Unmanned Aerial Systems at a Crossroads

Growth and Technology Evolution Depend on Industry Initiative and Investment

The technology development decisions made today are going to determine the future capabilities and utility of unmanned aerial systems.

Given U.S. defense budget uncertainty, it is up to industry to make choices that will either augment or transform UAS for military and commercial applications.

Less than a month after passing a high-profile test of joint manned and unmanned carrier operations, the U.S. Navy and the defense community must suddenly face up to a hard truth: the biggest challenges for the future of America’s unmanned airpower are not only technical, but also bureaucratic.

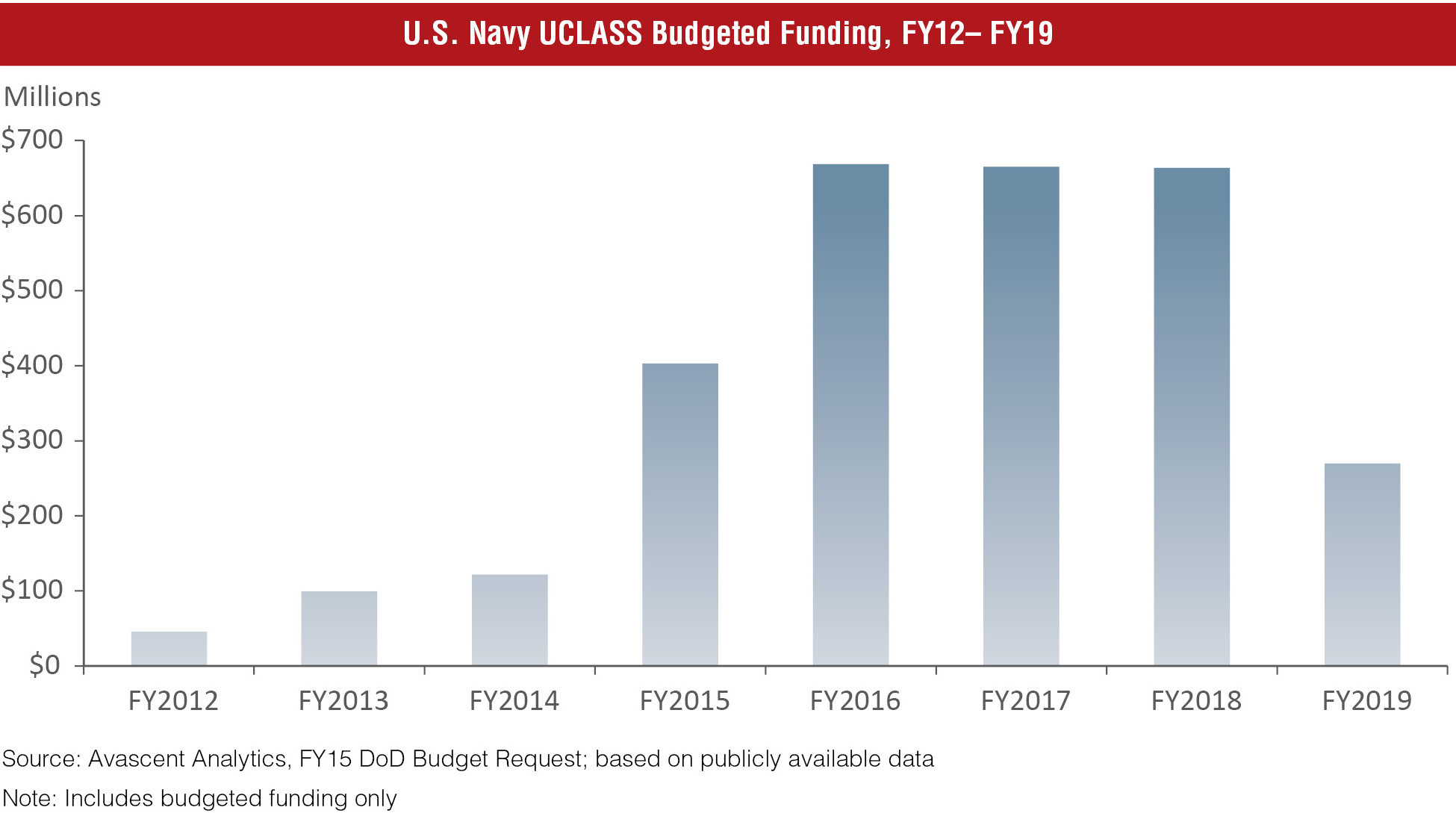

On the eve of what was supposed to be the kickoff of one of the most important contracts in more than a century of naval aviation, history – and the Navy’s new carrier-launched unmanned aircraft – has been put on hold once again. The government’s request for proposal for the UCLASS (Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance & Strike) program is now indefinitely delayed, a product of a tightened budgetary environment, as well as underlying tensions over just how much warfighting capability aviators should cede to their unmanned counterparts.

