Regional Aircraft Market Cycles – Time for an Upswing?

![]()

“We’re struggling with [how to serve small cities]; we feel some obligation to keep the communities connected, but the economics ultimately aren’t going to work, and pilot shortages – you know, they’re getting squeezed…As the economics of 50-seaters are changing so radically, it calls into question what the answer is. And we don’t have the answer yet.”

– Scott Kirby, United Airlines CEO (July 2021)

“If we are still flying the same fleet in ten years, we are going to be in trouble."

– Chip Childs, SkyWest (September 2021)

Twenty years ago, 13 different regional aircraft types spanning 19 to 78 seats were in active production by eight OEMs, contributing to record-setting annual delivery figures and order backlogs.

Yet today, only five regional aircraft are still in production across two manufacturers:

- Three variants of Embraer regional jets (RJ) and

- Two turboprops from ATR.

They are the last left standing amidst a particularly fraught last three years, highlighted by:

- June 2019: Bombardier’s divestment of its CRJ program to new competitor Mitsubishi;

- November 2020: Mitsubishi ceasing development of the SpaceJet, which had been poised to fill the gap left by the terminated CRJ program;

- February 2021: De Havilland Aircraft of Canada “pausing” (but likely terminating) production of the Dash 8-400 turboprop, another recently divested Bombardier program; and,

- September 2021: AVIC’s Xian MA700 Chinese turboprop losing access to its Pratt & Whitney Canada PW150 engine amidst geopolitical tensions, all but ending a program that intended to satisfy growing demand within China and other emerging regions.

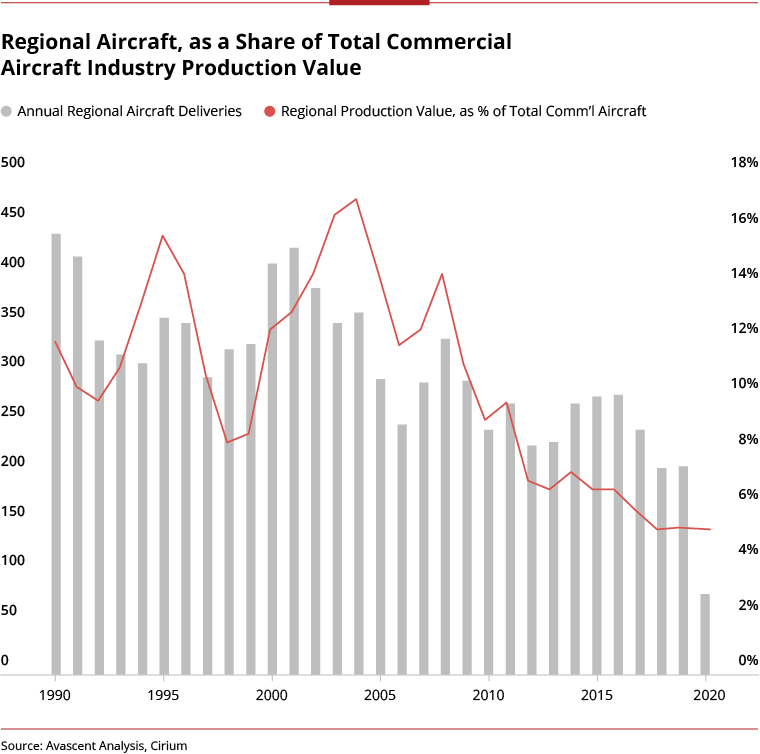

For many aerospace suppliers, these exits seem like a fitting coda for the regional aircraft market that had become a frustrating afterthought. By 2017, regional aircraft had come to represent just 5% of the commercial aircraft industry’s total value, down from 16% in the early 2000s “glory days.”

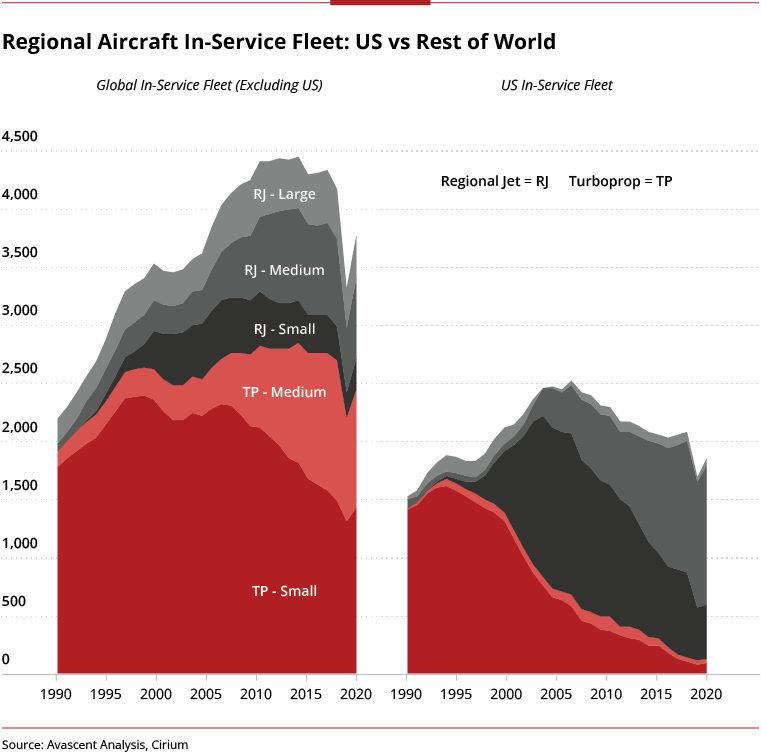

Yet despite the current malaise, the regional aircraft market is poised for a revival with far-reaching implications. The “glory days” of twenty years ago have left approximately 5,000 aircraft, or 2/3 of the current fleet, facing retirement in the next 15 years.

