Boeing’s “Lost Decade”: The case for a Trans-Pacific Super Tier 1 Partner

In Part 1 of this Altimeter mini-series on Boeing’s future product strategy, Avascent analyzed Boeing’s precarious position as it looks to address critical product portfolio gaps and regain market share from Airbus, all while carefully navigating its high debt load and negative free cash flow.

Avascent has determined that a new aircraft in Boeing’s future would only be feasible if it reduces its typical dividend and stock repurchasing activity and/or significantly cuts development costs for a likely B757 replacement or a next generation single aisle.

And should Boeing instead prioritize a freighter derivative of the B777X, which would require less investment relative to a clean-sheet aircraft, the financial profile remains precarious as long as Boeing continues to divert resources to the B737MAX return, B787 quality issues, and development and certification delays on the B777X passenger variant.

Consequently, it may be well into the latter half of the decade before Boeing can afford the estimated $20-30B+ required for a much-needed clean sheet passenger aircraft, delaying any new passenger aircraft service entry into the mid 2030s.

In every sense, Boeing is short on cash and short on alternatives. But inaction is not an option.

Faced with this delicate balancing act, Avascent believes one of the best ways for Boeing to stave off an otherwise “Lost Decade” is to explore a cost and risk-sharing design and manufacturing alliance with an international, government-supported “national champion” looking to enhance its aerospace pedigree.

Any potential international partner in Boeing’s future will have to have the same sense of urgency and a need for bold action to secure its future. But given its current precarious position, Boeing would have strict selection criteria: first and foremost, strong financial liquidity.

Mature capabilities in advanced aviation manufacturing and a driving interest in promoting indigenous high-skill jobs are similarly important.

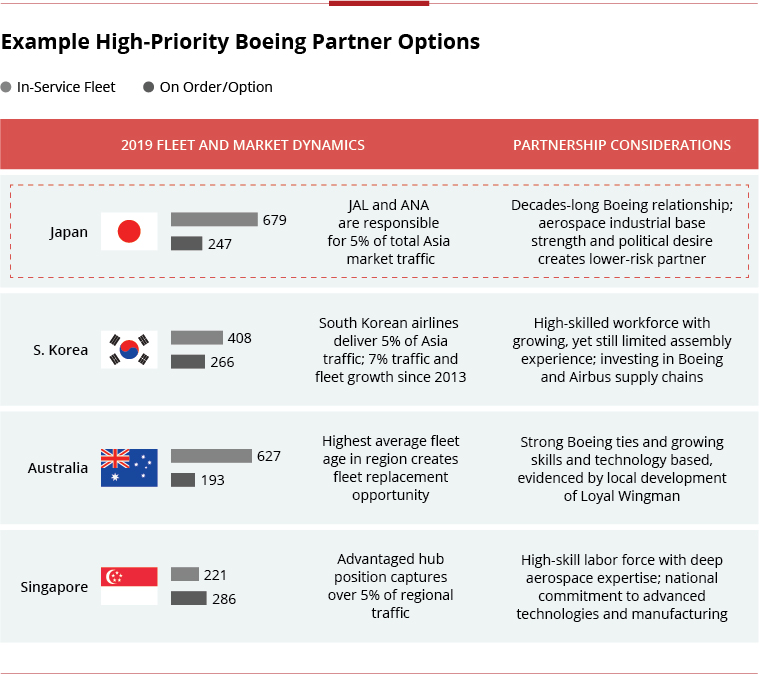

And as tensions between China and the rest of the world intensify, Boeing will have to focus on less polarizing countries that offer a reasonable combination of reliability and assured aircraft demand. This leads to Japan, Korea, Australia, or Singapore.

Japan

Although there are intriguing benefits available in each of these countries, the aggregate benefits of a Boeing-Japan partnership are most compelling and warrant deeper analysis.

The US-Japan relationship is rooted in decades of deeply intertwined economic trade and collaboration, and more recently, a clear political sense of the mutual benefits that can emerge from a closer relationship.

PM Suga and President Biden recently pledged to recommit themselves to an “Indelible Alliance” that includes closer industrial cooperation in developing cutting-edge technologies. More than any other time in the post-war era, shifting geo-politics and global economics are drawing the US and Japan together.

There is precedent for closer commercial aerospace cooperation. The origin of Boeing’s existing strong relationship with Japanese industry began in the early 1970s, set against an existential crisis much like the one Boeing faces today.

Cash-poor following the launch of the B747, Boeing courted a Japanese consortium to help launch a midsized aircraft that would counter the threat of a new competitor’s midsized aircraft: the Airbus A300.

