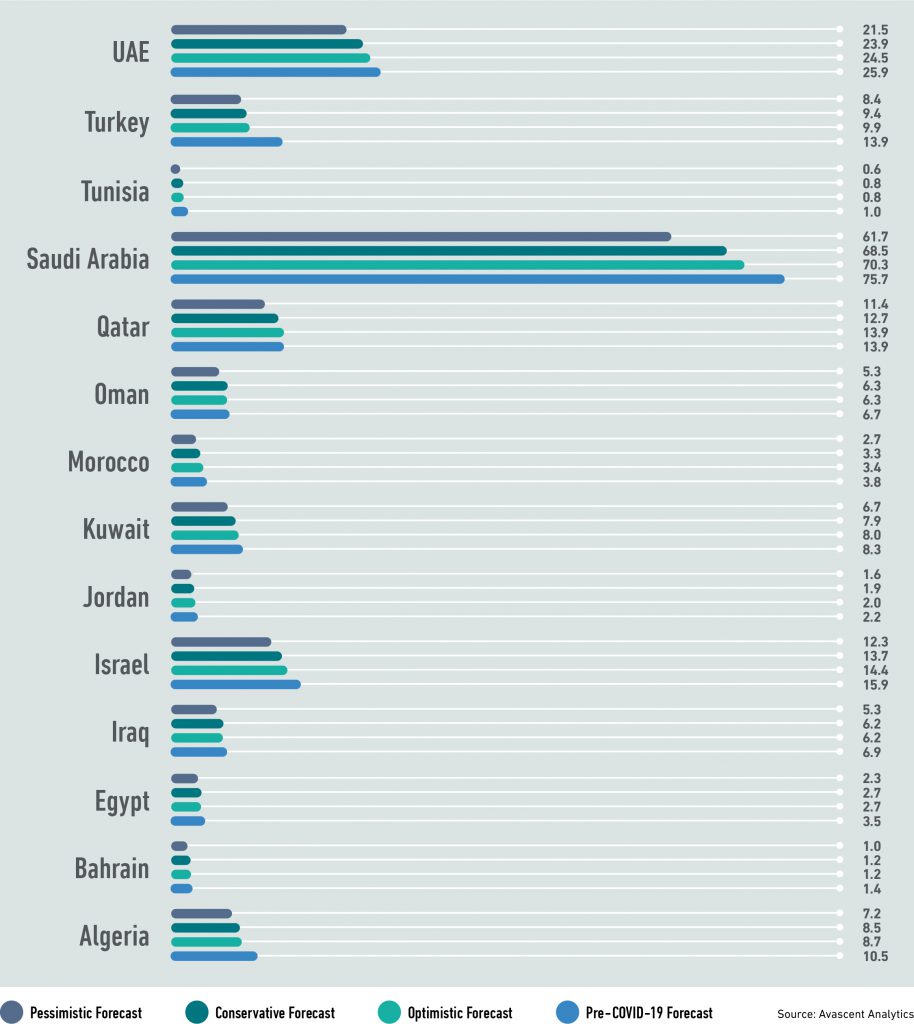

In this regard, figure 3 is an initial attempt to consider these various potential cases for defense spending reductions in the short term. We have chosen the year 2020 as the basis for these scenarios.

Figure 3: Alternative Scenarios for Defense Spending in 2020 (USD Billions)

While some regional economies may suffer severe GDP contractions, with the potential to prompt drastic cuts as shown in the pessimistic forecast, it merits noting that as of late May 2020, no country in the region has formally announced defense spending cuts.

Indeed, more than most, the Middle East and North Africa is a region where perceived threats from both non-state actors and assertive national powers are very high. For all its own problematic dependence on oil revenue and its underlying economic and political weaknesses, Iran remains for many countries in the region a highly visible and active threat.

Conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Libya continue to create instability in the region, serving to exacerbate existing sectarian, ethnic and national tensions. The continued presence of both US and Russian military forces in Iraq and Syria illustrate the immensely fraught condition of Middle East security.