The delay is significant well beyond the naval aviation community and underscores issues around the evolution of unmanned flight that have major implications for the aerospace & defense industry. Of course, UCLASS is also notable for its budget alone, projected at $1 billion over the next two years. Few new DoD programs have funding that can rival that. More importantly, it is the last major new-start, fully open U.S. military unmanned aerial system (UAS) competition planned for the foreseeable future.

The program’s much debated requirements are a reflection of how far the Navy is willing to push the service’s acceptance of unmanned capabilities, especially if it comes at the expense of legacy priorities around manned aviation. The companies vying for the work also must decide whether to simply bide their time until this delay is resolved or also press on and actively shape the future of unmanned systems in other ways.

The groundwork laid over the next several years will shape whether future UAS will look and operate as they do now, or take on even more functions heretofore performed by manned aircraft.

Unmanned aircraft, popularly known as drones, are at an evolutionary inflection point embodied by this troubled competition. The difficult, existential questions faced by UCLASS decisionmakers ring true for more than just the program alone: Will the next unmanned platforms represent incremental developments that primarily draw upon the demonstrated, capable technology of the past decade? Or is the U.S. on the precipice of an airpower revolution brought about by investment in increasingly advanced but less battlefield tested technology that provides more of the capabilities – i.e., heavier weapons payloads, stealth, and improved propulsion – that increasingly encroach upon the well-defended turf of manned aircraft?

As demonstrated by UCLASS, rapid growth in the unmanned industry and exponentially improving technology is not a fait accompli. The technology development choices that are made today – and how the UCLASS program unfolds – are going to determine the future capabilities and utility of unmanned systems, in military and commercial markets alike. The groundwork laid over the next several years will shape whether future UAS will look and operate as they do now, or take on even more functions heretofore performed by manned aircraft. The prospects for substantial, sustained unmanned growth and expanded usage are real, but it will take the next meaningful leap ahead in technology development to make these things happen. Given the uncertainty surrounding UCLASS, this is a leap that requires new, concerted research and development (R&D) efforts on the part of both government and industry.

UCLASS: Last DoD Program on the Horizon

Since it was first publicly introduced in the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review, the UCLASS platform has been conceived as a critical asset in the Pentagon’s lineup of unmanned platforms. Although UAS were already widely utilized in Iraq and Afghanistan at the time UCLASS was unveiled, Department of Defense (DoD) leadership recognized the benefit of an unmanned platform that would provide, “a longer-range, carrier based aircraft … to provide greater standoff capability, to expand payload and launch options, and to increase naval reach and persistence.” The aircraft was also intended to bolster the Navy’s intelligence-gathering mission at sea, but what would significantly differentiate the UCLASS platform was its ability to take on a combat role, the first time the Navy’s aviators would be joined in that mission by an unmanned aircraft.

Budget realities have since hampered the original vision for UCLASS as laid out in 2006. The Navy must balance operational gains with budget realism – as it stands now, the UCLASS budget is estimated at $1.1 billion from FY14 – FY16. This is about half of what was planned three years ago for this same period, reflecting the new fiscal constraints in which the Navy must plot a course for its future. The ultimate extent to which UCLASS maintains both intelligence and combat missions is also the subject of an ongoing debate in Washington and has again delayed the program by several months. The delay could end up being longer. For now, UCLASS remains a sizeable opportunity: it is the largest new-start unmanned program planned through 2020.

A decision on moving forward with a request for proposal will be put on hold until at least the fall, when the Navy reviews its ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) portfolio during its annual budgeting process. The program’s fate is hanging in the balance, subject to a debate that could mean a fundamental difference in capabilities, if the program gets off the ground at all.

