Boeing Needs a New Aircraft, But Its Wallet Is Thin

A longtime pillar of American manufacturing, Boeing entered 2021 in the most precarious position in its 105-year history and at a strategic crossroads.

The company faces multiple challenges: the B737 MAX crisis, B787 quality issues and delays, plus weak demand for its newest jet, the B777X.

These events have pushed Boeing into dire straits. After logging 893 net aircraft orders in 2018, the company brought in only 54 in 2019; an unprecedented 1,026 cancellations came during 2020.[1]

And the $4.2 billion deal for Embraer’s commercial business, which would have unlocked regional aircraft opportunities and brought in much-needed engineering talent for a new aircraft design, collapsed soon after Boeing prioritized cash elsewhere.

Boeing is now grappling with a high debt load and negative free cash flow through 2022.

Boeing’s Need to Act

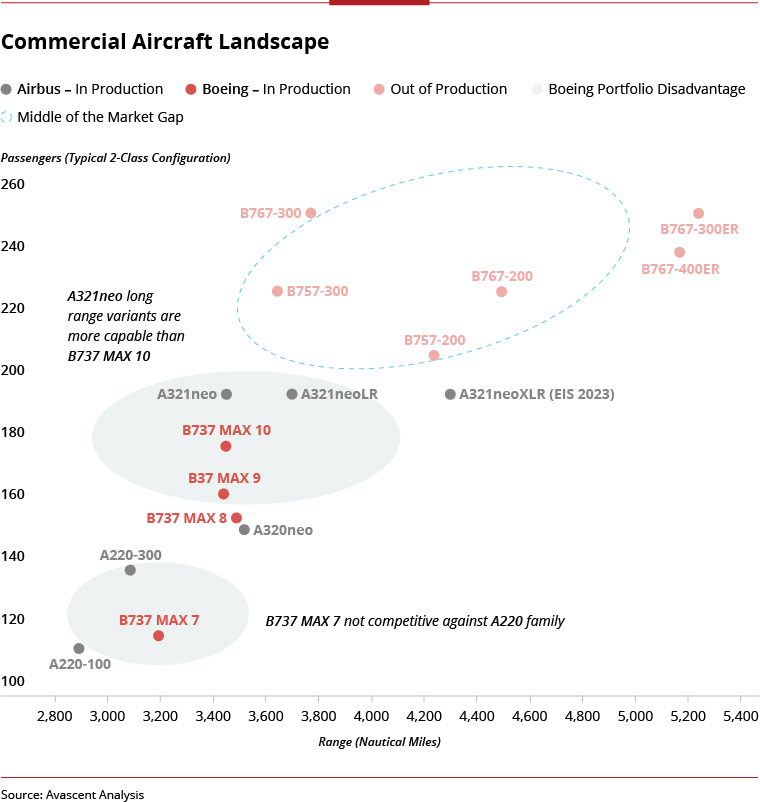

Avascent believes that Boeing cannot afford to focus entirely on the present and must address gaps in its single aisle product portfolio.

Despite soft near-term demand, the company projects a need for 32,270 single-aisle airplanes over the next 20 years. However, Airbus’s A220 and A321neo have eaten into Boeing’s market share in both the low and high-end of the large and profitable single-aisle market.

Sensing its advantage, Airbus is looking to boost A320 family production to 64 per month by Q2 2023, while Boeing projects only 31 B737 MAX per month by the end of 2022.

Avascent believes ceding such a significant portion of the large commercial aircraft market to Airbus is untenable in a duopoly and that Boeing will be forced to act, launching a new aircraft program that is likely aimed at the high-end of single aisle market and low-end of the widebody market.

Such a move could successfully thread a critical needle: no cannibalization of the still popular B737 MAX 8, while concomitantly attacking the A321neo’s position and opening the middle of the market.