All of this may serve to limit the impact of COVID-19 on Middle East defense spending, even if the region’s finance ministers might prefer otherwise.

All of this suggests that, at least as far as the 2020 budget is concerned, less severe reductions in defense spending may be likely. But the impact of low oil prices could very well drive Persian Gulf states (and perhaps Algeria) to proceed more slowly with prior spending plans in 2020. They may also move more slowly in distributing assistance to regimes like Egypt that have come to rely on their aid.

This creates a potential opening for China, whose military and financial power seems likely to expand in the wake of COVID-19, even if criticism of its early response to the pandemic lingers.

China has grown its defense export activity in recent years, with a handful of major sales to the Middle East, such as CH-4 drones to

- Egypt,

- Jordan,

- Saudi Arabia, and

- UAE

Under the Belt and Road Initiative, China has been drawing on national industries and aggressive financing terms to secure infrastructure and other projects around the world.

Applying this model to defense exports seems likely. The key for China will be to execute sales and still satisfy importers’ rising desire for technology transfer and domestic economic benefits.

Favoring National Defense Industries

This white paper series has made the case that governments are likely to use domestic defense companies as channels for economic stimulus and employment sustainment.

Further, governments are likely to favor acquisition programs and other activities that draw on local sources and workforces and to accept delay and risk among imported solutions. This includes not just capital equipment, but also supplies and materiel needed for operations and sustainment.

This tendency will also feature among Middle East countries, but the geography and scope of Middle Eastern defense industry indicates that these effects will be targeted.

Algeria, Turkey, Egypt, UAE and Saudi Arabia have all made varying degrees of investment in their national defense industries, drawing on a mix of domestic resources, foreign aid, and offset-driven contributions from foreign exporters like the United States, France, and the UK.

As shown in figure 4, some countries in the region are less dependent on foreign military imports than others. In this region, Israel and Turkey lead the way. Avascent estimates that domestic companies are able to serve over 50 percent of both Israeli and Turkish defense acquisition requirements.

Figure 4: Key Parameters Around Middle East and North African Defense Spending

Israel’s access to large FMF allotments is increasingly conditioned on using them to acquire from US companies. The 2016 memorandum of understanding between Israel and the United States increased the 10-year military aid package by $8 billion but set tighter restrictions on Israel’s ability to use these resources on Israeli sources of supply.

So while Israel will continue to draw on US dollars to purchase some platforms (e.g., F-35, KC-46) and other material from the United States, the bulk of its Shekel-denominated budget will remain with Israeli sources, who can supply most of the IDF’s requirements beyond fighter aircraft, helicopters and submarines.

Apart from Israel, no country in the region has created as robust a defense sector as Turkey. The country has developed a defense industry that SIPRI estimates as the 14th largest in the world. Its five leading defense companies collectively employ roughly 18,000 people across a range of sectors, including:

- Shipbuilding,

- Rotorcraft,

- Land vehicles,

- Defense electronics,

- Munitions, and

- Unmanned aircraft

Notably, Turkey has exported drones (sales in Tunisia in 2019) and has been positioning to export helicopters (T-129 offered to Bahrain in 2015) and fighter aircraft (Malaysia as a possible country partner for the TF-X-2020).

Particularly in the wake of Turkey’s apparent expulsion from the US-led F-35 program as a result of Ankara’s insistence on continuing with its deployment of the Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system, it seems likely that Turkey will aim to keep this strategic investment in national sovereign capacity on track.

As part of its Emiratization strategy, UAE has recently spurred the national defense consortium EDGE to reorganize greater competitiveness, and to strike a partnership with Tawazun Economic Council on defense R&D.

Even assuming a downturn in UAE defense investment as a result of lost oil revenue, continued emphasis on this initiative should gain continued support in order to achieve market growth, uphold local employment, and reduce the country’s dependence on foreign suppliers.

Interestingly, some nascent industrial bases in smaller economies are also gaining traction: Tunisia was keen to show in the early days of lockdown its locally designed and built patrol robots by a 100% Tunisian firm.