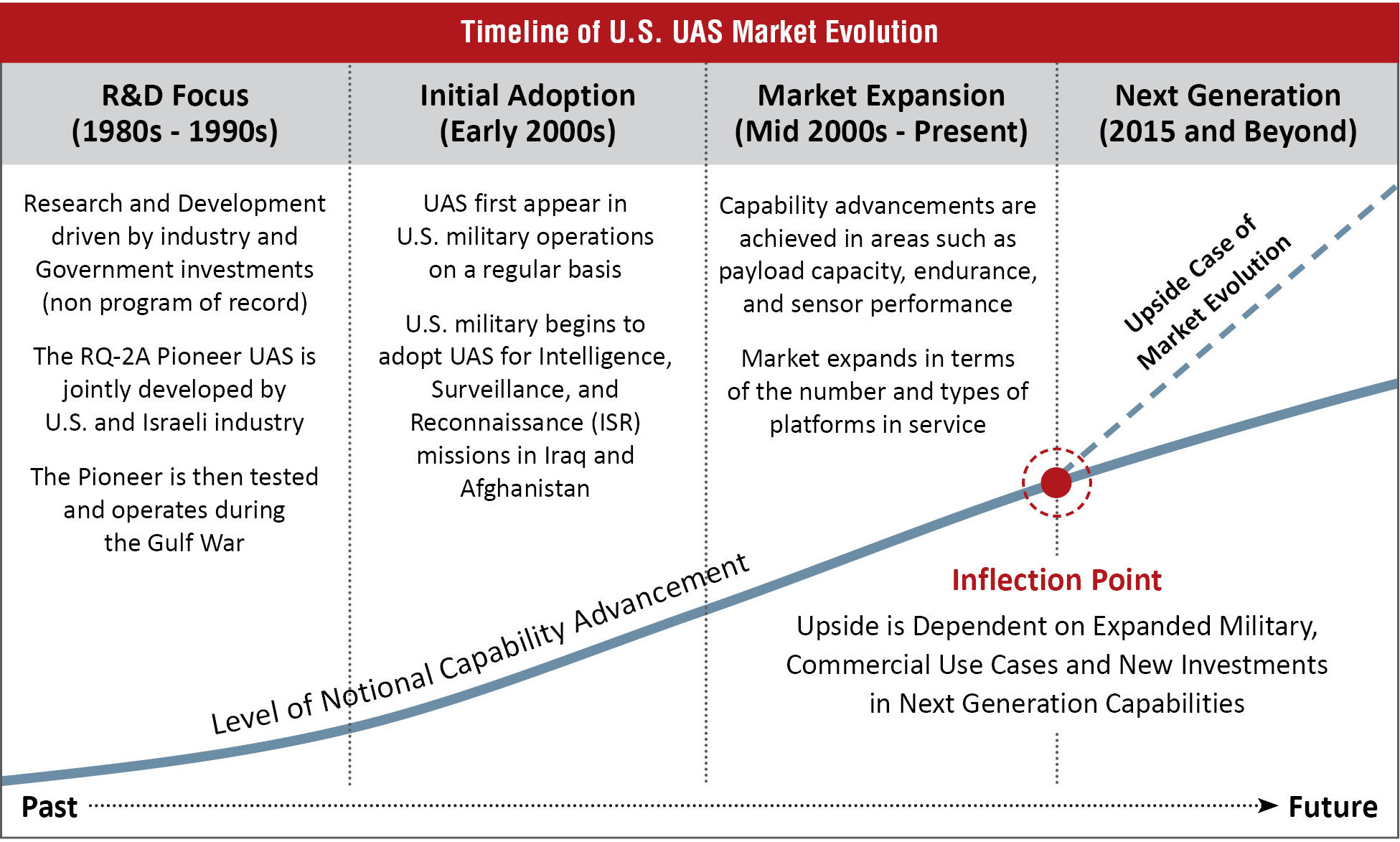

The UAS Crossroads

To fully appreciate the importance of UCLASS – and how it signifies a potential turning point for unmanned systems – it is useful to place the program in historical context. The past decade has seen the ascendancy of UAS as a critical aspect of U.S. military capability. The evolution in technology and breadth of operational activity are impressive, especially considering that UAS were essentially a novelty just 15 years ago. Even in the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom, unmanned systems were hardly a staple of U.S. operations in Afghanistan. Today their constant presence patrolling the skies is a hallmark of U.S. military deployments and intelligence operations worldwide.

While UAS have found uses for missions such as border patrol and counter-narcotics, the surge in customer spending and technology evolution was a product of operational demands of the Middle East and Central Asia. Ubiquitous MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper aircraft have been central to recent U.S. military operations. The carrier-launched UCLASS – with its originally envisioned combat and intelligence mission roles – was intended to push the envelope further than ever before.