In addition to this replacement opportunity, incremental growth in regional air travel is expected as economic liberalization in emerging countries continues and as new post-COVID behavioral shifts appear poised to become more ingrained. This includes:

- Business Travel: Demand for more short-haul flights to serve business travelers that are embracing permanent virtual work in non-urban homes, as evidenced by a twofold increase in the net flow of people outside of US urban areas after March 2020[1];

- Leisure Travel: Continued prioritization of domestic leisure travel (which is back at ~90% of pre-COVID levels as of July 2021) relative to international travel (at ~25% of pre-crisis levels), due to public health and border control considerations[2]; and,

- Sustainability Concerns: Industry-wide interest in placing sustainability at the forefront of the COVID-19 recovery, which will necessitate the adoption of more fuel-efficient, low or zero-emission aircraft.

In recognition of these dynamics and today’s limited competitive field, numerous disruptive companies are investing in new technologies to challenge the incumbents, carve out a role in the future regional aircraft market, and help drive a broader, long-term overhaul of the commercial aviation ecosystem.

We will assess the evolving competitive landscape in the second part of this series on regional aviation. But to fully understand the demand profile ahead, a brief review of the regional aircraft market’s historical trajectory is warranted through the lens of airlines’ two largest operating expenses – fuel and pilot labor.

The way in which these issues shaped prior fleet decisions will resemble the way they impact the next major round of fleet decisions ahead.

Regional Aircraft Market Drivers

For the largest mainline carriers in the US, fuel and labor have accounted for 18% and 40%, respectively, of total operating expenses since 2015.[3]

But their impact is particularly acute when spread across fewer seats on small regional aircraft.

US airlines’ management of these cost items has been particularly impactful, since US operators generated 60% of regional jet demand during the market’s production peak between 1995-2004.[4]

Fuel

As fuel prices have climbed over the decades, larger gauge regional aircraft have been increasingly necessary to reduce seat-mile costs.

The first regional upgauge wave began in the late 1990s. 20- to 40-seat aircraft, which had first established modern regional route networks for major airlines, were overtaken by a surge of orders for faster and longer-range 50-seat aircraft.

By the mid-2000s, however, the second transition was underway, as 70+ seat aircraft with lower seat-mile costs and a premium cabin were used to counter emerging competition from low-cost carriers running larger narrowbodies on underserved point-to-point routes.

As fuel prices remain stubbornly high, the calculus to keep upgauging with inefficient RJs has become more challenging. Many global carriers have turned to large turboprops to reduce operating costs, but these aircraft have struggled to take hold in the US.

Public perception appears to play a role in this, as prior marketing campaigns to support airlines’ RJ orders seem to have wrongly convinced the public that a turboprop was an inferior, less safe product.

Yet faced with an aging fleet and no clear “right sized” replacement option, US airlines may soon have to reexamine their avoidance of turboprops or otherwise continue to cut routes.

In June 2021, United Airlines perfectly exemplified this balance act by simultaneously placing orders for new B737s to upgauge many existing regional routes, cutting numerous regional destinations, yet also making an initial commitment for 19-seat electric turboprop aircraft that will be delivered by new OEM Heart Aerospace in 2026.

Labor

Upgauging has also become more challenging due to pilot labor agreements.

Major US airlines’ contracts with pilot unions include “scope clauses” that limit outsourcing of regional flying to low-cost third party airlines; this includes barring regional airlines from flying aircraft over 76 seats or 86,000 lbs MTOW[5]. The number of sub-76 seat aircraft allowed in the fleet is also capped, often in proportion to the mainline carrier’s overall fleet size.

Despite a brief period of pilot overcapacity at the beginning of COVID-19, the industry has been barreling toward a serious pilot shortage over the last decade that has only exacerbated the scope clause standoff.

As regional pilots are increasingly lured to higher wage roles to fill the emptying cockpits at larger airlines, regional carriers have had to reduce operations, or in some cases, file for bankruptcy.

This phenomenon was already beginning pre-COVID, exemplified by the bankruptcy of major US regional carrier Republic Airlines in 2017, but has been further accentuated amidst the pandemic (e.g., Delta and American Airlines partners Compass Airlines and Trans States Airlines; British regional carrier Flybe; AirAsia’s subsidiary AirAsia Japan, etc.).

On the Cusp of a New Regional Aircraft Market

The interplay of these fuel and labor challenges – especially in the heavily influential US market – effectively paralyzed much of the regional aircraft manufacturing industry over the last decade.

Amidst an increasingly competitive environment at many smaller airports, the inefficiencies of smaller jets combined with the limited use of larger jets compressed the addressable customer base and made it even more difficult for aircraft OEMs to close a business case for new regional aircraft programs.

The devastating financial blow from COVID-19 has left the regional aircraft market in an unrecognizable state, but customer demand signals are returning and new industry tailwinds are forming – with the most compelling being the role for regional aircraft in the aviation industry’s decarbonization movement.

In Part 2 of this analysis, we will:

- Explore the new demand drivers and their intersection with airlines’ fuel and labor considerations;

- Assess the newly forming competitive field that seeks to disrupt the remaining incumbents; and

- Discuss the strategic implications for the OEM and supplier landscape.

Subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter

We invite you to subscribe to the Avascent Altimeter – Insights delivered to your inbox on critical issues shaping the Commercial Aerospace industry’s future.