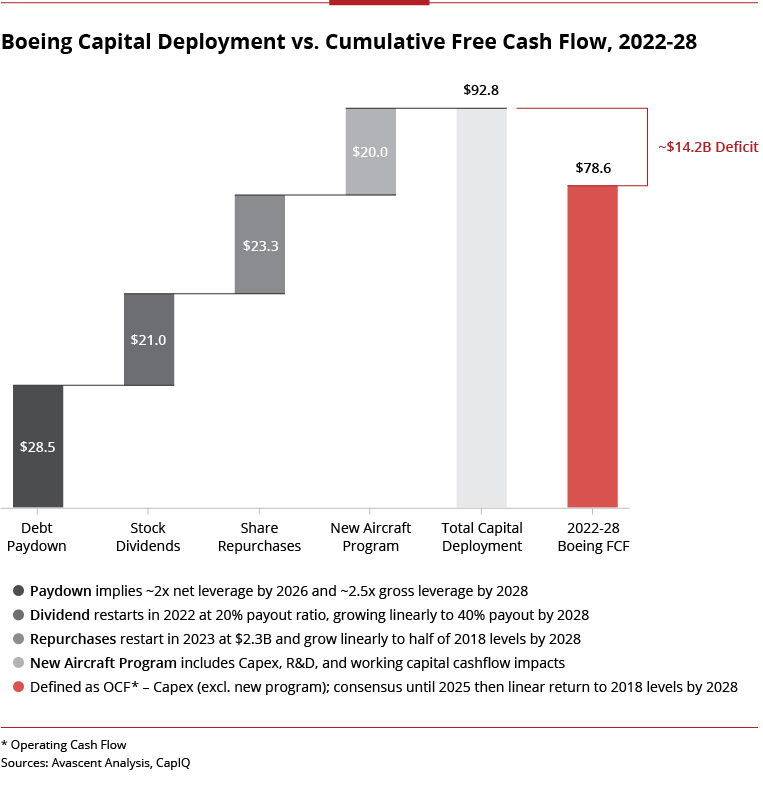

Funding this new aircraft will be a challenge, however. Based on Avascent’s analysis, Boeing likely lacks the cash flow to simultaneously underwrite a clean sheet design this decade and continue to support investor returns via dividends and share repurchases at the levels that shareholders are accustomed to.

As a result, the company may have to consider creative solutions to effectively compete over the coming decades.

Boeing’s CEO Dave Calhoun recently reminded investors that returning capital to shareholders remains a foundational part of the company’s rebuilding. “We want to get back to a dividend policy, and we want to get back to the relationship that we’ve enjoyed with shareowners for many, many, many years,” he said on an April 2021 call with analysts.

Indeed, from 2015 to 2019 Boeing shareholders enjoyed solid returns with shares rising 136% vs. 37% for the S&P500, while the company spent $35.5 billion on share repurchases and $15.9 billion on dividend payouts.

But a closer look at Boeing’s financial condition suggests difficult decisions are looming. Avascent’s $20 billion estimate of new aircraft development costs, including working capital requirements, combined with a return to a modest level of dividends and share repurchases, leaves the company with a $14.2 billion deficit through 2028.

Potential Paths Forward

Should Boeing move forward with a clean sheet program, it will need to either reduce the capital it allocates to shareholders or push down the cost of developing a new aircraft – noting that both will likely be on the table.

In this challenging environment, Boeing will begin considering creative approaches like backing down from its vertical integration plans or cutting research and development funding to rely more on suppliers.

One method for reducing development costs may come through the company’s “Premier Bidder” program, which aims to help the company improve supplier cooperation – although the program’s predecessor, Partnering for Success, developed a reputation for difficult negotiations and tough terms and conditions, which means suppliers may be less than enthusiastic to lock arms with the company.

And after their period of strong financial returns in the 2010s, Boeing’s shareholders are also unlikely to willingly sacrifice their share of the emerging post-COVID-19 recovery.

Faced with these challenging dynamics, Boeing may seek out a partnership with another major industrial manufacturer to fund and execute a new program.

Indeed, Avascent believes the prospect of a “Super OEM” relationship with another multinational conglomerate may be the novel path forward that puts Boeing back on its feet, which Avascent will consider more in-depth in Part 2 of this Altimeter mini-series.

Part Two in the series, Boeing’s “Lost Decade”: The case for a Trans-Pacific Super Tier 1 Partner is available here.

Subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter

We invite you to subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter – Insights delivered to your inbox on critical issues shaping the Commercial Aerospace industry’s future.