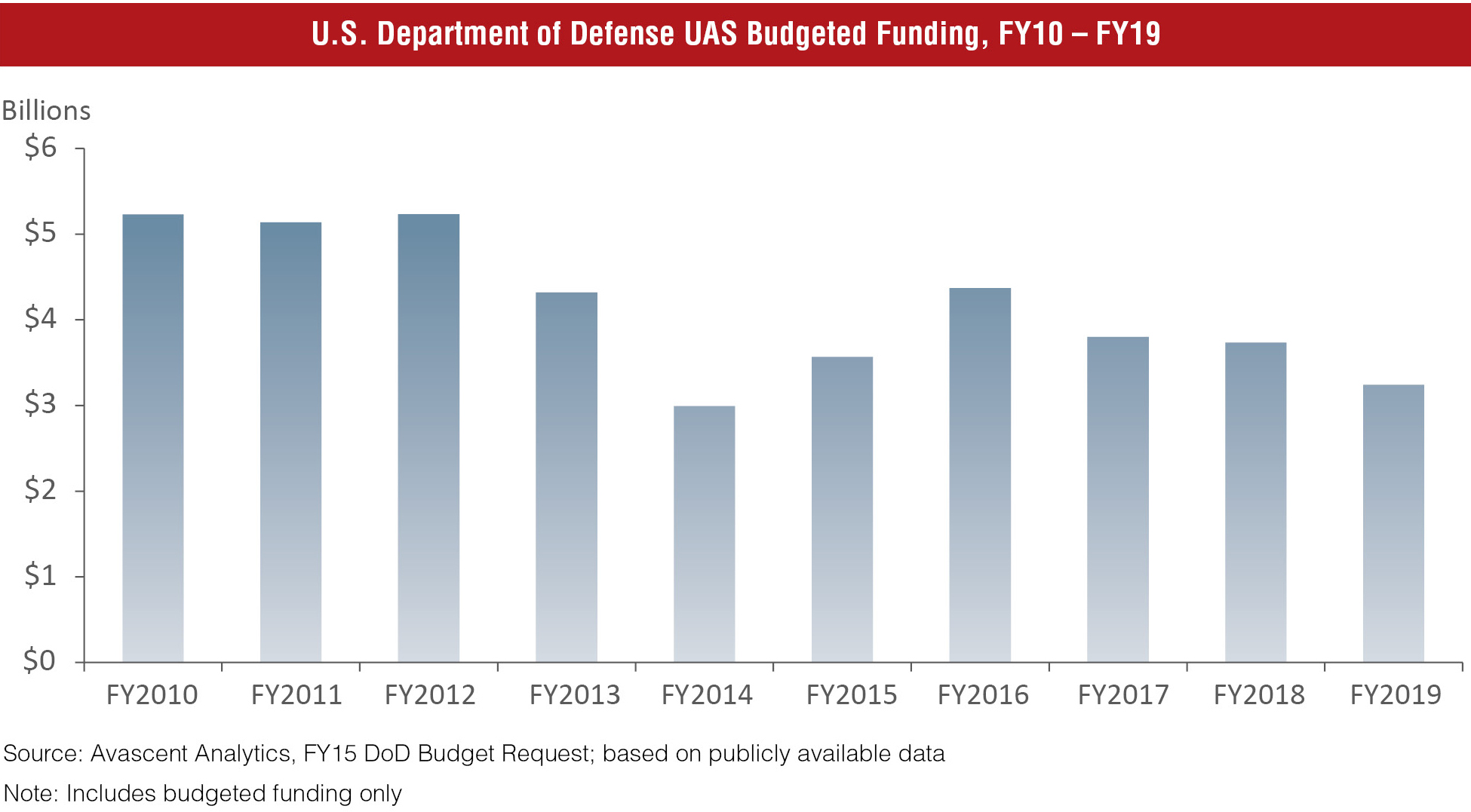

Following withdrawal from Iraq and Afghanistan, discussions within the Pentagon about the roles of UAS and the extent to which UAS funding should be prioritized compared to manned platforms reflect evolving operational requirements and acute budget pressure. While UAS and manned aircraft are often utilized as complementary assets, the reality is that they both can ultimately receive funding from the same sources. The publicly released fiscal-year 2015 DoD budget for UAS stands at about 7% of overall aviation spending. Given the strong constituency for manned aircraft, UAS – with exceptions – are increasingly drawing the short stick on recent Pentagon investment decisions.

As such, the planning for UCLASS and its missions has taken on even greater importance because the future for U.S. military UAS, in general, has become far less certain than the consensus wisdom asserts. To be sure, there are roadmaps that lay out concepts and priorities. But look closely at these roadmaps and there is a clear signal for industry: beyond UCLASS there are no major new funded UAS programs planned by the Pentagon. And even UCLASS has a far more uncertain future than it did just weeks ago. The reality is that – beyond a potentially reworked UCLASS program – near-term, needle-moving funding shifts in the form of new-start development programs are not on the docket. Unless something big happens that is not currently planned (or has been publicly announced), waiting for the next big DoD UAS development program is simply not an option for industry.