As part of its Vision 2030 initiative, Saudi Arabia has been organizing to bolster its domestic defense industry. Much of the current Saudi capacity reflects activities created in support of high-end systems imported from the West.

By and large, these are associated with sustainment services for military platforms and other equipment, often in close cooperation with the exporting company (e.g., BAE Systems, Boeing, Lockheed Martin and most recently Oshkosh).

Keeping Saudi citizens employed – and non-hydrocarbon industries growing – seems likely to benefit companies operated in cooperation with foreign primes, such Al Salam Aerospace (involving Boeing) and Overhaul and Maintenance Company (with BAE Systems).

Prioritization Amid Tighter Budgets

While threat perceptions and ongoing tensions remain high in the region, some slackening of defense spending seems very likely across the region in the near- and mid-term. As noted, this may hinge in part on how rapidly oil prices rebound.

But assuming they remain depressed for the foreseeable future, some major procurement programs among oil-dependent customers will take a hit in the short term.

COVID-19 may delay significantly future large-scale programs such as combat aircraft and surface combatants. While these often enjoy powerful constituencies, the scale of investment and timelines they involve make delay an easy card to play.

But requirements in other areas, whose criticality has been demonstrated clearly in recent years, stand a better chance of coming to fruition in the near-term. These include air and missile defense, counter-drone solutions, border security, and cyber.

As noted above, a period of strained resources in the region could act as a magnet for China’s burgeoning defense industry, albeit not without some complicating factors.

China is likely to offer more attractive financing options than many other exporters. But the quality of its equipment, while improving rapidly, has not yet won widespread embrace among operators who are used to products from the United States, France, and the UK.

Further, China’s model for global infrastructure development has emphasized the use of Chinese labor, as opposed to domestic workforces and companies. In some Middle East countries, this may be acceptable. But in others, it runs counter to both strategic and economic goals that partly drive defense technology imports.

Where much of the Middle East had once been drawn mainly to Western sources for complex defense systems, that is no longer the case. Turkey’s controversial engagement with both China and Russia for air defense systems was perhaps the most visible recent example of this.

But Algeria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and numerous other countries in the region have recently seen fit to source requirements from suppliers outside the usual set of North American or European suppliers. COVID-19 could lead to a quickening of the pace by which the Middle East breaks from historic patterns of defense supply.

Persian Gulf countries will continue to invest

in military hardware, albeit at a slower pace."

Conclusion: Military, Economic and Social Requirements

Another observation made in this white paper series has been that while economic and political fundamentals have been upended by the COVID-19 pandemic, underlying strategic conditions and threat perceptions have really not changed at all.

For many countries in the Middle East, threat perceptions are about as high as they have ever been. This implies that strategy will trump economics when it comes to funding military modernization and readiness.

A critical question is how long it takes for oil prices to return to levels that supported the brisk pace of defense procurement in the region over the past 15 years.

Except for a few difficult exceptions, the greater Middle East region has been less affected by COVID-19 cases than many others. But the global recession and the concurrent collapse in oil prices will not spare the Middle East from a period of economic strain.

At this point, it seems safe to assume that many Persian Gulf countries will continue to invest in military hardware, albeit at a slower pace.

Plans by UAE and Saudi Arabia to expand military facilities in the area of the Horn of Africa could slow down. The same could be true of Turkish presence in Qatar, unless that government is willing to shoulder more of the cost.

Their spending on operations and sustainment activities, however, may be sustained with less disruption, given the underlying social and economic goals these activities can support.

The heavy reliance of some countries in the region on outsiders – foreign companies for technology and operational and sustainment know-how, foreign workforces for a wide array of economic activity – is a variable whose effect is hard to gauge.

In the long term, continued economic stagnation (and low oil prices) could put in jeopardy domestic stability. The experience of many countries across this region over the past decade illustrates the violent consequences that come from a mismatch in economic and political expectations on one hand, and the state’s ability (or willingness) to deliver on the other.