Boeing’s B767 eventually provided Japan with an opportunity to carve out its first legitimate role in the global aerospace supply chain, and its subsequent workshare growth on successive B777 and B787 programs has delivered important credibility for the Japanese aerospace industrial base.

![]()

“They [Mitsubishi, Kawasaki and Subaru] are incredibly competent, important players in the industry who, if they want to — and if they believe they’ve got some innovative capabilities — [could] move into more of our kind of world…I’m open to any major partnership.”

– Dave Calhoun, Boeing CEO (May 2020)

Yet the Government of Japan (GoJ), and especially MHI, has long sought a more prominent, indigenous OEM role. To this end, three separate Boeing-Japan JV attempts over the past five decades have been proposed, but each failed due to unforeseen market forces or political reasons.

Ensuing Japanese frustrations eventually became the impetus for the now-failed SpaceJet program (formerly MRJ), which was finally “paused” in September 2020 after years of delays and billions of dollars in losses.[1]

Despite the bitter experience of SpaceJet, the Government of Japan is keen to keep its commercial aerospace industrial base healthy and growing. Hence, the dreams of a Japanese OEM live on, but in a wiser and more sustainable way, and perhaps with a willingness to accept something less than a full OEM status.

To that end, a Japanese consortium relationship with Boeing could lead to a co-funded, co-produced new generation passenger aircraft. Importantly, this differs from how Boeing evaluated the Embraer joint venture, where Boeing’s interest in Brazilian engineering talent outweighed any strong need for co-funding.

The demise of SpaceJet actually makes MHI, or a consortium of “Japanese Heavies,” a more attractive industrial partner for Boeing’s future, as MHI will now be less distracted and more liquid. An MHI-led consortium, potentially including KHI, Subaru, and perhaps some capable Tier 2 companies like Shin Maywa or Toray, would be a credible collective force.

They may not have the design experience of an Embraer, but they have decades of experience on major Boeing work packages, including co-design responsibilities on the B767, B777, B787, and B777X.

There is no chance that this approach would create a competitor for Boeing, just a more capable and useful set of partners.

In addition, MHI and its partners would bring forward many lessons learned from SpaceJet, where regulatory and certification missteps were more of a factor than engineering shortcomings.

Most importantly, Japan’ offers a highly capable work force with advanced manufacturing skills, many of which have been optimized in the automotive sector and could play a key role in Boeing’s future. Although this world-class Japanese labor is expensive, it is no more expensive than that of the EU, Canada, or the US.

Boeing has long seen the potential in these capabilities, and it is no secret it wants to harness these kinds of skills to deliver a future lower-cost, high-volume production aircraft. As the saying goes, “you get what you pay for,” and the 787 program offers some hard lessons in how not to cut costs.

Given Japanese industry’s risk aversion, there is much that the Government of Japan can do to facilitate and nurture a “Super Tier 1” consortium that would be a more equal partner in the development of a new passenger aircraft, while remaining well within WTO regulations and guidelines.

A new JAXA-led effort called the “Aircraft DX Consortium” appears capable of providing a strong foundation for this new “Super Tier 1” ambition and would importantly help Japanese industry become more confident to share technical and financial risk with Boeing.

Boeing’s Future Path Forward

For Boeing to successfully cultivate a new strategic alliance with Japanese industry – or any other viable international partner listed above, a three-prong approach is required.

First, Boeing should coordinate a collective USG outreach to Japan and convince Congress, the White House, the Department of Commerce, and the Department of State of the merits of this initiative.

Boeing must then directly approach the Japanese Government to better understand their motivations and offer sufficient participatory incentive to drive political and public support.

Finally, Boeing must convince potential Japanese coalition partners that this new arrangement will fare better than historical attempts, and that the offered workshare will meaningfully contribute to helping Japan realize its dreams of commercial aviation prominence.

To be clear, Boeing needs Japan, and Japan needs Boeing. Japan can be a financial and risk sharing partner that would allow Boeing to launch a clean sheet passenger aircraft and avoid a “Lost Decade.”

Meanwhile, Boeing can help rejuvenate a stagnant Japanese commercial aerospace industrial base and help promote new cutting-edge manufacturing technologies and processes, and most importantly, jobs. Executed properly, with the full engagement of both the US and Japanese governments, Boeing can:

- Reinvigorate a valuable long-term partner,

- Launch the new passenger aircraft it desperately needs, and

- Chart a bold path for its future.

Subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter

We invite you to subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter – Insights delivered to your inbox on critical issues shaping the Commercial Aerospace industry’s future.