This should not be equated with a lack of new funding. Naturally, there will be relatively smallerscale contract awards, perhaps through rapidreaction funding or other mechanisms. New, but smaller, development efforts are likely to emerge, as well as continuing sales of existing platforms. Industry will also see ongoing opportunities to offer bolt-on offerings such as data links or synthetic aperture radars. The Pentagon will continue to be an anchor consumer of unmanned systems and many in industry will find avenues for growth, though not likely ones that resemble major development programs.

In this respect, the environment for unmanned systems is changing. After nearly 15 years of overall spending growth and technology advancement driven by U.S. military operations in the Middle East and Central Asia, the direction of the UCLASS program, if and when it begins, will be a crucial point of reference for the types of demands and expectations that will be placed on tomorrow’s systems.

Given that significant, new U.S. military R&D funding is not on the horizon and UCLASS’ role remains in limbo, it is now up to industry and investors to make a choice about taking greater initiative and actively shaping the future of UAS in conjunction with public sector partners. The extent to which this is recognized will mean the difference between a landscape 10 years from now that looks much like it does today in terms of capability and spending, or one that is fundamentally different.

Future Demand and Evolution Drivers

With this new reality, where do industry and investors go from here, in a post-UCLASS world? To start, examining future drivers offers a guide for how to prioritize investment decisions today. Beyond currently funded U.S. military programs and upgrading existing platforms, there are different but acutely relevant factors that will influence spending growth and capability development, among them: international government adoption, geography, and commercial demand.

Notably, these drivers point towards a new, emerging UAS landscape where the U.S. military has a central customer role, but is no longer the sole engine of growth and technology evolution. They portend a world where UAS increasingly look and operate like manned aircraft – potentially more expensive than the unmanned systems of today, but also more capable. Or, as the UCLASS program could foreshadow, they may not.

These drivers point towards a new, emerging UAS landscape where the U.S. military has a central customer role, but is no longer the sole engine of growth and technology evolution.

International Government Adoption Curve

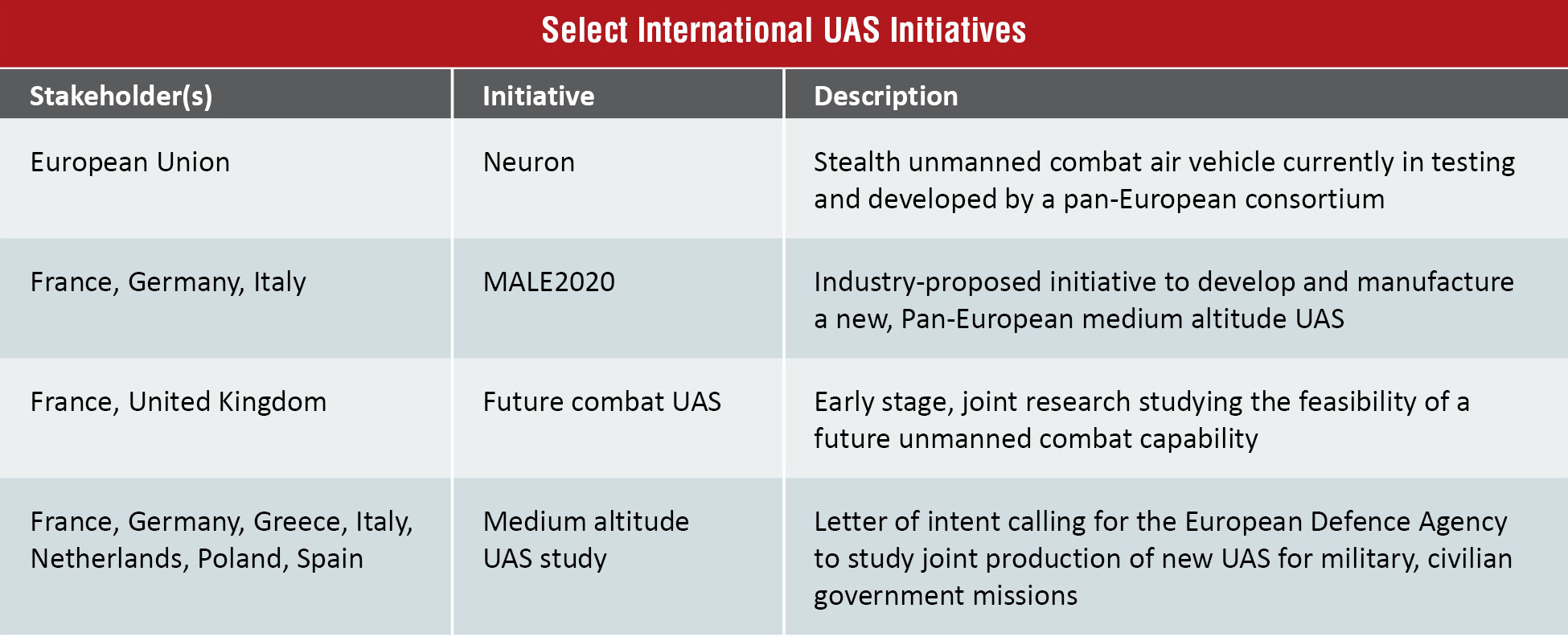

As U.S. military spending on UAS levels off, international militaries and governments are the new frontiers for those looking to grow. With some exceptions, such as Israel, international military funding of major UAS acquisitions has been relatively low to date.

That is slowly starting to change. The current generation of UAS in the U.S. is the next generation for most international buyers, many of whom are seeking to acquire the best American developed capabilities. Throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, countries are investing in increasingly capable platforms. For U.S. industry and others, now is an attractive time to be evaluating international growth potential.

International adoption of unmanned systems is the result of several policy, operational, and industrial factors coming together. U.S. export restrictions on UAS are beginning to loosen to the point that allies and partner nations can often be approved for at least some version of U.S.-produced systems. For many years, potential exports of U.S. military UAS – even to partner countries – were essentially non-starters. Some countries are even funding their own national unmanned programs, as evidenced by the EU-led Neuron program.

International interest is not limited to the U.S. and its military allies alone. China, in particular, has prioritized unmanned systems development, including armed platforms. While precise capabilities are unclear, there are reports that China has utilized unmanned systems to monitor the South China Sea and has converted fighters into UAS. Earlier this year China even signed a deal with Saudi Arabia for UAS sales, a potentially disruptive development for U.S. industry.

Overall, China’s technical expertise in unmanned systems lags Western know-how. Yet given where China was just five years ago with aerospace engineering, it is clear that technical progress is being made, and it may happen faster than observers expected, as was the case with other defense systems. From a military perspective, if the West does not leap ahead in UAS capabilities then it may not be too long before it is asked whether others – especially China – are starting to gain real ground in technology development.

Geography Matters to Military UAS Evolution

For the U.S. military, their area of operations as much as technology drove the incremental adoption of unmanned platforms. In many ways, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the tribal regions of Pakistan are ideal environments for the operation of today’s generation of UAS: controlled airspace, often clear skies, and limited commercial aviation activity. In the future, operators will not always find such favorable conditions. As the U.S. military expands its focus beyond Central Asia and the Middle East, UAS are positioned for growing usage in more congested areas like the Asia-Pacific region. Operational environments with crowded or contested airspace will test UAS technology and operators that have not flown under such conditions. Similarly, the military mission requirements will only grow more complex, particularly in Asia.

Unmanned systems may be required to conduct surveillance and reconnaissance operations in contested airspace; carry heavier weapons payloads; or perform sophisticated electronic warfare or cyber missions. There are no shortage of innovative ways that UAS can increasingly conduct military operations that are too “dull, dirty, or dangerous” for pilots.

From a military perspective, if the West does not leap ahead in UAS capabilities then it may not be too long before it is asked whether others – especially China – are starting to gain real ground in technology development.

Early stage concepts are on the U.S. military’s drawing board, but there has not been a vigorous public discussion about the capabilities and investments necessary to meet future operational demands. Enhanced autonomy and longer endurance are among the capability improvements required for mission success in these new environments. Increasing focus on optionally piloted platforms – ones that can operate with or without a pilot onboard – may also be a way to address evolving mission requirements. Given the possibilities, it is worth considering how Pentagon planners and industry can best engage in a strategic dialogue about the degree to which they are willing and able to shoulder the investments required for the battlefield and geography of tomorrow.

To put it another way, who is going to pay for the future? Unlike most manned aircraft programs, DoD has often expected industry will shoulder a good amount of the development load. This approach can work with development efforts that are relatively low cost but potentially high reward. If that is still the expectation for the next generation – and customers are thinking, “build it and we might come” – then the first step is to find common ground on requirements and costs.

It is a near certainty that future unmanned systems will be used in ways that have not even been conceived of today.

Open Skies, Open Minds to Commercial UAS

Compared to military and even civil government the commercial UAS domain is quite small, albeit one that offers significant upside. The possibilities for commercial UAS abound in industries from oil and gas to agriculture to cargo transportation. Looking ahead, it is a near certainty that future unmanned systems will be used in ways that have not even been conceived of today. Despite the optimism around commercial UAS, actual spending growth has been slow going, and integration with civil airspace will be delayed beyond the FAA’s original estimates. The FAA is still planning to partially open U.S. civil airspace in the near future, but the reality is it will take much longer than that to be fully open to unmanned systems.

From a historical perspective, this delay should not be surprising. To place today’s situation in context, one might draw parallels to the dynamics that existed at the beginning of the jet age when new engines were developed for World War II but eventually found a much larger home in the commercial world. To enable this transition from military to commercial applications, post-war innovation shifted from the government and associated contractors to the commercial sector. Making this transition and laying the groundwork for transformational commercial growth took time and patience. Boeing did not roll out the first U.S. commercial jet – the 707 – until 15 years after the first military jet entered service.

It will take possibly even more time for UAS to make a similar transition. While there has been much discussion around commercial UAS, true adoption is just now underway. Last September, about 100 miles off the coast of Alaska, ConocoPhillips flew the first approved unmanned commercial flight. In June the FAA approved a Puma UAS to survey Alaskan oil fields for BP, the first-ever commercial flight over land. Several local U.S. police departments have also received waivers to operate small UAS.

For this growth trend to continue, it is incumbent upon industry to help make the business case for end users. Industry must clearly convey the topand bottom-line benefits that unmanned systems can provide. The possibilities are limitless. They could include maximizing operational time for an oil rig by monitoring a coming storm or increasing crop yields on farms by detecting nutrition issues and diseases. Civil UAS can help companies save on fuel costs and may ultimately be more environmentally friendly than their manned counterparts. For companies like Google and Facebook, improved sensing from civilian UAS is one more way to enhance the “Internet of things” and transform the way people think about big data. Unmanned systems could also revolutionize how cargo deliveries are made, improving both efficiency and effectiveness.

While the possibilities are intriguing, it is no sure thing that wide commercial adoption will take hold over the next several years. Given technology challenges and the need to ensure safety, the rollout of commercial UAS will be a slow process. The safety record of military UAS has been improving, but there will be no tolerance for error in commercial airspace. The anticipation and potential benefits of civilian UAS are belied by persistent technology issues around navigation, collision avoidance, air traffic control integration, and autonomy. Leaping ahead in the commercial world means ensuring such capabilities are 100% fail-safe.

These challenges are not easy ones to solve, but the U.S. government is making progress through several initiatives. Just last year, the FAA selected six sites across the U.S. for testing specific aspects of integration. The FAA also is planning to fund a new UAS Center of Excellence, which will eventually be a place where industry, government, and academia can share solutions and solve technical problems together. Development and testing efforts are not limited to the FAA alone. NASA, for example, is actively addressing technology challenges through its research initiative (Civil UAS in the National Airspace).

Yet commercial growth will take more than solving technology problems. Civil liberties questions, legal rights, and insurance regulations are critical, hard considerations that still need to be worked out. Economics matter too. If UAS adoption is to grow significantly in commercial sectors such as oil and gas, agriculture, or even air travel, industry must tailor price points and business cases to the unique needs of these customers – not the military. And then there are the issues of training operators, setting up maintenance and repair infrastructures, even identifying where commercial UAS will take off and land; these are not necessarily hard problems, but they will take time to effectively address.

Leap Ahead with New Models for Investment and Development

Even with the uncertainty surrounding UCLASS, there is clear potential for the expansion of unmanned systems. New military, civil government, and commercial use cases can push the UAS industry forward and create an upside scenario of sustained, breakthrough growth.

It is apparent, however, that real challenges stand in the way of realizing this upside. These challenges are not purely technical in nature. High-level advocates in the military and commercial worlds are needed to champion the benefits of UAS. Industry must ensure that decision-makers and the general public can trust UAS in the sky overhead on a daily basis.

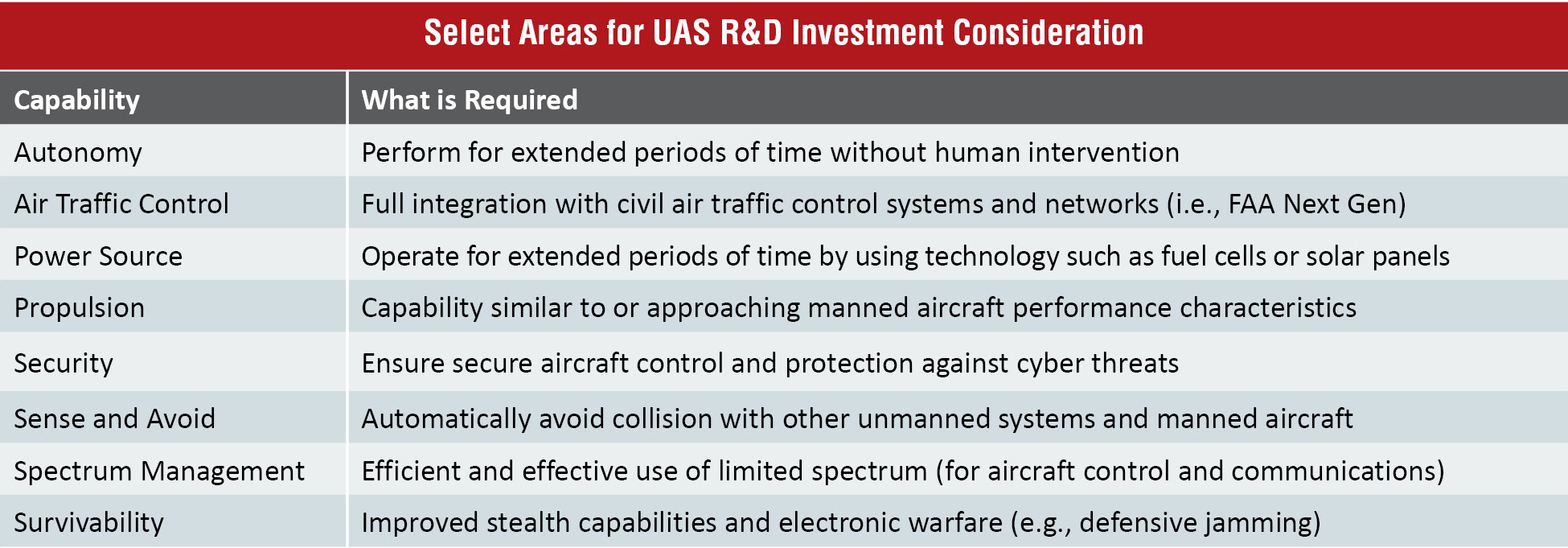

First and foremost, however, technical progress is required for transformational growth in military and commercial domains. This is a “show-me” moment for both the military and civilian UAS industries. It includes developing critical game changing capabilities that, among other things, allow for operations in congested or crowded airspace; safely integrating UAS with civil air traffic control systems; enhance endurance and sustainability; and validate an ever-increasing number of roles and missions.

Traditionally, the defense industry drove such leaps with internal R&D funding or through large-scale government programs. At the crossroads of UAS evolution, both have their shortfalls. Internal R&D investments by corporations alone may not provide sufficient capital to effectively develop the next generation of UAS. Large government funding programs beyond UCLASS are not yet on the horizon, although it is possible that they could emerge at some point in the future. In addition to the traditional avenues of funding UAS development, new models for technology investment also need to be considered.

The future of UAS cannot rest solely on internal R&D or waiting for the next big government-funded program.That simply will not work.

The future of UAS cannot rest solely on internal R&D or waiting for the next big governmentfunded program. That simply will not work. Industry will need to also look toward innovative and disruptive technology development models that maximize internal capabilities while also leveraging the best that public and private sector partners have to offer. This includes UAS technology as well as other capabilities with game changing potential, such as directed energy.

For the UAS industry to thrive, and to stay ahead, it is imperative that the public and private sectors engage in a coordinated effort to make strategic, yet sensible, technology investments that move capabilities forward even if the pace of change is different than government and industry are used to. This implies greater cooperation, as well as smart, targeted investments that in terms of scale that look more like venture funding and less like DoD programs of record – think millions of dollars, not billions. Industry may also consider ways to apply commercial development models to UAS.

These new models carry risks that need to be addressed. Intellectual property rights must be protected and diligence will be required before moving forward with any new partnership or investment. It also is important to comprehensively examine the marketplace, identifying where the best partnership candidates and growth opportunities reside.

This is a new world for many aerospace and defense firms accustomed to making business cases around U.S. government development contracts and formal military acquisition programs. The challenges of innovating and developing next generation UAS technology are high, but so are the rewards. Indeed, UAS are poised to transform military operations once again and even potentially bolster the U.S. economy. Those who lay the groundwork today, will differentiate and position themselves as pioneers of the next chapter of civil and military aviation.

Taking the initiative on UAS offers the prospect of enduring competitive advantage, not to mention the possibility of breakthrough growth. But just how far will industry be willing or able to go? To what extent will government and the military effectively incentivize industry? The answers will shape the unmanned industry’s trajectory and the future of aviation.